This is a guest post by R. Ballantine

Newark is a city of contradictions, both blessed and cursed by its history and most obviously its location. Its relationship to our pompous neighbor across the Hudson was always one where if we could ascend above their shadow, we would emerge triumphant in the eyes of both Garden State residents and our own downtrodden post-industrial contemporaries. We are always David trying to defeat Goliath, planning, dreaming, continuously strategizing how we could finally best this titan at its game of economic prowess and cultural capital. All this potential, however, sits idle because of a history of self-sabotage, misguided expectations, and powers beyond our control.

That’s what I think every time I pass this infamous lot beside Broad Street Station. Once the site of the Westinghouse Factory, it has sat vacant for over 14 years without any real plan for redevelopment. Not even the owner of the site bothers to turn it into a parking lot, the most stereotypical response to wasted potential. It sits vacant, a wildflower meadow blooming every spring only for it to be gracelessly chopped down every summer. Prominently sited within a dedicated redevelopment district, here we are promised the site of a bustling transit-oriented community, and yet, 14 years have gone by with nothing to show for it.

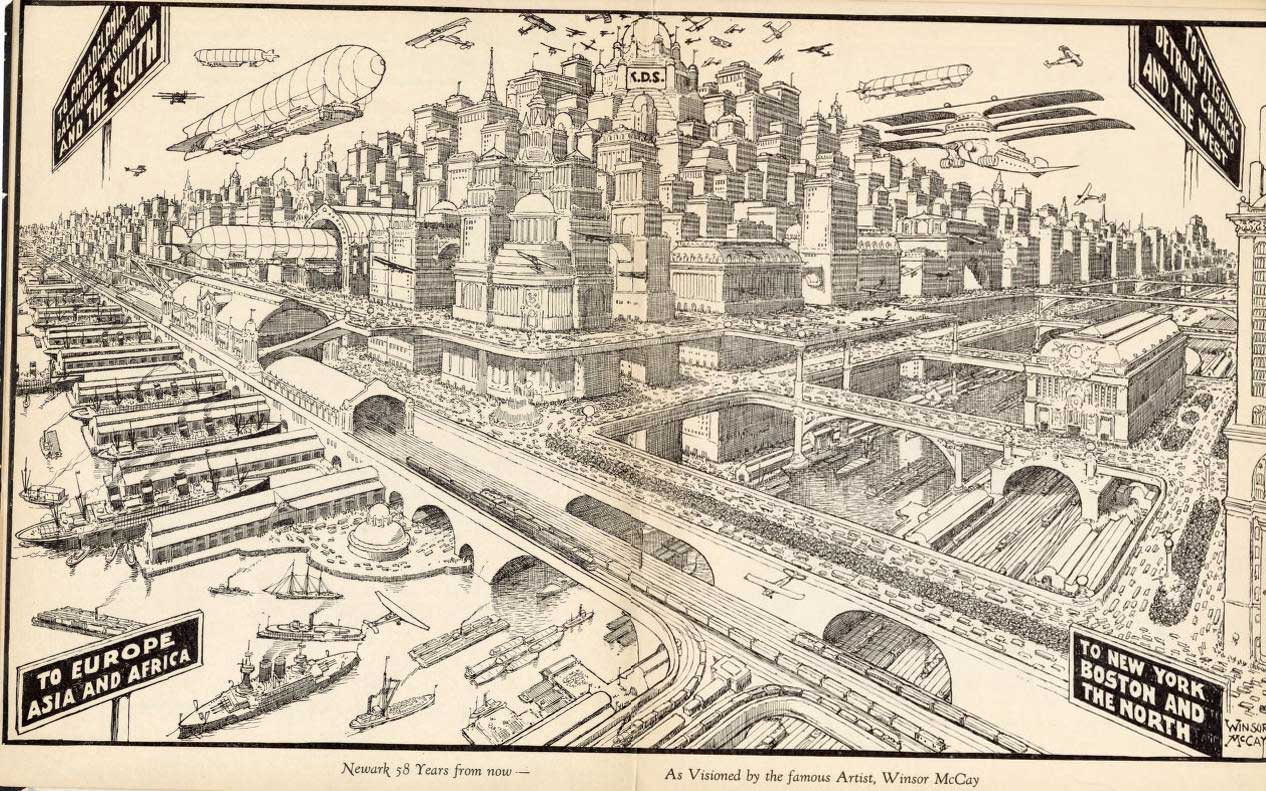

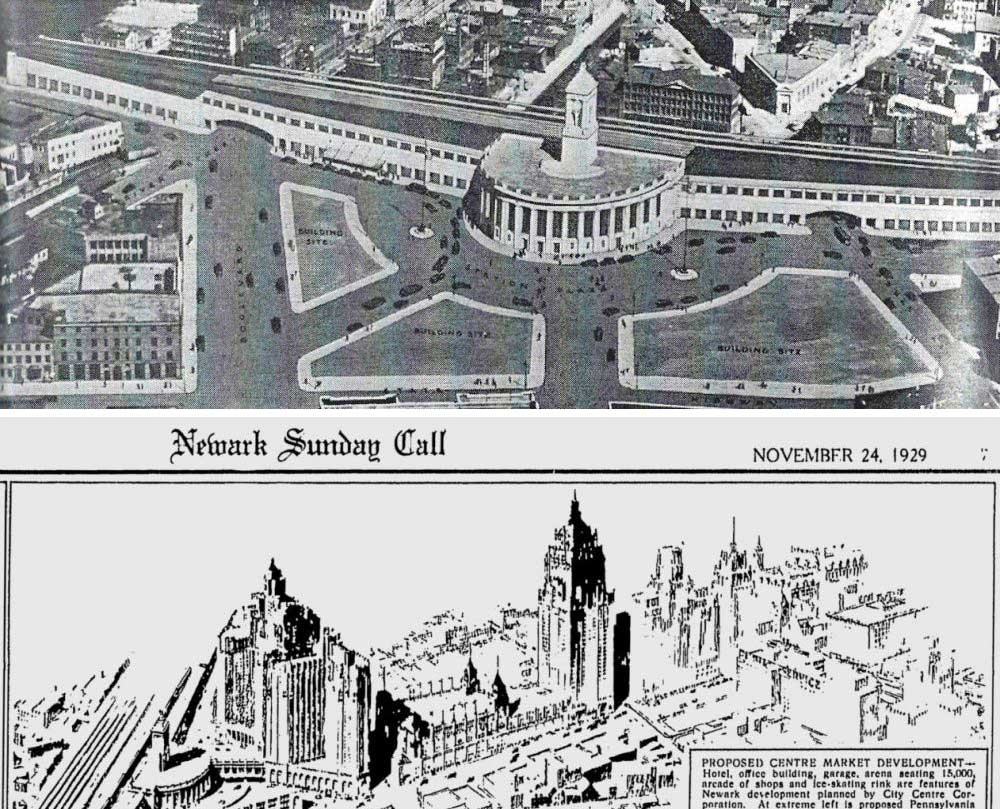

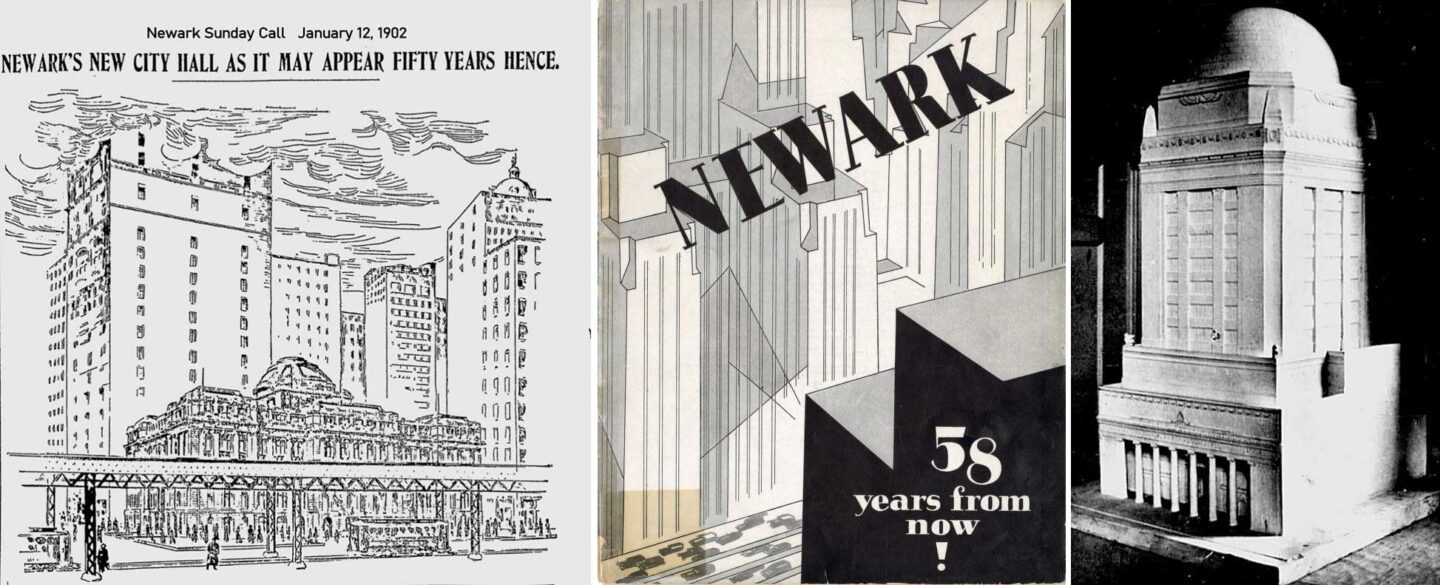

To understand why prominent sites like this one are allowed to sit vacant and undercut our city’s future, we must go back into the annals of Newark’s past. We must examine how planners, architects and leaders envisioned the path forward to Brick City’s prosperity, through projects and buildings dreamed up to beautify, renew, and transform a city always at the cusp of greatness. Few of them managed to leave the drafting table, many were all but fanciful follies.

The late 19th Century was the beginning of a brave new world for the development of American architecture and urban design. America was experiencing several decades of rapid industrial growth and was quickly proving itself a dominant competitor to the industrial Empires of Europe. But the United States at this point lacked an ‘Identity’ as a great power, particularly when it came to its cities and its architecture. No one could dispute the effervescence of cities like Newark, Philadelphia, and NYC, but they grew rapidly and with rare exceptions, chaotically. Disease was rampant, extreme inequality ran across society, neighborhoods caked in pollution and soot from factory chimneys, and streets choked with traffic from horse drawn carriages and their ‘leavings’. The price for becoming an industrial nation was paid with cities that were unpleasant to live in, and unattractive to look at. Politicians and business leaders across the nation wanted a way to prove to the Powers of Europe that the United States was more than just factories and farmland. And it took a world’s fair in Chicago for American cities like Newark to start proving to the world they had civic and cultural capital.

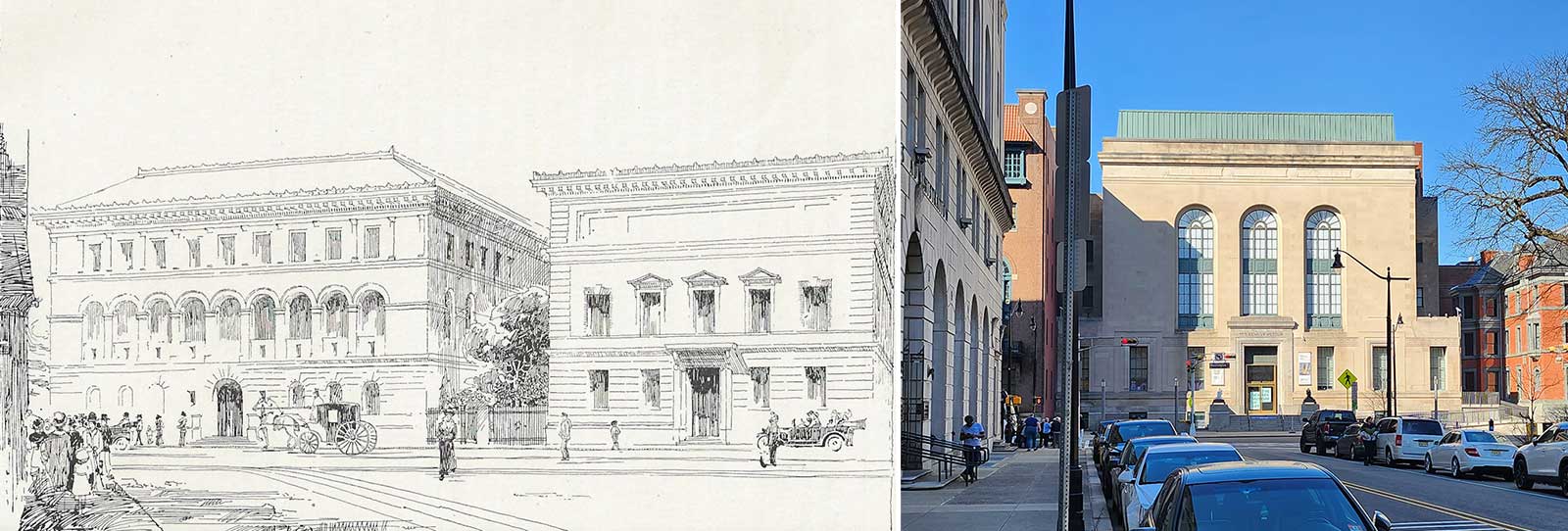

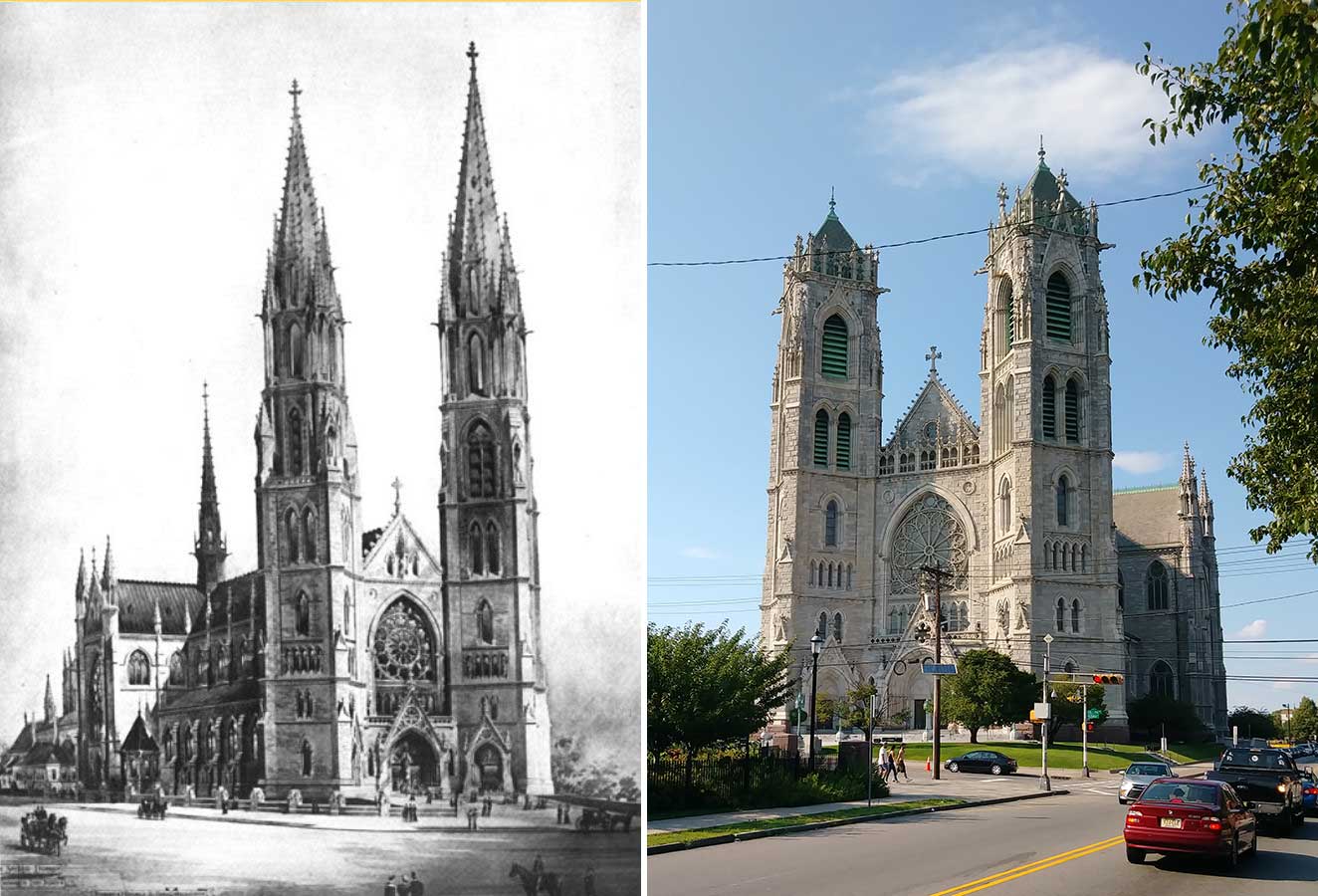

The Columbian Exhibition of 1893 proved to be the spark that would begin ‘The City Beautiful Movement’. Papier-mâché and plaster helped create a vision of an ideal city filled with great neo-classical buildings organized around grand fountains, lush gardens, and vast public spaces, all illuminated by the recent invention of electric lighting. The American public was astonished at the scale and spectacle of this exposition, and the political and philanthropic classes took notice. It became the priority of cities across the country to invest and plan great works of public and cultural infrastructure to address the urban ills of American cities, and to use beauty and nature to create civic pride and urban civility.

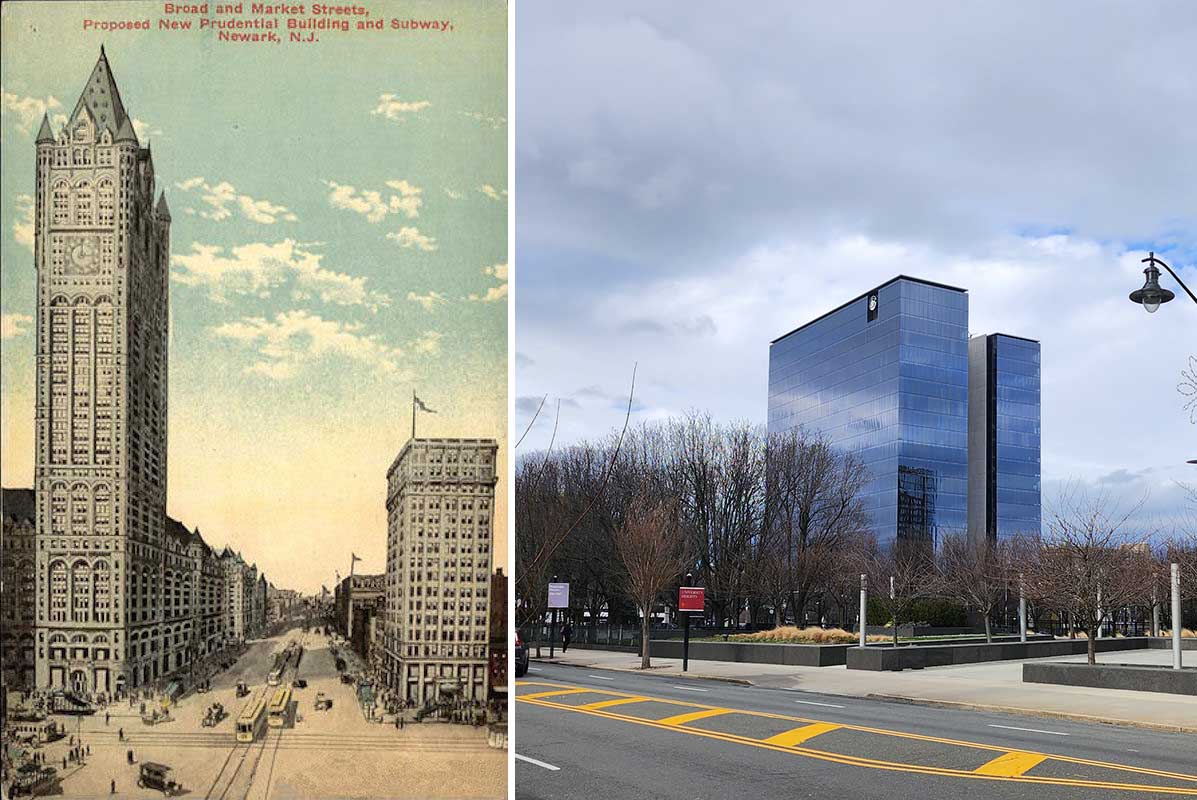

The City Beautiful Movement helped create many of the great buildings and public spaces we Newarkers now enjoy. Weequahic and Branch Brook Park, City Hall, the Central Post Office, County Courthouse, and our own public library were built in the spirit of using Noble Architecture and picturesque landscapes to not only beautify our city, but to shape the consciousness of its citizens in the attempt to mold a better society. The private sector did not want to be left out of this architectural boondoggle: banks were made to resemble Roman temples to finance, insurance companies made to look like gothic castles, and even the most utilitarian of industries were ornamented to build the reputation of being safe and prosperous enterprises. Here we start to see the dreams of what the Newark of tomorrow might have looked like, but here we also start to see that the planners and architects of the Brick City had to wait for their visions to leave their drafting tables, and in many cases, were transformed from their original visions by time and changing tastes.

The City Beautiful Movement had its limitations. Newark might have aspired to look as beautiful as the great cities of Europe, but Newark planners did not have the autocratic rule of kings and emperors who could command a tree lined boulevard be built straight through a neighborhood without objections to connect City Hall to the Opera House. Some of Newark’s greater ambitions had stalled either from lack of funds or lack of political will from a city government that was growing more unscrupulous with each new administration. Plans to build new roads through dense urban grids to ease congestion faced opposition from property owners, construction of more green spaces to combat pollution faced similar hurdles. The goal to create subway lines for Newark’s ever expanding Trolley system was equally slow-moving as investment in public transit was undercut by the popularity of the car.

Fortunately so they believed, the city’s wealth and population had been growing continuously for nearly half a century, and on the surface it looked like this trend would continue. So the hope was that eventually these key projects would be completed in one format or another… then came the Crash of 1929.

What could be completed was done so, but the ambitious projects of years, sometimes decades earlier, were scaled back. The goal was no longer to celebrate a city’s greatness through architecture and urban design, the goal became providing jobs to keep what little prosperity remained, with the help of the federal government funding these projects during the Works Progress Administration. The fantasies created by the private sector however, blew away with the wind, lost with profits and fortunes that had now turned to dust.

The Depression and the Second World War helped hide a trend that city planners ignored, and business leaders denied, Newarkers had begun leaving the city for the suburbs during the 1910’s and into the 1920’s. The investments in grand civic and cultural institutions were not enough to overcome the fact that Newark was still a polluted, traffic choked city. There were still not enough green spaces, and that mismanagement of city funds resulted in wasted opportunities for urban improvement. Economic downturn and war just suppressed a trend that had already begun during Newark’s boom years.

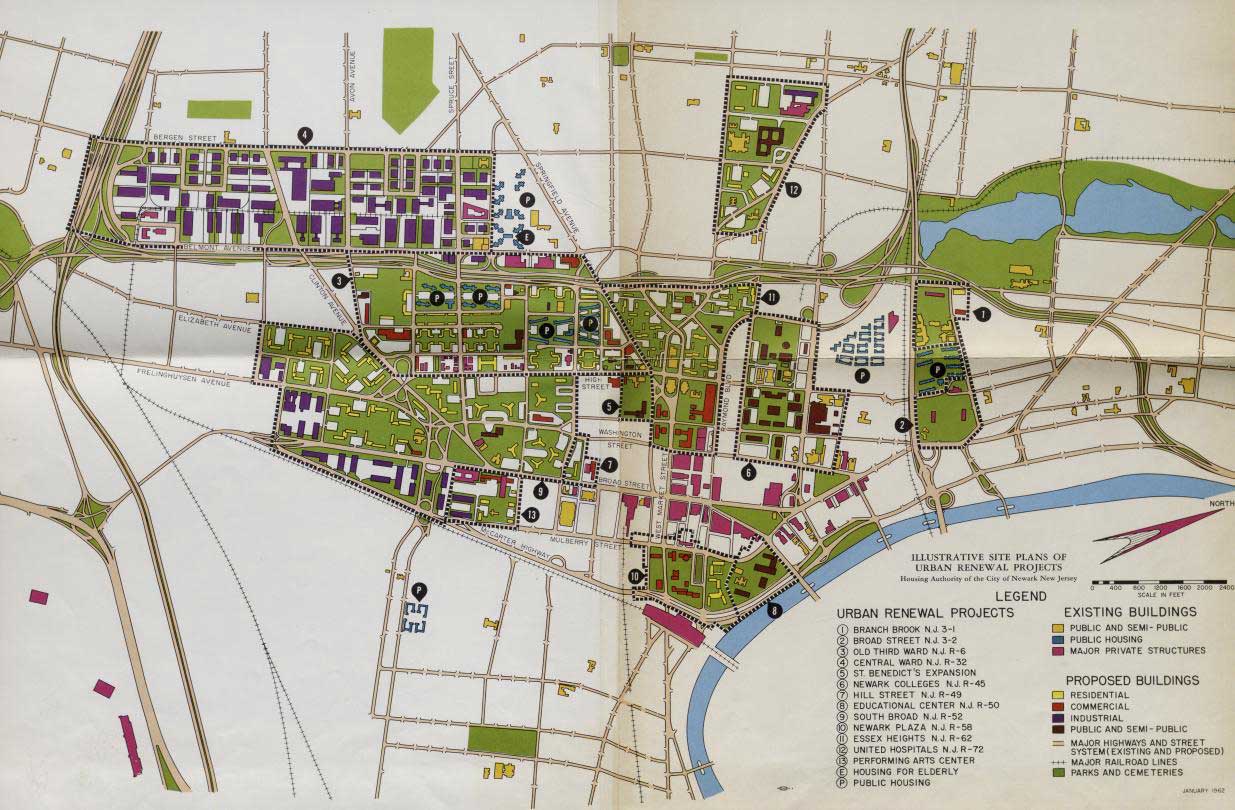

With the end of the war and the Mid-Century rapidly approaching them, city leaders were caught off-guard and they decided to throw every rule about city planning they had out the window. They needed to rethink the entire way people thought of living in an urban center to save the Brick City from further economic ruin. And in doing so, they not only created the downfall they feared, but they also almost erased the city of Newark out of existence.

Join me for Part II of this tale of the Brick City that could have been… the missteps and flawed dreams of a Motorama future, of Neo-Liberal malpractice, and the compounding crises that are shaping Newark’s future today.