The Erie Railroad’s inaugural line in 1841 stretched more than 400 miles from Jersey City to Lake Erie and briefly laid claim to the longest track in the world. The golden age of trains, however, ended in the 20th century leaving behind a mess of abandoned tracks crisscrossing New Jersey.

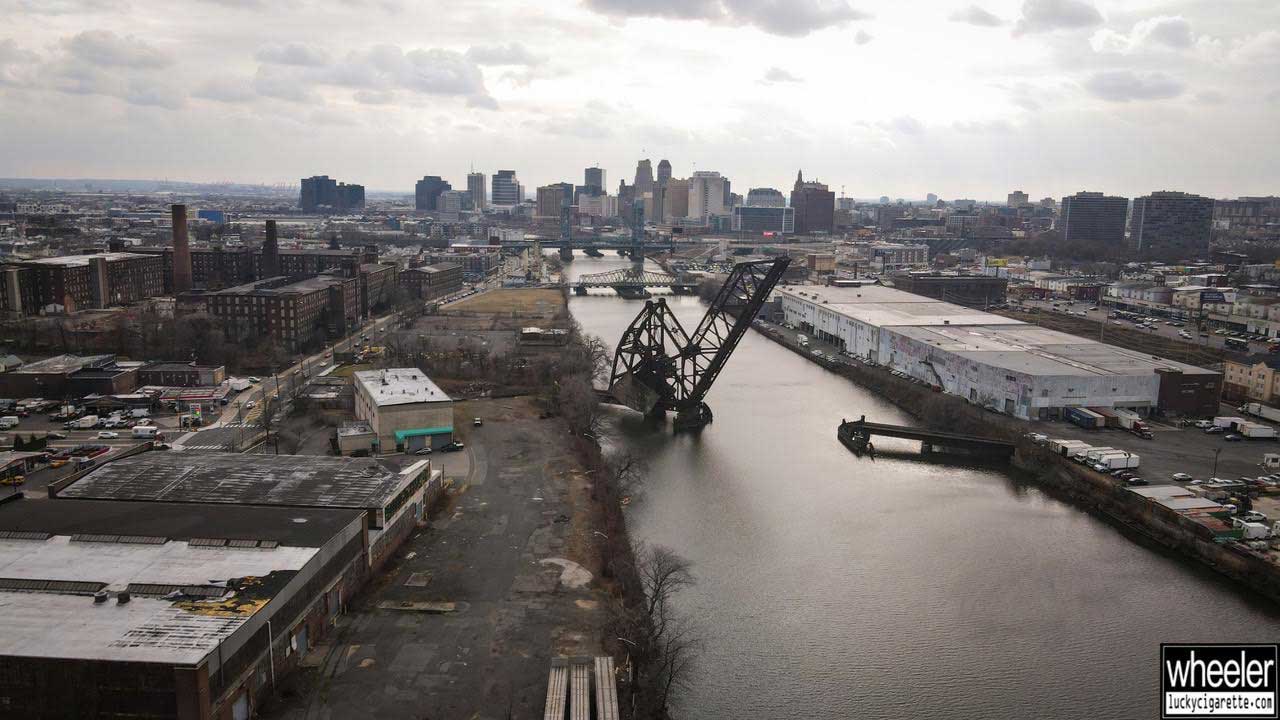

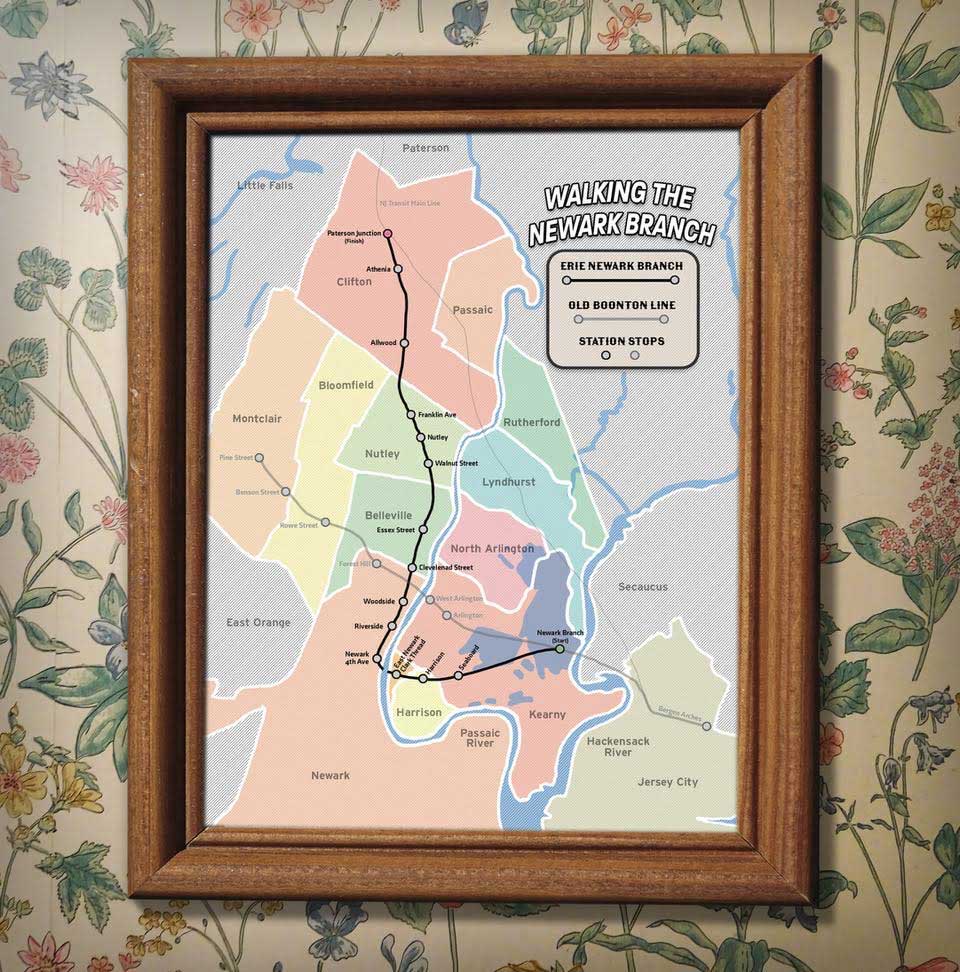

One of those forgotten tracks is the Newark Branch of the Erie Railroad, whose last train left the station four years ago. The route from Jersey City to Paterson, more than 10 miles long, now cuts through a no man’s land of marshes and industrial slums. This crime-ridden trail has become the bane of community leaders, but a muse for urban explorers. Last year, during the pandemic, Montclair-based author Wheeler Antabanez walked the entire course. His one-man journey is now the focus of this sixth book, “Walking the Newark Branch,” which recently debuted alongside a documentary.

“I’ve been doing this before they called it urban exploration,” said Wheeler, whose interest in off-the-grid places in his home state began as a kid growing up near the abandoned Overbrook Hospital. “Every time you think that you know all there is to know about North Jersey, a new frontier opens up.”

Part of the lure of Wheeler’s work, which has appeared in “Weird New Jersey” and has been featured by a number of news networks, is that he takes his audience to places outside of the margins. He first heard about the Newark Branch from a friend, the late WFMU radio host X. Ray Burns. The impetus to walk the trail came last year after the death of his parents, who died within two weeks of each other.

“I just needed to go for a long walk,” Wheeler said. “And the train tracks were there for me.”

Watching a preview of the film, I quickly fell under the spell of Wheeler’s narration. His standout vignettes include a story about the night watchmen at the Clark Thread Factory in East Newark and a lost memorial to a 19th-century engineer. The cadence of his reflections on these beautiful and bleak places has a lulling effect.

Much of the seediness Wheeler witnesses during his trek — rusting barrels leaching out noxious chemicals, rundown warehouses, shooting galleries, and prostitution strolls — have been decried by local leaders, who are leading a push to convert two abandoned railway lines that pass through Newark — the Newark Branch and the old Boonton Line, both owned by freight company Norfolk Southern.

“Norfolk Southern has not been a good neighbor to the City of Newark, to the residents of the North Ward, since they’ve taken over this property,” said Anibal Ramos, the North Ward Councilman during a recent panel hosted by New Jersey Walk & Bike Coalition (NJWBC). “Since I’ve been on the city council for the last 14 years, we’ve dealt with growing quality of life issues stemming from the inactive line, from illegal dumping to inappropriate temporary uses, like prostitution, you name it.”

Abandoned rail lines could soon be a thing of the past because they often become a sanctum for criminal activity. The NJWBC is part of a coalition of nonprofits trying to convert the old Boonton Line into a nine-mile linear park called the Essex-Hudson Greenway. The Newark Branch, meanwhile, could be converted into a light rail, connecting two of the state’s largest cities.

While communities rush to erase these places, urban explorers bemoan the loss of these secret trails that offer a unique kind of “freedom,” Antabanez said. “It’s good to get out here while it’s still here,” Antabanez said in the film. “It’s good to get out here while I’m still here.”