Historic buildings are the only works of art we feel the license to neglect and destroy. A sane person would never swing a hammer at a Rodin sculpture or slash a Picasso, even if such artworks offended them. But a schoolhouse made in that same era somehow stood in the way of progress.

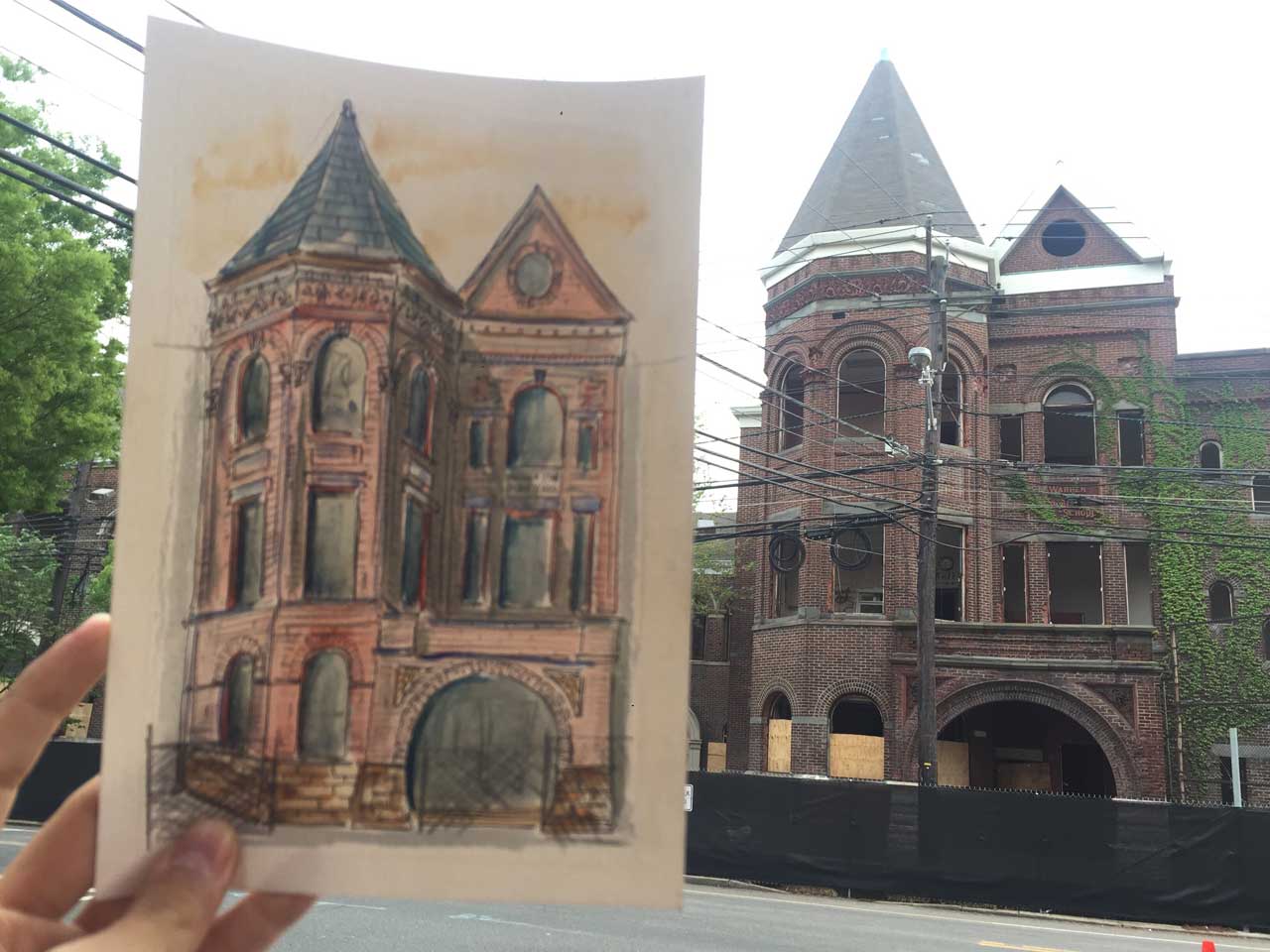

Built in 1908, Warren Street School in Newark’s University Heights was a work of art — that was the opinion of the State Historic Preservation Office (SHPO) long before NJIT demolished it last week. Not even the facade will be spared — with its romantic resemblance to a medieval castle — nor the Louis Sullivan-style floral adornments hand-carved by Italian smiths.

Days after the demolition began, came a timely bookend. James Street Commons Historic District, whose residents had fought to save the nearby school for over a decade, was named one of the most endangered places in the state.

“Preservation New Jersey charges institutions and developers to think more deeply about ways their new projects can respect the boundaries and corresponding scale and stylistic guidelines of the James Street Commons Historic District,” said Emily Manz, Executive Director of the non-profit organization that decides the annual list of ten endangered places.

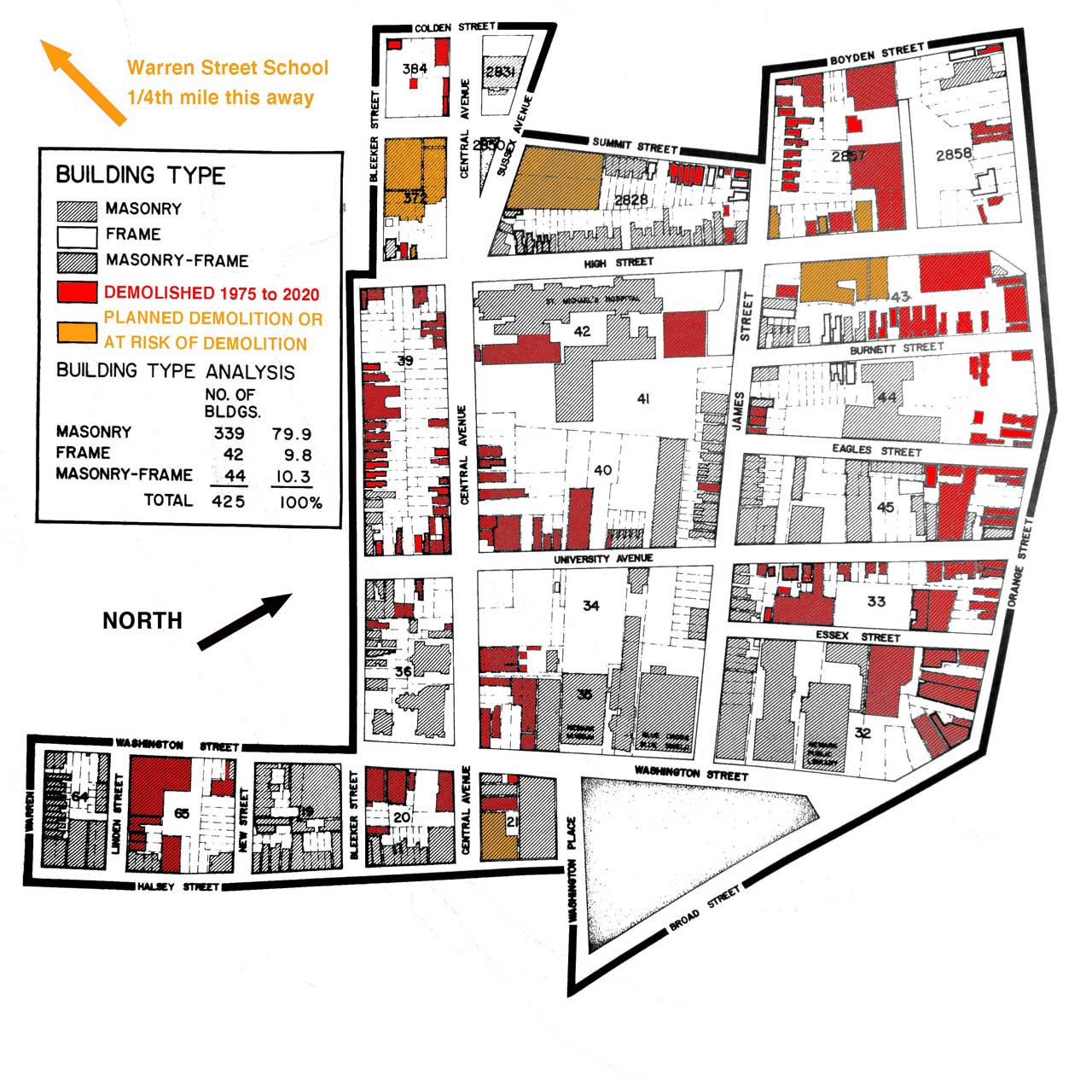

This announcement has been five decades in the making. Year after year, a row house here and a brownstone there disappear. Since 1975, nearly half of the buildings within the 24-block historic district have been torn down.

Sometimes these structures were brought down by a private developer who promised otherwise. That was the case of the Lloyd Houses in the late 80s. Sometimes landmarks were turned into rubble by long-standing institutions who strung the community along.

Given the history of the city, and the exodus after the Newark Riots, criticizing an anchor institution like NJIT for its campus expansion is often construed as ingratitude or nimbyism. The university, which generates 5,000 jobs for the city, has many vocal defenders — some are readers of this publication. Other defenses come from higher-ups.

“NJIT has had a strong commitment to historic preservation, particularly when programmatically and economically feasible,” said Matthew Golden, Chief Strategy Officer, who noted the adaptive reuse of the fire-stricken school was too costly. “There are no other historically significant buildings on our campus slated for demolition.”

To be fair, NJIT has restored important historic buildings on campus at great cost — namely its flagship building known as Eberhardt Hall and the Central King Building. A 19th-century townhouse at 321 Martin Luther King Boulevard is currently undergoing renovation. In 2007, NJIT published a master plan that envisioned the 19th-century townhouses on the 200 block of the boulevard becoming a “Samson Row,” inspired by the famous street in Philadelphia. These are wonderful things on paper. But the Warren Street School demolition — and the tiptoeing around with which it was carried out — has put the community on edge.

NJIT has a trove of properties in and around the historic district with no clear timeline to use them or renovate them. This practice is known as land banking, which activists find improper for a tax-exempt institution to engage in.

“That’s not what a taxpayer-sponsored institution should do,” said Zemin Zhang, Executive Director of Newark Landmarks.

Zhang, a James Street resident, prepared the nomination last year for Preservation New Jersey in which he pointed out 12 landmarks in the neighborhood facing demolition. Since then, four of those landmarks have been demolished by NJIT, including Warren Street School. The pace at which the neighborhood is vanishing is only accelerating, according to the James Street Commons Neighborhood Association.

“NJIT has a vice president of real estate development. This is kind of strange, isn’t it?” Zhang said, referring to the title of one of the administrators. “If you use a real-estate mentality, you will treat the city and your own assets very differently.”

The problem appears to be citywide. Newark is a city with an extraordinary history, where suffragettes and activists brainstormed in row houses on Halsey Street. German brewers built kingly monuments. A civil rights activist, the father of a future mayor, was incarcerated in one of the oldest jails in the nation now crumbling and piled up with squatter garbage. These places — all works of art — are at risk of demolition.

As a giant metal claw ripped apart Warren Street School, Myles Zhang, Zemin’s son and an architectural historian, said he overheard the construction crew talking among themselves. “Those historians want to keep these old bricks,” they said. “You can’t tell the difference anyway.”

It’s true — some people can’t tell the difference. Others can. And when works of art are destroyed, we mourn them, as well as a world that sees so little value in them.

“When I first noticed the demolition of Warren Street, I was debating whether to let it pass or to make some noise,” Myles wrote to me.

Growing up on James Street, Myles has witnessed so much demolition in his life — places like the Polhemus House and the Westinghouse factories — that he dedicated his life to studying architecture. Spending time with family before beginning a doctoral program in Ann Arbor, he had come home in time to see the demolition of the schoolhouse. He spent an afternoon drawing the school as a memorial, then picking through the rubble of priceless ornaments — eulogizing both the building, as well as the decade-long fight to save it.

Another fight has been lost. But there are more endangered landmarks to save, such as the Colonial-era residences in Camden County, African-American churches in Cape May and Trenton, and other places recognized by Preservation New Jersey.

“Someone in power was counting on us to be silent. That was when I realized demolitions like this matter because they set a precedent for what state institutions and the city can get away with,” Myles continued. “Other monuments that we cherish more than Warren Street School could meet this fate, too.”