Statues of colonizers, slaveholders, and segregationists are falling at the hands of anti-racism protesters who believe that these monuments are pillars to white supremacy.

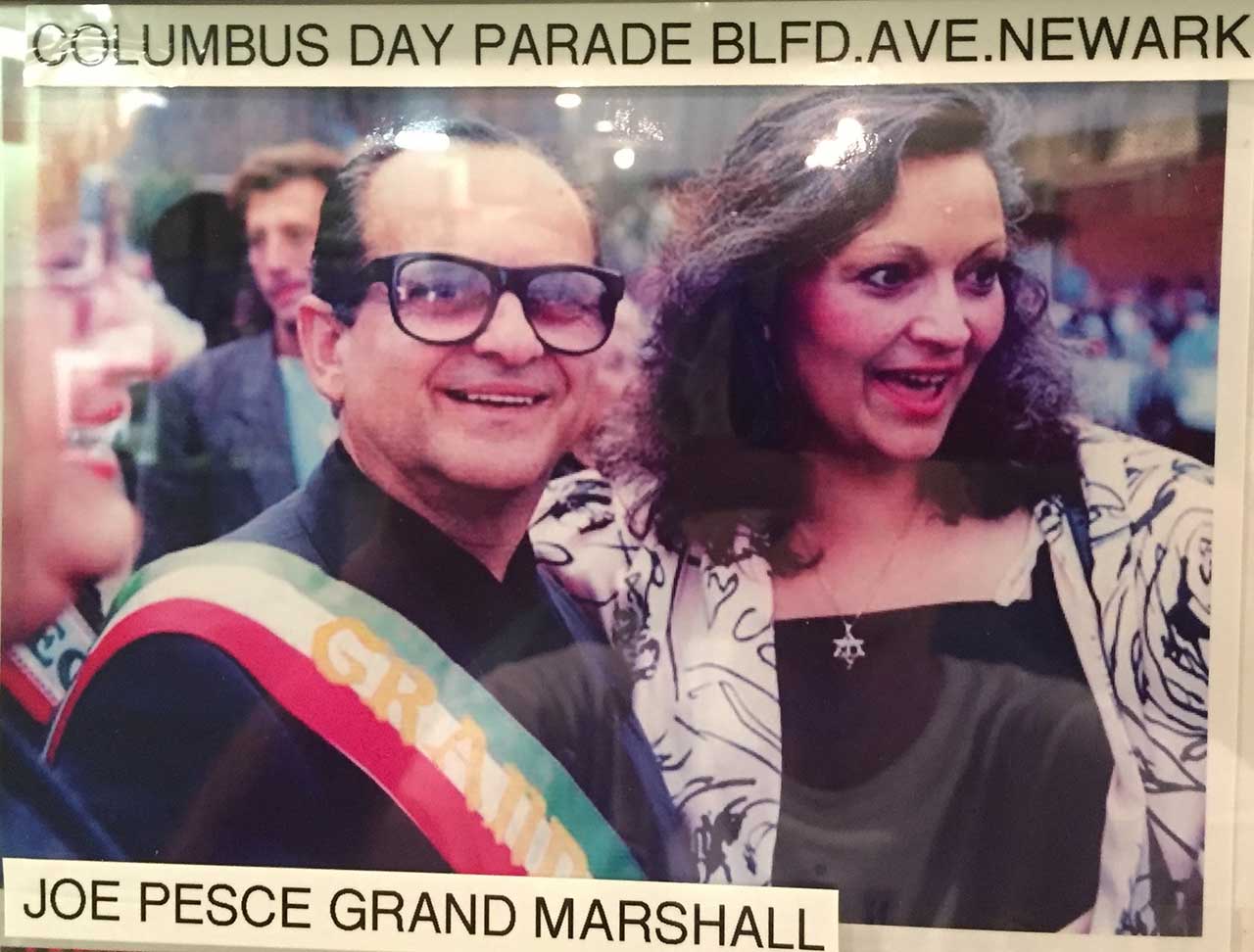

In Newark, onlookers in the dark hours of the morning, watched a century-old statue of Christopher Columbus removed from a plinth at the mayor’s orders. The city’s last statue of Columbus is still standing in the North Ward, but many believe it is only a matter of time before the 15th-century explorer tastes the waters of the Passaic River.

The “vandalism” of the statue has outraged Italian-Americans, who see Columbus as a symbol of their heritage. “There should have been a public hearing on the matter where both sides of the issue could be understood and an alternate solution to the problem worked out,” said Michael Calabro, vice president of the Newark-based Columbian Foundation.

Others believe it is time to finally disassociate from the man blamed for the Taíno genocide. In fact, there is nothing ancestral about celebrating the so-called immortal Genoese. Columbus, who was from northern Italy (the “good” Italians), was already part of American mythology when the southern Italians (the “bad” Italians) arrived. The new immigrants, who were considered second-class citizens and were the subject of immigration quotas, latched on to Columbus as a way to defend their legitimacy.

“Italians needed Columbus a century ago, they don’t need him now,” said historian Michael Immerso, author of Newark’s Little Italy. “For us to defend our historical identity by choosing someone from Genoa, historically makes no sense.”

The idea for Newark’s first Columbus statue came from a member of the Giuseppe Verdi Society around the time when the federal government had passed a harsh immigration law, restricting the entry of Italians. On the day it was unveiled in Washington Park in 1927, a telegram from Mussolini was read to the crowd, followed by a parade of thousands.

If Italian-Americans were to replace Columbus with a less controversial paisano, they would not be hard-pressed to find someone suitable. Along the walls at the Museum of the Old First Ward, for instance, are hundreds of photos of people who left behind legacies to the city. Most beloved was Mother Cabrini, who in the 19th century opened orphanages, hospitals, and schools, including one in the Ironbound. It is impossible to say an unkind word about her. And yet, when it comes to the thought of her replacing Columbus, Italian-Americans from Newark plant their flag in the ground.

“History is not negotiable. Culture is not negotiable,” said Bob Cascella, the museum’s curator. “People’s ideas about their lives and background are not negotiable.”

Schoolchildren in the United States learn about Columbus through nursery rhymes and storybooks. The emotions we feel toward these types of patriarchal figures are complicated because they are bound up in our earliest memories. Learning unpleasant truths about them — particularly the harm they caused others — can feel like something sacred is being desecrated.

And in most places where controversial statues are toppled, there are other cultural artifacts for people to have pride in. In Newark, few relics remain.

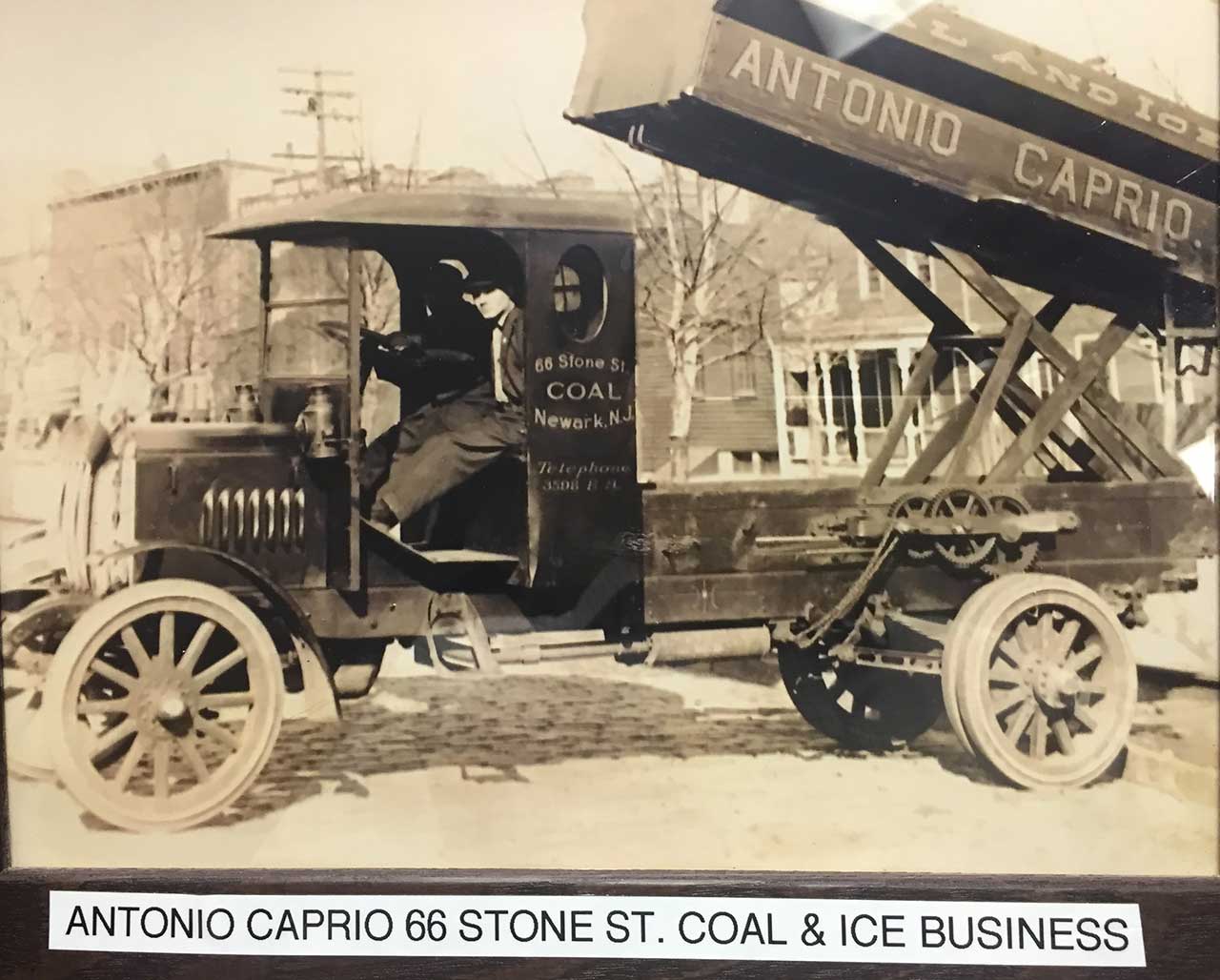

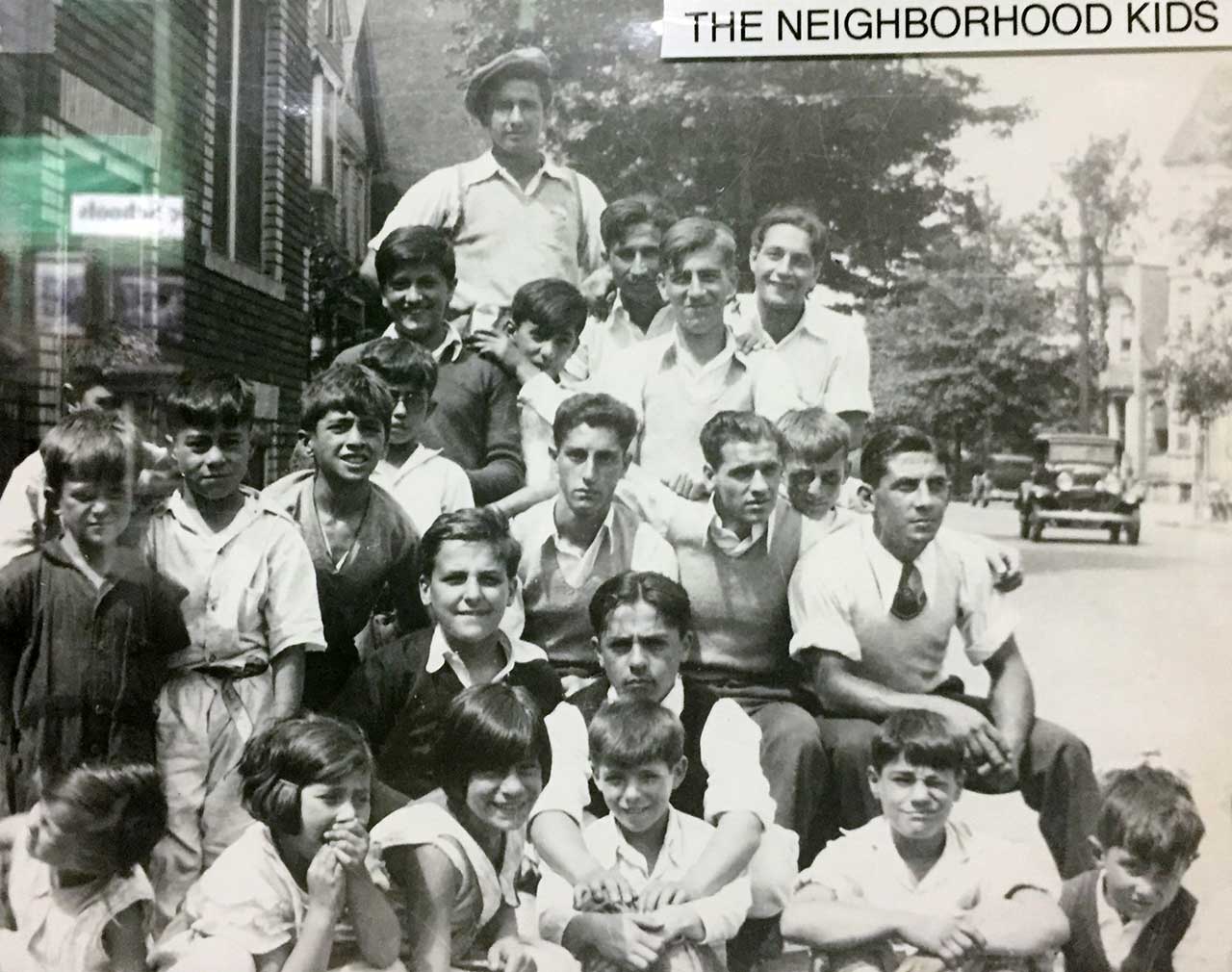

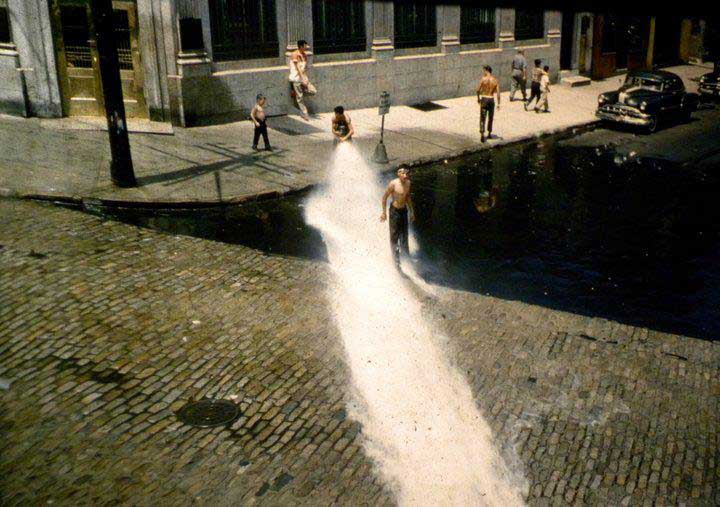

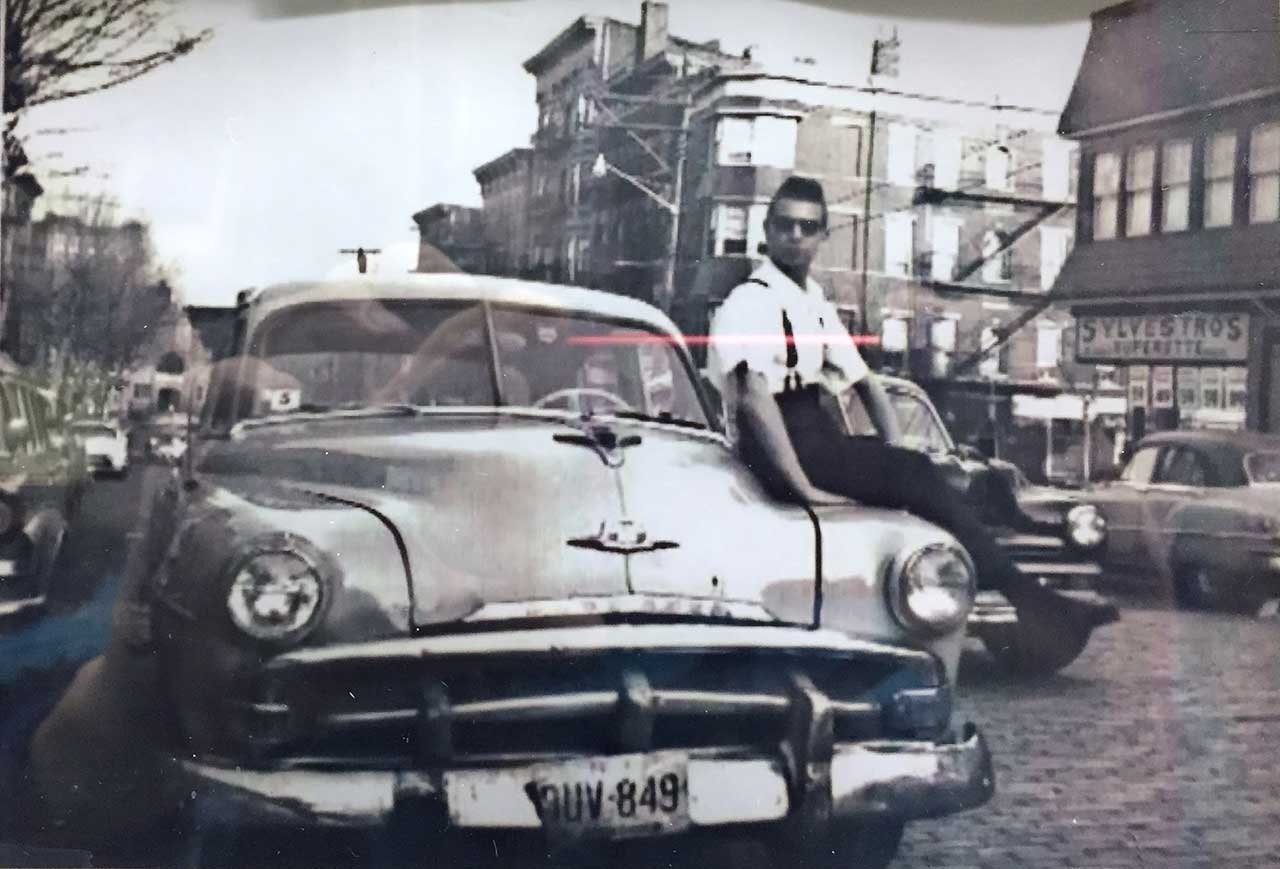

Italians arrived in Newark at the end of the 19th century as railroad workers and day laborers. They passed down stories of hardship, ones that are not dissimilar to what black communities report today: harassment by police, redlining, and being depicted in the media as violent. Back then, newspapers openly described Italians as “swarthy,” “dirty,” and unable to conform to the culture of the new land.

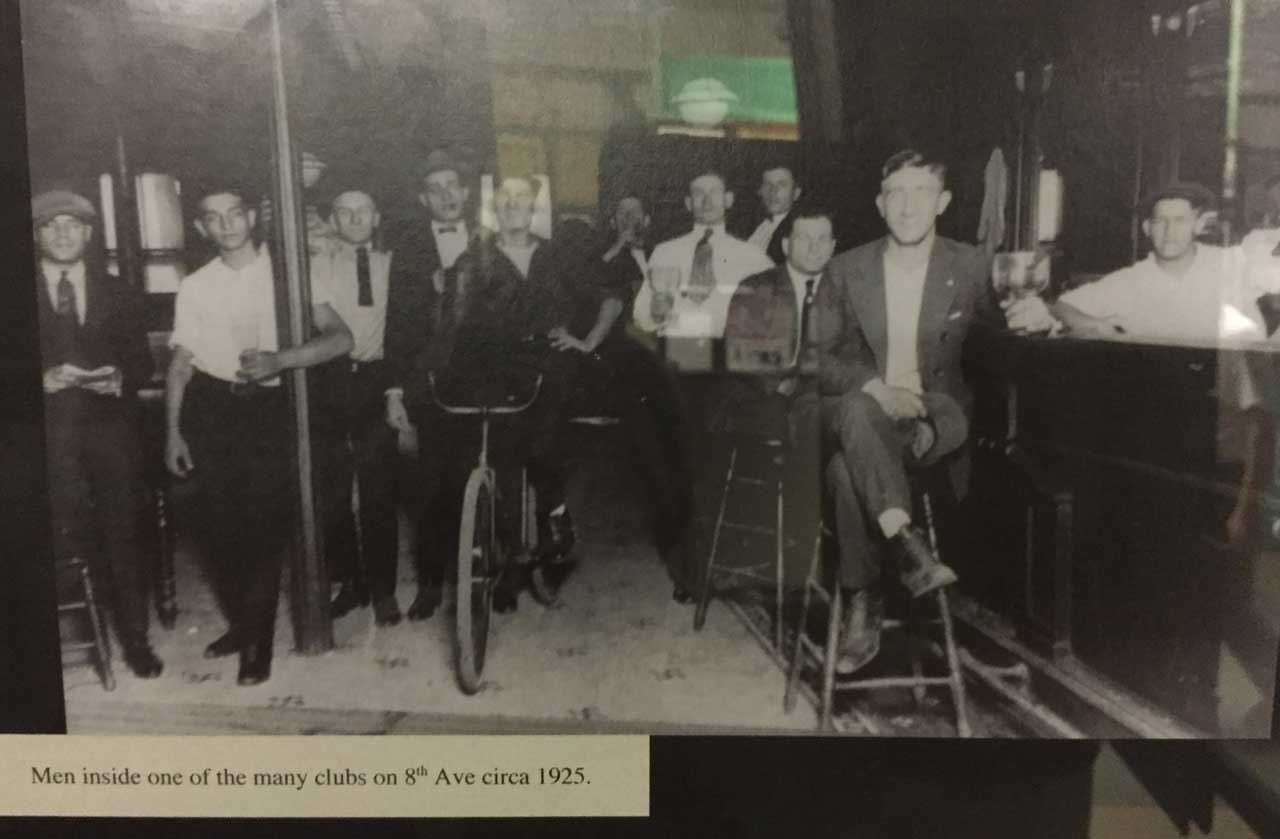

The second generation began to gain a foothold in the city, becoming the largest ethnic group in the 1940s. The city elected its first Italian mayor at the start of that same decade (note: more than two decades before its first black mayor).

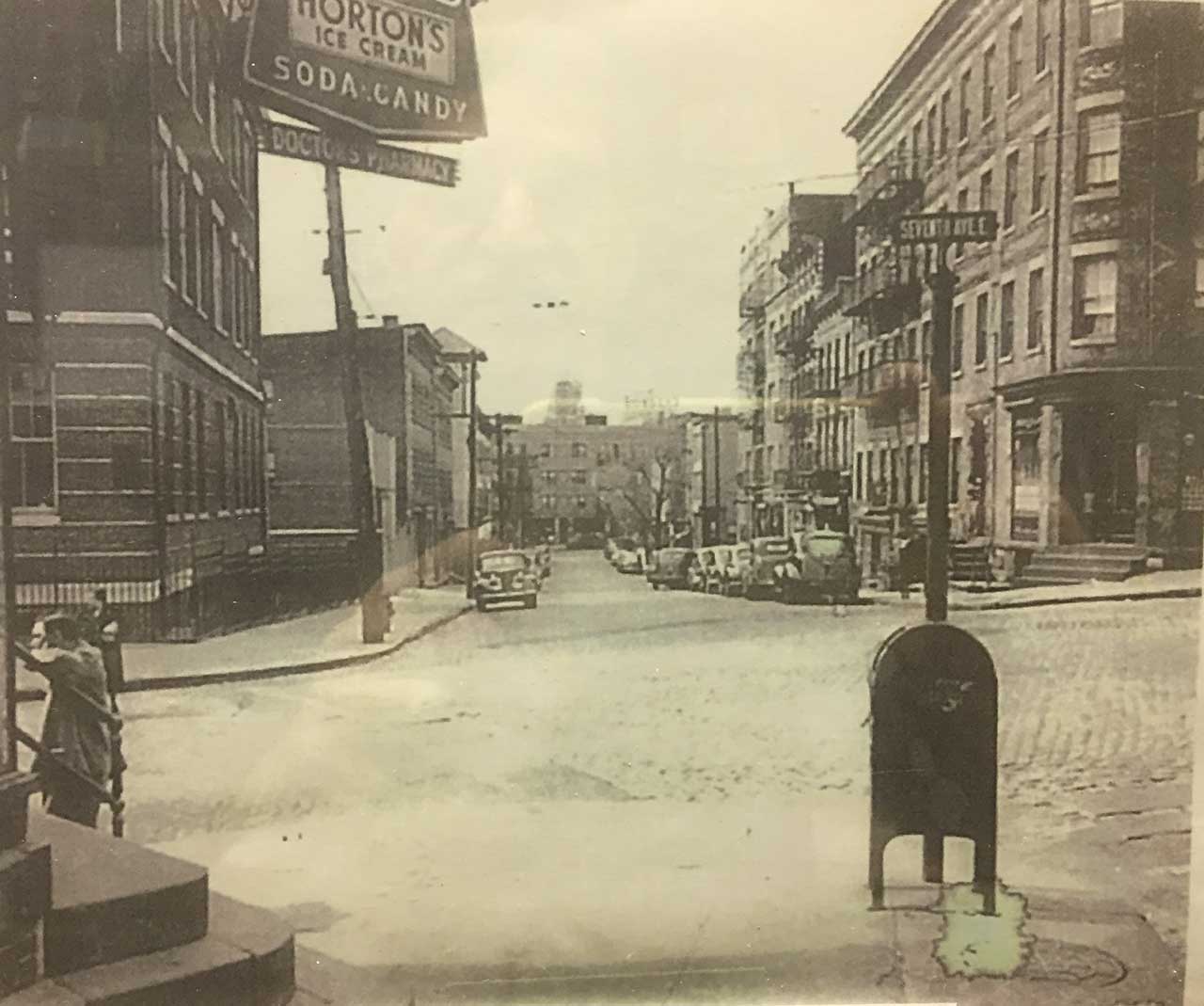

But just as things were looking up, came a dirty trick that forever changed the cityscape. Selling a snake-oil deal to First Ward residents — that urban renewal would improve their quality of life — the city in 1953 bulldozed the heart and soul of what was called the “nicest quarter in the city.” Cascella, who grew up on Mt. Prospect Avenue, said that when former Congressman Peter Rodino was trying to convince officials that the ward needed to be razed, he gave them a tour of a slum-ridden alley.

For the sake of a monstrous public housing project called the Columbus Homes, Eighth Avenue and all its charming side streets — with pushcarts, cafés, and legendary restaurants where Billie Holiday and Joe DiMaggio once dined — were leveled.

Italians generally support the fight for social justice: how could they not after what they experienced? But the way anti-racism is sometimes discussed — whether at protests or in history classrooms — makes the older generation feel their heritage is being denigrated.

Last week, in a panel, a Rutgers doctoral student admitted that students in her Marxism class refuse to cite “old white men,” including Marx. Days later, activist Shaun King tweeted that we should “tear down” statues of Jesus that depicted him as a white European. Then, at a Black Lives Matter rally a few weeks ago in Verona, Stephen Iannucci, a retired secret-service agent who was born on Summer Avenue, listened to a high school student of Italian descent tell a newfangled version of his history: “Racism does not end,” the student said, “until our country no longer stands on the racist history that our ancestors created.”

“Don’t call us racist — that’s not why our ancestors put those statues there,” Iannucci said. “These statues were a gift to the cities where our families settled — that’s why this is an insult to Italians. This should be a dialogue, not a lecture.”

It doesn’t require a degree in the African diaspora to understand why some Italian-Americans are so stubborn about Columbus. Most people, even Mother Cabrini, are bound to get upset when a gift is returned, more so when it is stomped on the ground, beheaded, or chucked into a dirty river.

But if we want to live in a more inclusive society, revisions to history are necessary, warns Mary Rizzo, a professor at Rutgers-Newark. “History is a process,” Rizzo said last year at a panel in Military Park hosted by Monument Lab. “Certain people decided that certain stories were going to be put forward, and that creates a process of power.“

Doesn’t removing a monument that commemorates an ethnic group — a group that literally helped build the city with its bare hands — at least warrant a public forum? The statue in Washington Park was removed in total secrecy. Contractors attempted to remove the North Ward statue as well, but community members were tipped off by a city councilman in time for them to surround the monument.

Instead, protesters — as well as local governments — are bypassing the usual democratic channels, claiming they lead nowhere. Mike Forcia, who infamously stood on the neck of a toppled Columbus statue in Minnesota, complained that he had been protesting that monument for two decades.

Perhaps a better conversation to have with the Italian-American community is, what enabled First Warders to beat the odds? In the 19th century, immigrants overcame many of the same hardships we see today, including discrimination, economic recession, and pandemic, according to Newark’s Little Italy.

Neighborhoods prevailed by banding together: bartering, offering store credit, stocking food pantries, helping friends with bills. And war veterans bought homes and attended college with assistance from the federal government (a program, mind you, that discriminated against African-Americans). All of this underscores the importance of not only supporting communities of color, but also acknowledging that institutions like the government must play a role in leveling the playing field. Especially when injustices are happening at a scale much larger than a neighborhood.

Times change. But a bronze cast changes little over centuries. Maybe that’s the problem with statues.

Indigenous people feel that removing the Newark statue is a step in “healing a wound,” according to Layqa Nuna Yawar, an Ecuadorian-born artist. “If public space doesn’t make space for your experience, and if it narrates only one version of history, then the public space is upholding established power,” said Yawar, known for his large-scale murals of people of color like Magnitude and Bond in downtown Newark.

And that’s only the beginning. “There is power and beauty in such an act,” Yawar said. “But it will not mean anything if we don’t question and abolish the underlying structures that kept those statues up.”