This is a guest post by R. Ballantine

Part 1 is here.

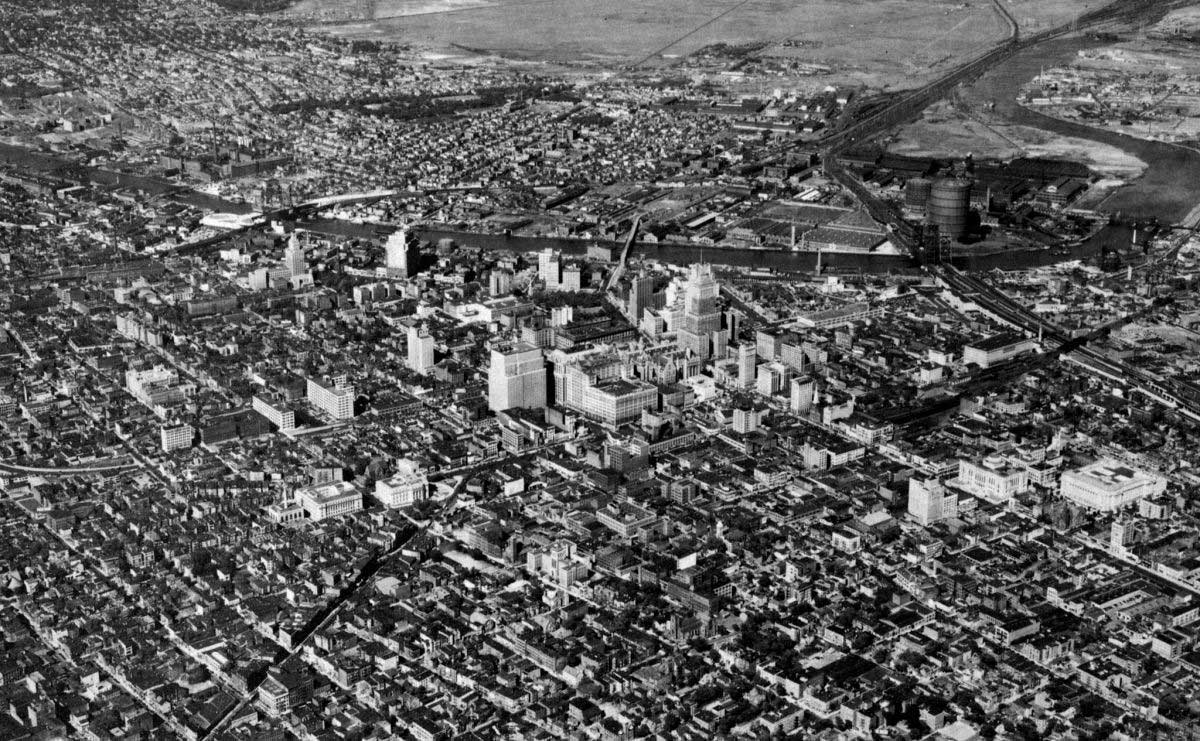

Newark after World War Two was a city exhausted by the burden of a decade-long economic slump, and the four grueling years of sacrifice that helped defeat evil forces across the globe. The image you see below is a city that grew sprawling and dense from centuries of organic, albeit chaotic growth, the burden of being the Garden State’s economic heart was taking its toll.

Ruinous tenements dotted themselves in the oldest parts of downtown and families lived in squalor. The public housing projects of the Works Project Administration were not enough as the Brick City continued to swell with migrants from the Southern United States and refugees from war-torn Europe. Newark continued to lack public green spaces, with existing ones only serving the city’s more affluent residents. The influence of the car stalled during wartime, but sooner or later it would return, and traffic and pollution would once again consume the city streets.

Now the war was over, our enemies were defeated (until the Cold War kicked in that is) and Newark needed to reset itself in this era of peacetime and prosperity for a brighter tomorrow yet to come. City leaders and planners re-evaluated the ambitions of the Pre-War Era and realized that those earlier projects and plans were not enough to affect the real changes needed for Newark to remain competitive with NYC. They needed to be bolder in the way the city would develop for the next 20-30 years. They needed to radically alter the way things were done, and during the mid-century, they took a gamble on what was to be the city of the future.

By the 1950 Census, Newark’s population had bounced back from a 1940 dip to 438,000 inhabitants. This population dip was misconstrued by planners and city leaders as an anomaly, and any fears that its citizenry would leave on masse for commuter villages like Montclair and the Oranges was not viewed as a serious threat…yet.

Newark’s planners were fueled by a new optimism for rekindling the hopes of transforming Brick City into the great Garden State Metropolis that its forefathers once hoped for before the war. Down with the old, in with the new, Newark would follow the lead of other American cities in a new world where America emerged as the most powerful industrialized nation on Earth.

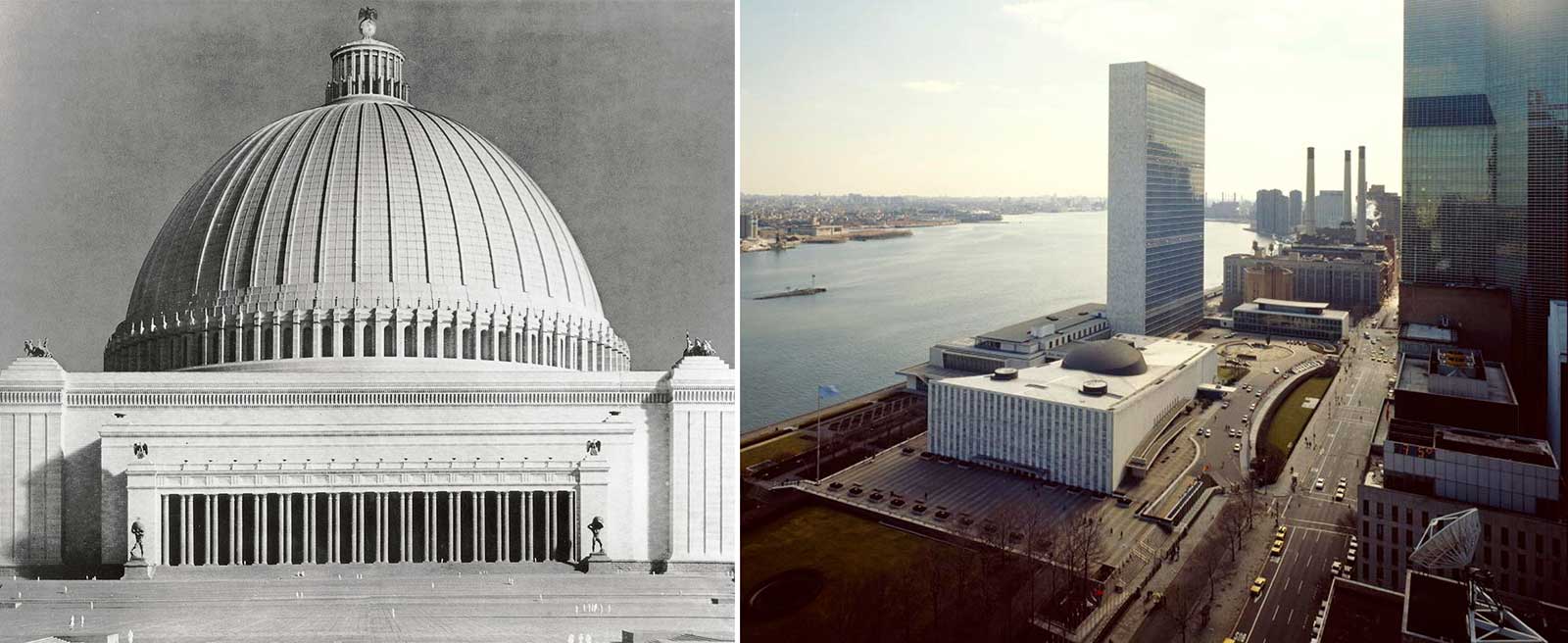

The irony was that this new vision of the new American City was not our own, but once again copied from Europe. Specifically, by European architects who viewed the ornate buildings and pompous public spaces of European cities as tainted with class inequity and social Darwinism. To them, the whole architectural regime had become a symbol of the stagnant and profligate upper classes, whose callous dominance over the populace resulted in the First World War, and with nationalist tyrants who used ornamental architecture to manipulate the masses, in their vainglorious pursuit to plunge the world into perdition. Many of these thinkers were forced to flee to the United States to escape an Old World rapidly devolving into madness.

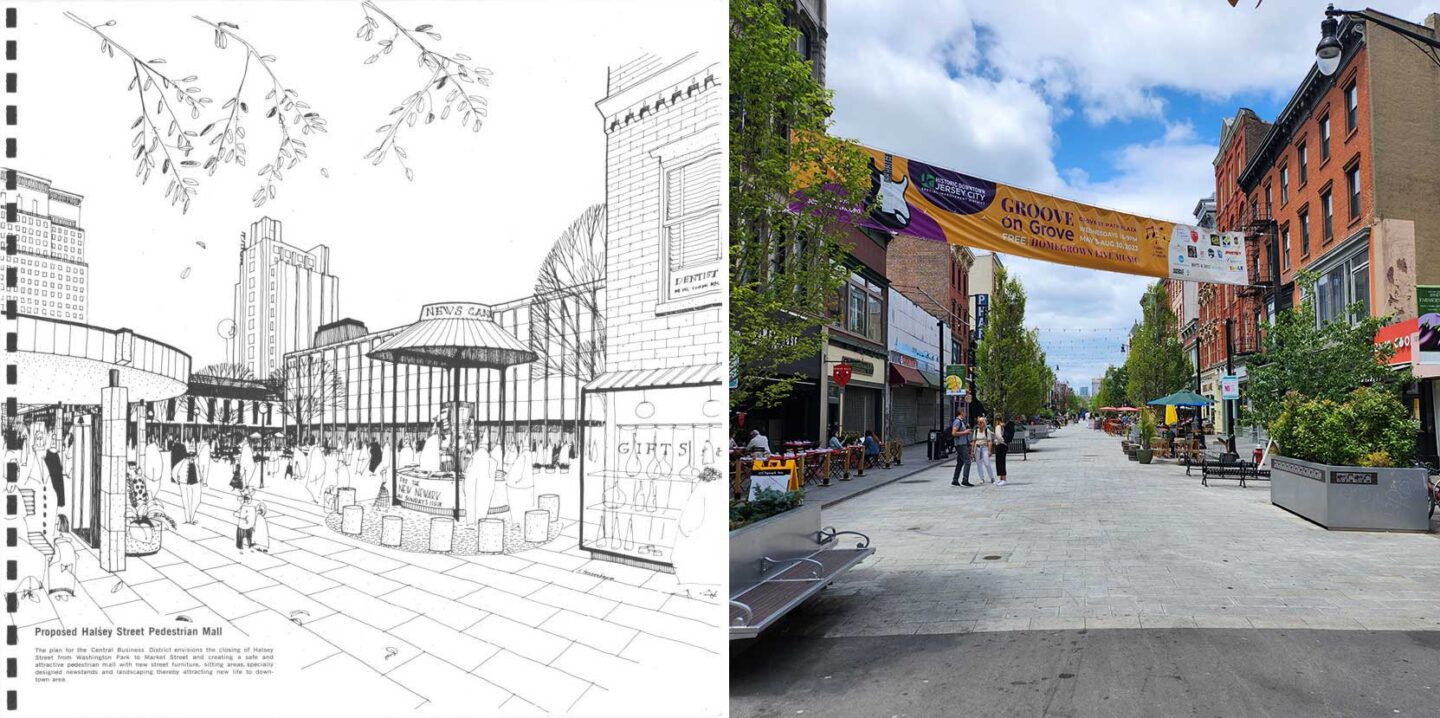

This was an unprecedented departure from the imaginings of tree-lined boulevards and classical public buildings of the ‘City Beautiful Movement’, nor were there any hints of the soaring, Art-Deco frivolity of the 1920s. The Newark that planners wished to create after World War II was to reflect the technological promise of a tomorrow yet to come. We no longer wished to copy the cities of Rome and Paris, we were now masters of our own urban reality.

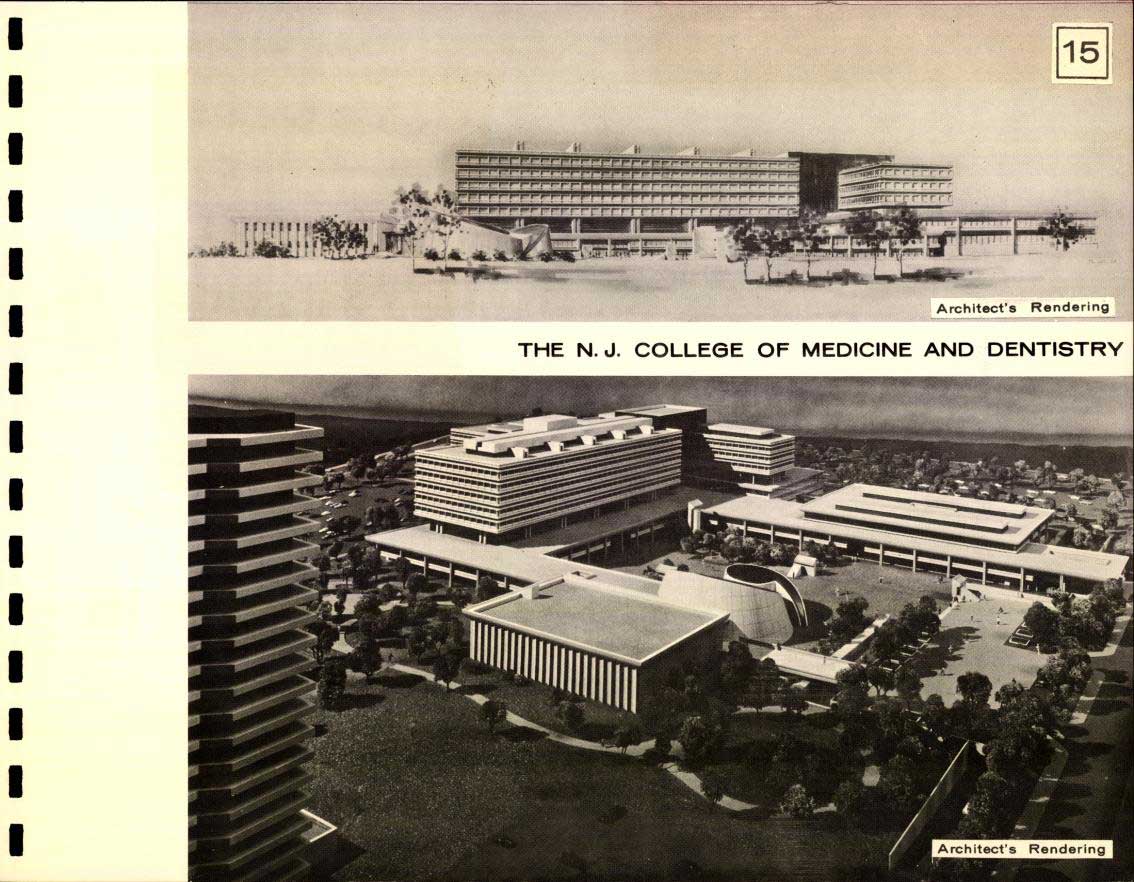

Architects called for creating buildings and cities devoid of class and nationalist distinctions. Buildings that would be functional and rationally planned, with plenty of sunlight, greenery, and fresh air. Factories, offices, and housing would be segregated into dedicated zones interconnected by transit corridors for ease of movement. The common office clerk and school janitor would be afforded the same urbane dignity of a clean and orderly city as an industrialist or judge. The promise to create a truly democratic, egalitarian, technocratic society appeared on the horizon, and with Federal backing and State authority, Newark jumped head-first into the Urban Renewal Era.

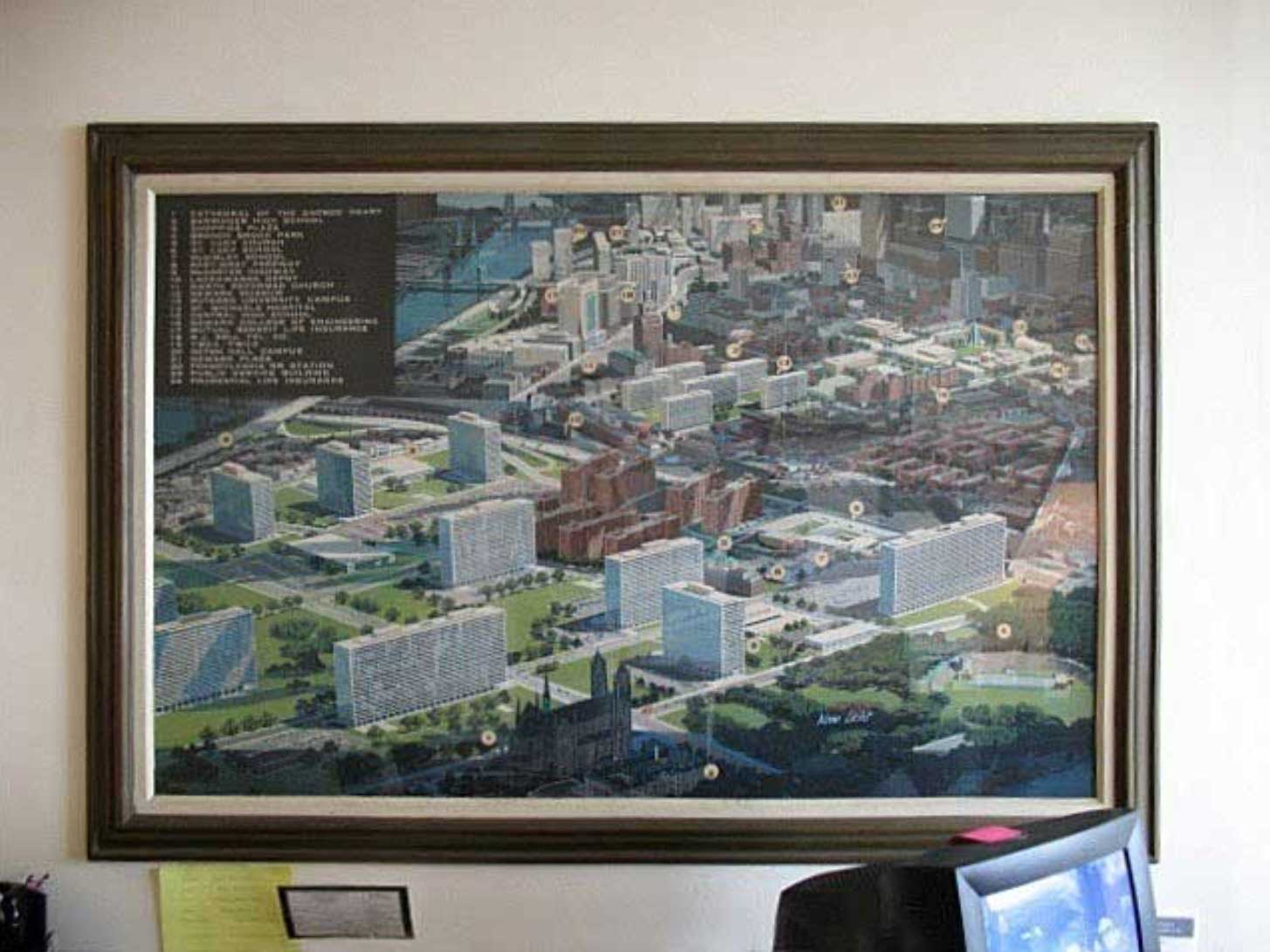

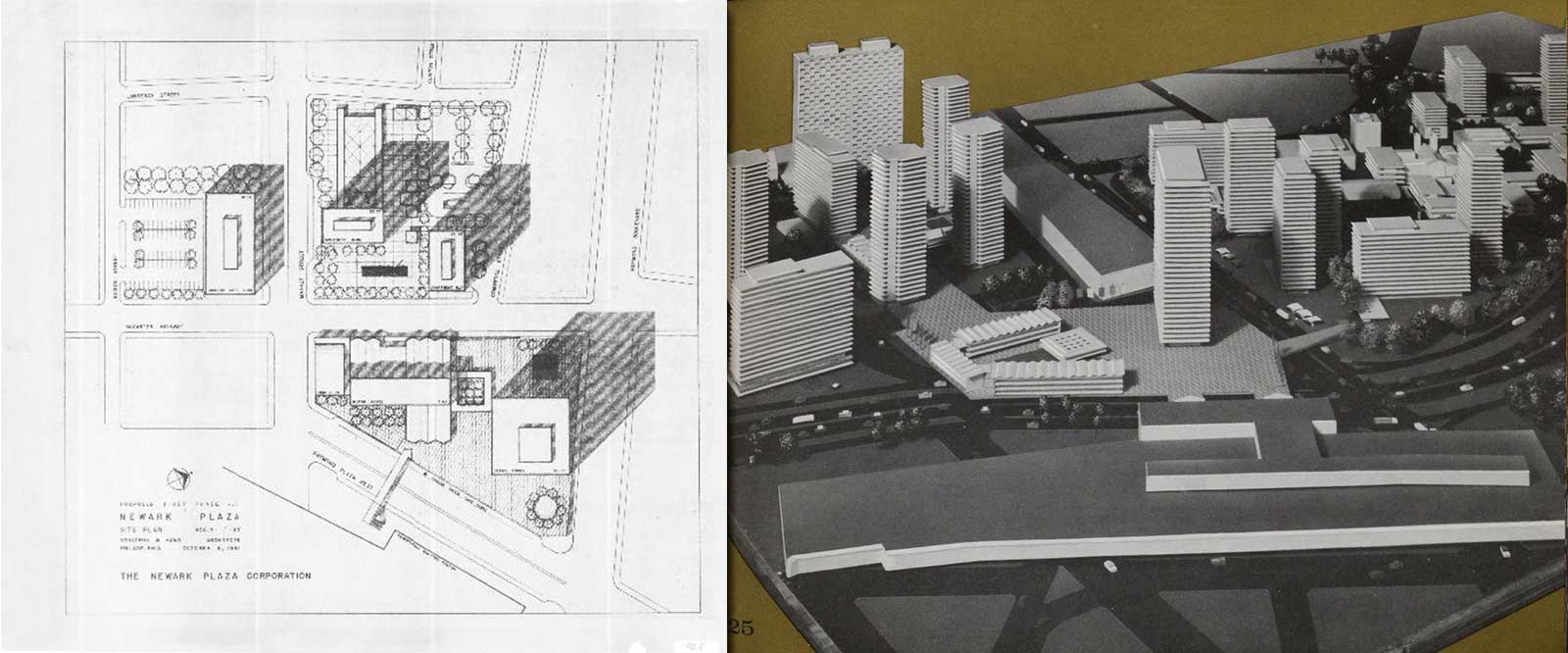

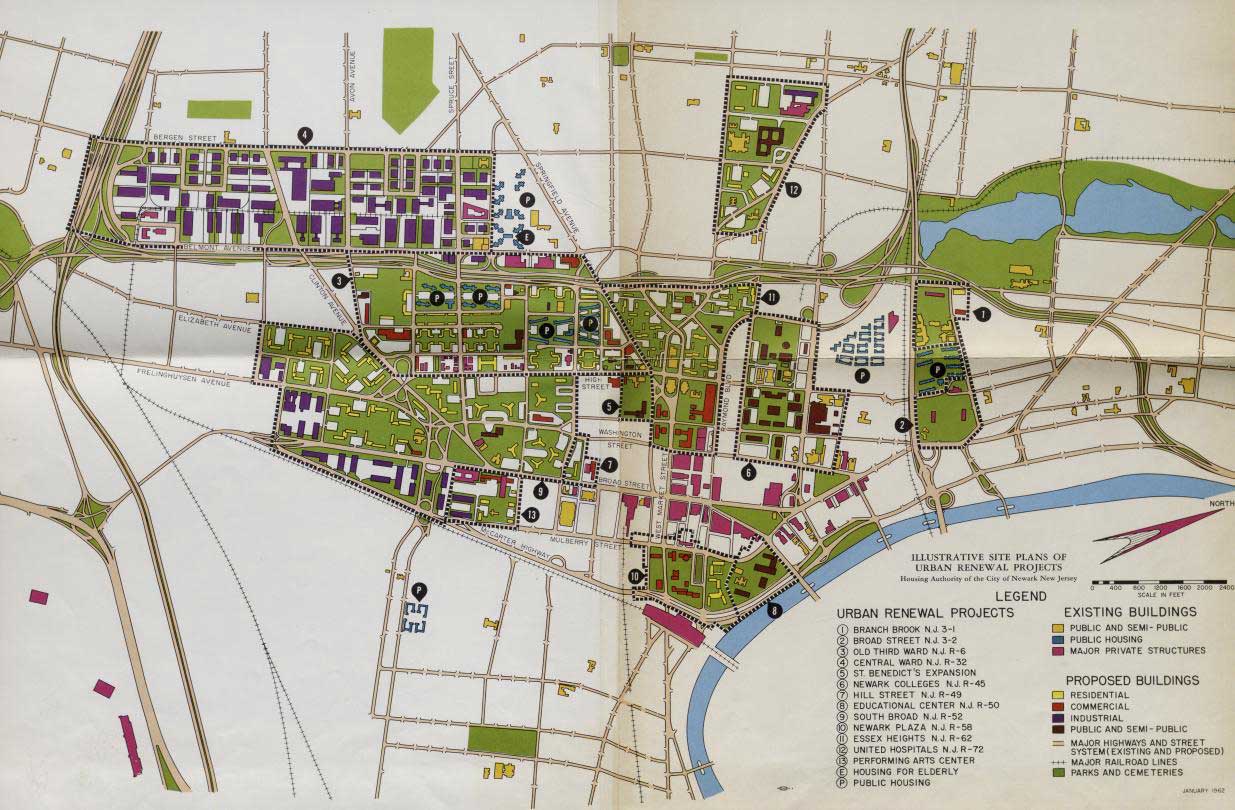

What Newark planners devised was tantamount to a complete reimagining of the city. Squalid tenements were to be razed for monumental new apartment towers. Verdant campuses for higher education and medical institutions were to create bucolic surroundings for healing and learning. Factories caked with soot from decades of industrial output were to be replaced with state-of-the-art facilities interconnected to rail and heavy freight. Gleaming towers of steel and glass would rise heavenward from the heart of downtown. All this investment is glued together by superhighways crisscrossing the city for easy automobile travel. On paper, what the planners believed they were executing were the tenets of a great technological society. They would soon enough realize how mistaken their expectations had become.

Brick City planners began executing their ambitious plans in earnest, some projects advanced along in the early 1950s such as new public housing projects and improved automobile access in the city (by replacing what remained of our trolley lines for buses). But with the Government funds provided to them under the Federal Highway Act in 1956, the highway backbone of this modernist utopia was pushed into overdrive. The planners hoped to encourage motorists from across the state to come enjoy the retail variety and commercial fervor of downtown in the hopes of inspiring further investment and population growth in the city. Then came the Census figures for 1960: Newark’s population had declined by 7.6%, and alarm bells began to ring across City Hall and the business community.

Newarkers still rightly clamored for clean and improved urban spaces, with natural surroundings to live, work, and raise their now-growing families. The projects announced looked promising, but Newark was a city with high taxes, lacking affordable housing for a ballooning Middle-Class populace, and a public transit network that had become more unreliable and chronically held back by the same traffic the planners were trying to induce. Why wait 20 years for the circumstances to improve when you could hop on the Garden State Parkway to your own picket-fence paradise today?

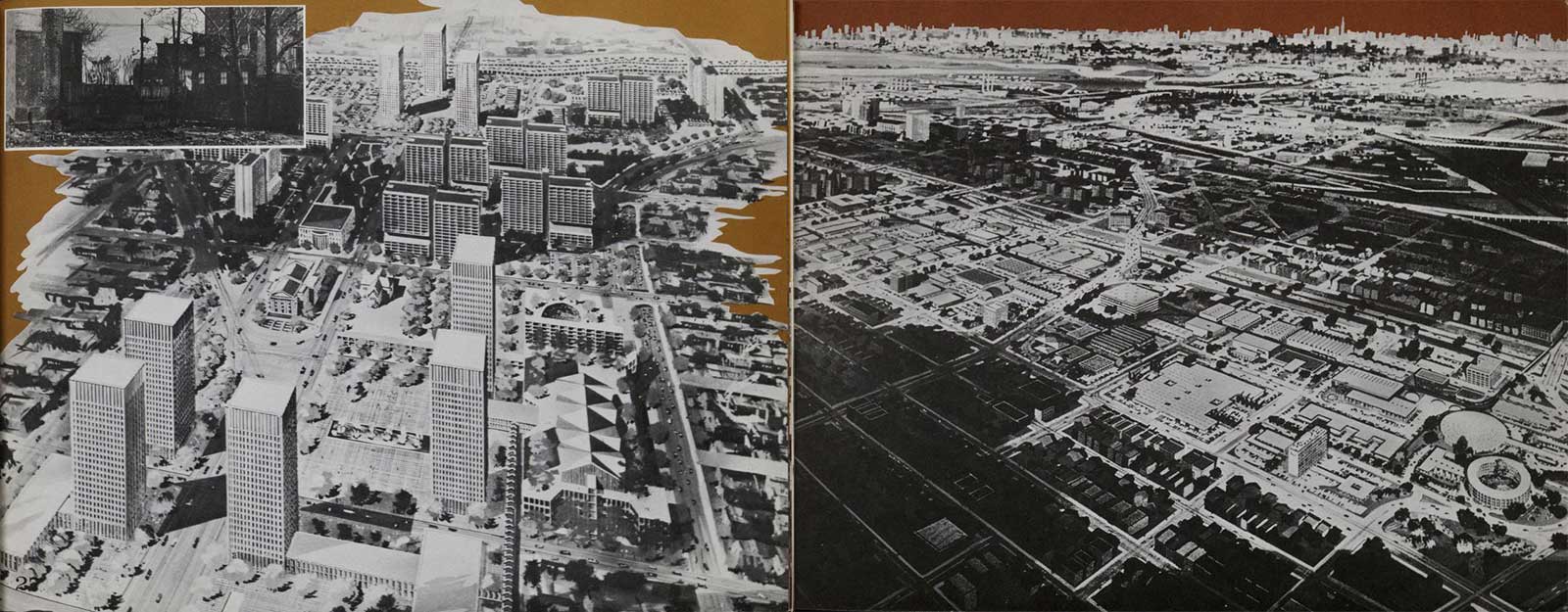

The Federal government threw incentives to help middle-class Newarkers leave for cheap homes off in the rural boondocks and then convinced municipal officials to build the one thing that was working against the City’s own interest. Newark planners did not realize their Motorama backbone was a poison pill and not a panacea, the highways were not bringing wealth into the city, it was draining all its fortunes into the back of the beyond. To stop the further bleeding of residents, and importantly tax revenue, the city had to accelerate their vaunted goals in an even more augmented pace, drastic measures were taken in the name of urban renewal, resulting in catastrophic consequences.

In the span of the mid-century, Newark was being razed to the ground with maniacal abandon. All in the name of once again attempting to create the Metropolis of Tomorrow. Trying to address three centuries of urban dysfunction in two decades had caused city leaders to lose sight of what made Newark a thriving urban center at the onset.

Desperation began to set in, City leadership lived in denial that their own mismanagement and hubris were the cause of this decline… what fomented was the draconian scapegoating of Newark’s remaining citizenry for ‘standing in the way of progress’. Insolence was punished with eminent domain, rightful protest was met with violence, and the message of creating a greener city for all was abused to paint entire communities in red.

Anger and resentment built up like a pressure cooker to the point it finally burst in 1967 with the Newark riots, a half-century of municipal ineptitude, corruption and cultural bile was reduced to one sweltering summer day in July. The Brick City bent over backward to battle societal forces that were naively misjudged and impossible to overcome.

The 1970s proved to be unkind years to Newark and the Country at large. Once again, the projects that could proceed with their construction did so, but heavily revised to meet a now uncertain future. Gone were the crystalline spires set in parkland, now they were brutalist fortresses surrounded by impenetrable walls and laden with security cameras. Gone were the promises of a peaceful, technocratic city built for all, here was now a rifted city built on fear and disillusionment. Harper’s Magazine did not mince words when in 1975, Newark was declared ‘The Worst American City’, a title that no Newarker at the beginning of the 20th Century would have ever conceived to be bestowed upon their fair city.

Twenty years after the death of our mid-century delirium, the streets of Newark were once again ignited by the promise of better times ahead, infected by the pungent odor of corporate speculation and the sight of slick-haired charlatans in pin-striped suits. They peddled trickle-down potions of how to Make Newark Great Again, and we continue to fall for their sweet-smelling traps, as we progress through the 21st Century.

Stay tuned for our final installment in ‘The Newark that Could Have Been… Part III”