This is a guest post by R. Ballantine.

Part 1 is here. Part 2 is here.

Welcome to Newark, the Renaissance City! At least that was the tagline that municipal and business leaders were going for during the 1980s. The tagline was used to push hard that Newark had finally leveled off from the precipitous decline that consumed the city for the last 20 years. That was as much a lie they told themselves as the truth that was self-evident as you walked through the street of a Brick City in shambles.

Businessmen upsold on the completion of the second and third stages of Gateway Center, yet the Lefcourt Building (1180 Raymond), then the second tallest building in the state, had been left abandoned. 80 Park Plaza (PSE&G Headquarters) was celebrated, at the cost of demolishing the Public Service Terminal, and replacing it with a large albeit vapid plaza.

No one dared walk through downtown Newark after dark. Bamberger’s gasped its last breaths as the last surviving department store in the city, and the great movie theaters were shuttering one by one. City leadership kept playing cheerleader to attract people to come, while resorting to beggary for existing residents to stay… their pleas were too little too late, the only residents that stayed where the ones who had absolutely no means to leave.

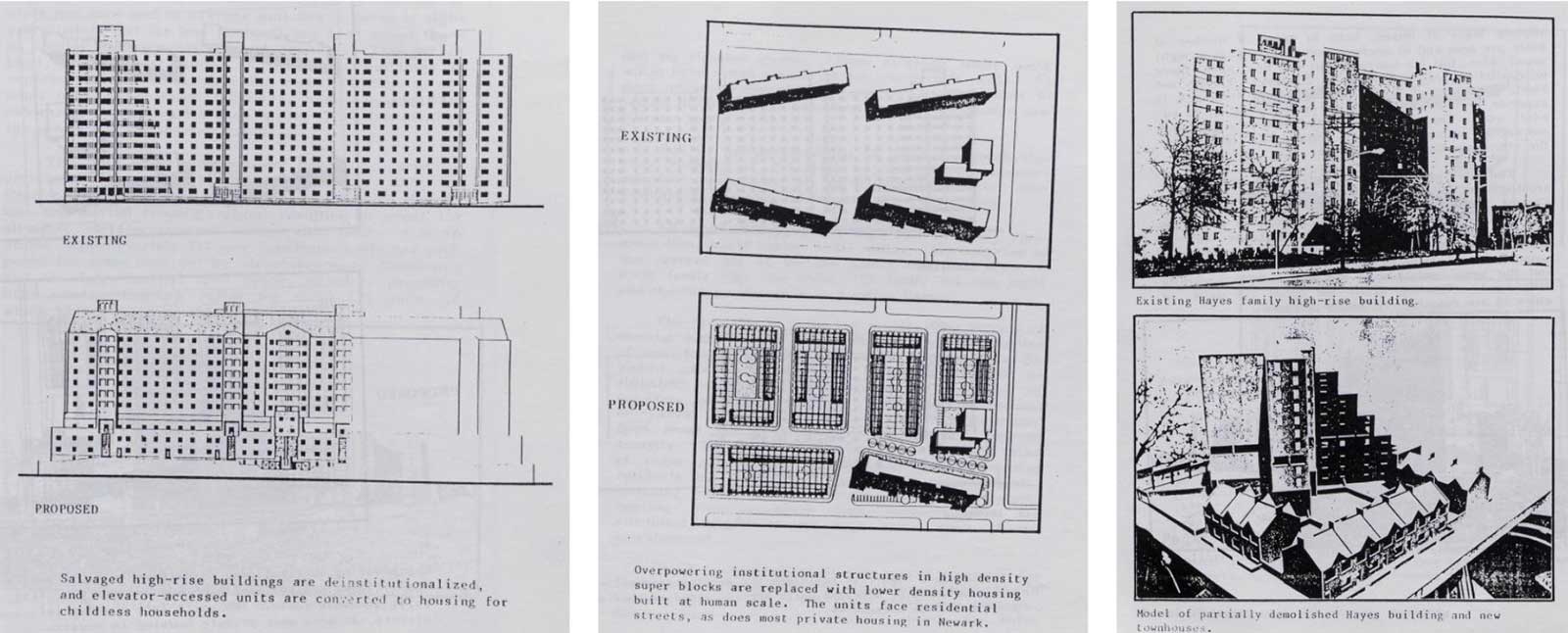

Newark planners did not know where to go from this point forward. The city was being drained of the political or economic power to affect any meaningful change, they were too slow to act in the pre-war era, and the sweeping changes that were made for urban renewal had come back to slap them across their faces. What they could plan for was not a bold vision of how to bring people back, but to clean up the mess that came from flying too close to the sun.

The business community was no longer convinced of the opinions of city planners. They had bought into the promises made during the 1950s and 60s, and it all proved disastrous for their bottom line. These businessmen, with shareholders and investors to answer for, viewed these urban intellectuals as oblivious to the needs of market demand for real-estate and middle-class consumer tastes.

There were also persons holding positions of power in City Hall who had suffered directly from the heavy hand of urban renewal’s top-down planning, they were elected to dismantle the institutions that destroyed their respective communities. When they took power, these politicians spoke gallantly for ending these injustices… but behind closed doors shared the same distaste of (perceived) out-of-touch academics.

What began to form was a rift between the city planning agencies, and the desires of the economic leadership that still clung to power, who were making themselves privy to decisions made at the highest levels of municipal governance. But it was all a moot point, they did not have a clue on how to affect market-based solutions that would help the city get out of its death spiral, that was until Harry Grant showed up at the doors of the Brick City.

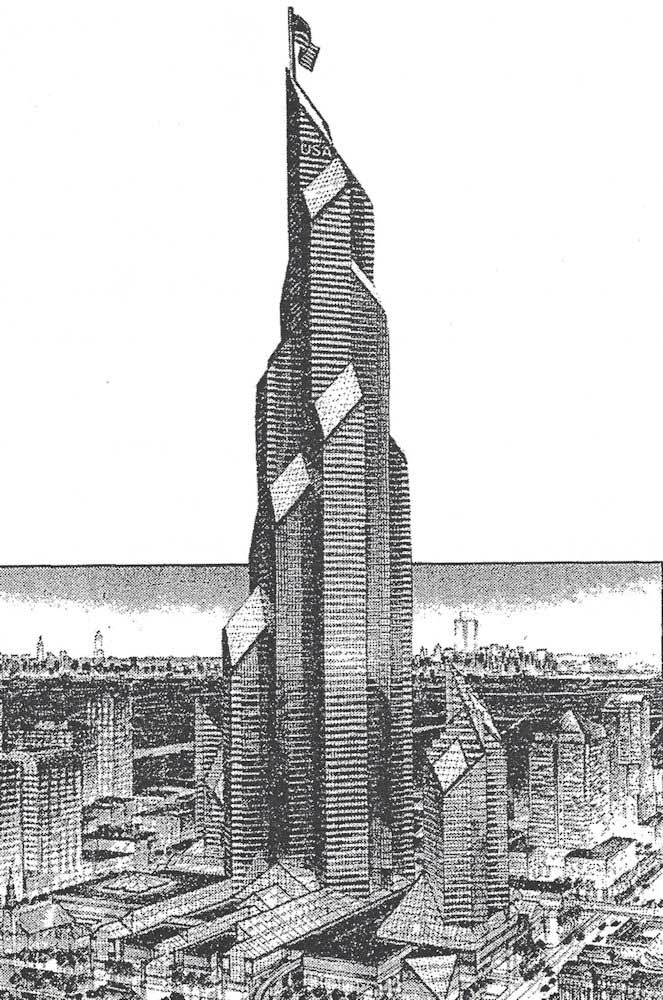

He had appeared as if out of thin air. This Iraqi born immigrant, with an Americanized name, created a vast real-estate empire worth over a billion dollars and became owner of NYC Bus Tours. Mr. Grant summoned the Mayor and City Council to an impromptu press conference in 1986, and in front of the entire world announced his plan to revive Newark with a project that was unbelievable in every conception.

He proposed a vast neighborhood-size complex with a convention center, a 200,000-square-foot shopping center, a 5,000-car parking complex, renovation of the abandoned New Jersey Central Railroad Terminal, a free monorail connecting Newark Penn Station to Newark Airport, and crowning this sprawling endeavor was a 1,750-foot tower comprising 3,000,000-square-feet of commercial space. Clad in dollar-green glass and gold trim, enormous golden letters would spell out USA at its crown, finishing off with a star spangle banner fluttering in the breeze at its zenith.

City Hall was gob smacked, and our pompous cross-Hudson neighbor looked on with bizarre wonderment at how their fallen neighbor could attract such attention. The first phase of his plan would begin with the construction of the marble-clad shopping center to be known as Renaissance Mall, the opening scheduled for 1990.

The mayor thought this project was a miracle sent from above, and he was further persuaded when Mr. Grant gifted City Hall with its gilded gold dome. The city green lit the further demolition of downtown to allow room for this mega-project. But soon enough Mr. Grant’s generosity began to sour with the mayor. Work crews were replacing sidewalks with imported pavers around Mr. Grant’s project, but they kept working all the way up to the steps of City Hall without municipal approval. The mayor filed trespassing charges for such brazen disregard for public property.

Alas, this trickle-down excess would come to naught as a recession in commercial real-estate took hold in the late 1980’s. Harry Grant’s creditors came knocking, and his business empire would soon become insolvent. Mr. Grant’s 1,750-foot tower turned into another parking lot in an ever-growing urban wasteland.

This humiliating folly, however, gave the business community an idea, what if you could create a major symbolic work of public or private merit, and then create a whole district dedicated to re-invigorating the neighborhood around said project? What the Grant proposal showed was that market response was more interested in the indirect impact of this now defunct skyscraper than the skyscraper itself. And through pure serendipity, the governor of New Jersey was looking to invest in large works of cultural infrastructure to help regenerate various underserved cities in the state. In 1988, this resulted in the creation of the New Jersey Performing Art Center, and a special redevelopment zone encompassing the immediate lots beside this future cultural mecca.

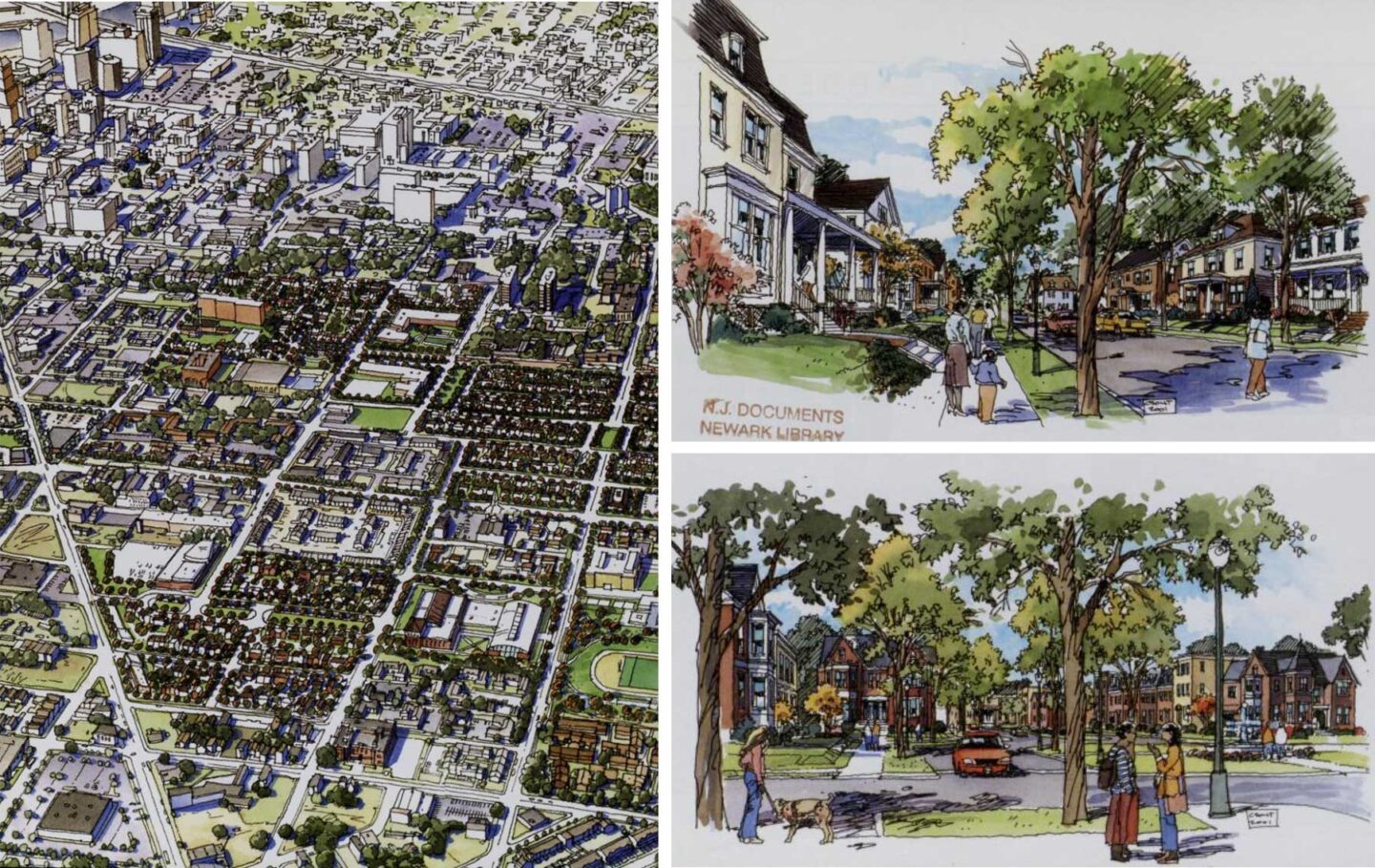

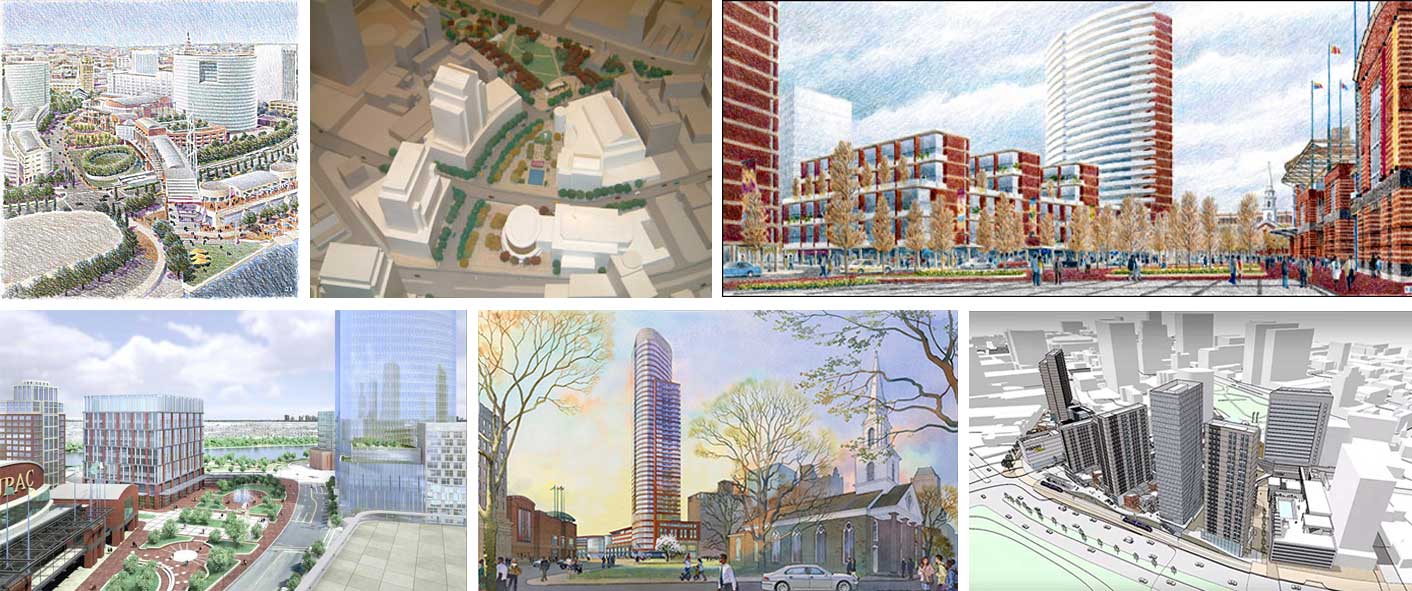

The solution as it appeared was the development of partnerships between public and private agencies. Government entities would provide the upfront cost and investment in the form of major public works, and in return the private sector would be afforded concessions in the form of greater zoning allowances and tax benefits to promote development around these mega projects. It was neo-liberalism’s answer to the grand scale projects of the City Beautiful Movement without the governmental overreach and stigma of Urban Renewal.

From this era, we saw the creation of the Penn/Broad Street Station Light Rail Loop, the building of the (now demolished) Newark Bears Baseball Stadium, and in the early 2000’s the construction of Prudential Center Arena with its own special redevelopment district. On paper it looked like the perfect union between two irreconcilable foes in the battle to regenerate a crestfallen Newark.

This was all but pretense; the public sector’s goal is to invest in the long-term health of communities and their continued growth for the benefit of taxation. The private sector’s goal is to make money and provide profits to its shareholders through short-term plans and tax avoiding strategies whenever possible. Landowners and speculators knew that by buying into these special districts, they would benefit from an increase in property values, and so long as they did the bare minimum in physical investment, they could derive the profits they desired at minimal cost. It was cheaper and more effective to create parking lots to service car-dependent traffic than risk the expense of building high density housing and mixed-use communities… hence the empty Westinghouse Factory lot from Part I.

As the growth of the 1990s evolved into the housing bubble of the 2000s, special development districts were created by the private sector exclusively. Speculators found a friendly ear with City Hall, who could promote sweeping new developments to their constituents to show Newark was finally re-emerging as a great urban center, boosting re-election prospects, and securing political contributions (legal or otherwise) to remain in power. Downtown’s valuable land was auctioned off to the highest bidder, and high net worth speculators with their high-priced cross-Hudson architects and Bergen County law firms created self-serving masterplans to feed their ballooning egos and their investors’ mania.

And if any significant historic buildings found themselves in the way? Well, if the mayor says it’s okay… bring on the bulldozers. Newark Landmarks could do nothing but watch this city’s legacy be turned to rubble because City Hall favored the speculator’s gold over Newark’s urban memory. When the housing bubble burst in 2007, Newark was once again stuck in a compromised position, downtown development returned to sputter with sporadic projects, but now the Central Ward was chained by bureaucracy that limited the powers of city planners to correct Newark’s urban dysfunction. Downtown was surrendered to developers and corporations whose only goal was to turn Newark into a second rate version of Long Island City.

And so where does that leave us now? Newark has, in one way or another, gone through the urban equivalent of the five stages of grief in its response to losing its chance to stand shoulder-to-shoulder with its cross-Hudson rival. The denial of the 50s and 60s, the anger of the 70s and 80s, the bargaining of the 90s and 2000s. And now in 2024, we seem to have finally crawled out of our long depression, as construction cranes rise with new investments in high density housing, and the slow but sure return of retail and dining in our urban core.

Perhaps now we have come to terms and accepted that we had all the makings of becoming “The Metropolis of Tomorrow”, but the twists of fate never allowed the right people, the right timing, and the right conditions to align themselves so that our great city would finally reach for the stars and ascend to the pantheon of greatness.

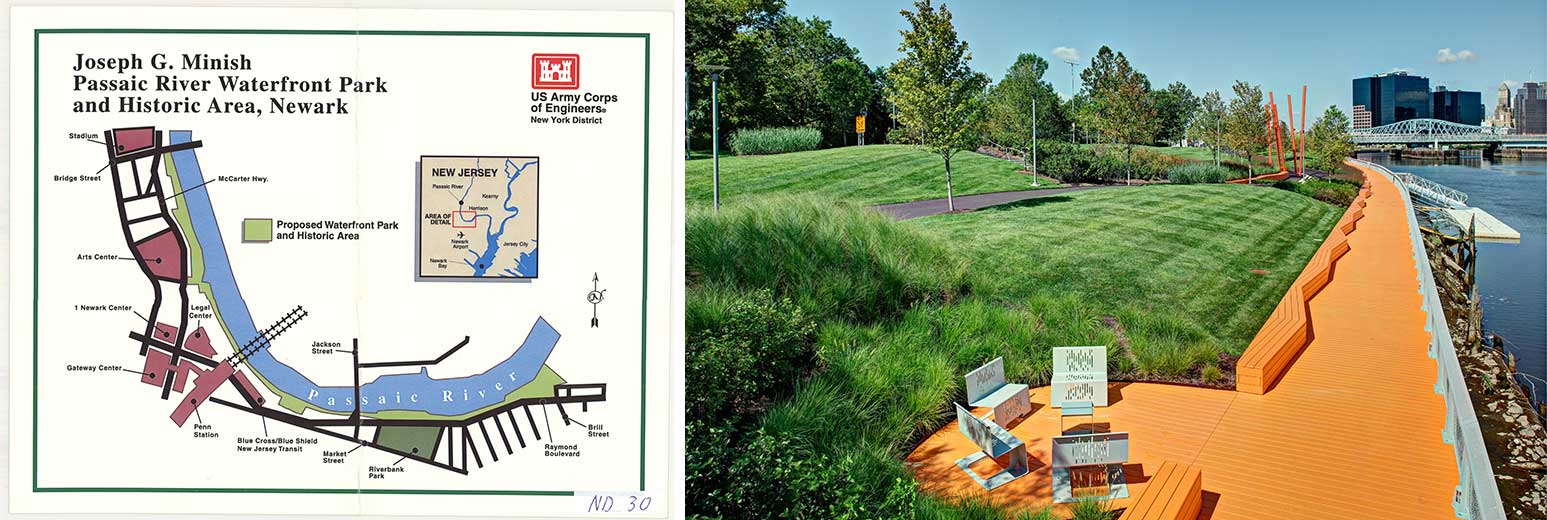

The only thing we should never accept is the status quo, however… Newark, after all these decades of promising a greener, friendlier, and more equitable city, still has not built any green public spaces in areas of the city that most need them. We still suffer from the highest rates of asthma and pollution related illnesses in the country. Our public transit system is chronically insufficient to meet the demands of serving disadvantaged communities, while pedestrian friendly neighborhoods are becoming the redoubt of affluent newcomers that still prefer the luxury of owning a car. And an opaqueness still exists between Newarkers and City Hall, where well-meaning planners and architects call for transparency to help Brick City residents raise their long-term quality of life, while municipal governance only preoccupies itself with its own self-serving political ambitions.

The greatness of Newark only rests with its people, the social contract between the representatives that serve us and those we appoint to power must be made accountable again. Without accountability, the battle for our city’s spirit will be lost to the indifference of Wall Street and to the regressive obloquy of the suburbs. Only then we will stop pondering about the ‘Newark we could have been’ and see the Newark that we can become.