Guest Post by R. Ballantine

Newark’s Gilded Age created a group of families that together helped build this city into an industrial powerhouse. These families also left a legacy of beautiful and stately piles that showed their owner’s wealth and status. Some were lost to the ages, others donated to posterity, and as of the Kruger-Scott Mansion, saved from near ruin. When you walk by the Newark Museum today, you see another of our great houses shielded behind a cube of white film, being lovingly restored by its cultural patron.

When you walk through the leafy streets of Forest Hill, you see the second generation of these great houses. Proud of their eclecticism and style, these houses hold no shame in their front lawns and porte-cocheres. At the turn of the century, to be wealthy was not just to have an opulent house, but to have a lot big enough to appreciate it from the street. They emerged in a time when owning an automobile was a luxury, and to be surrounded by nature and be within city limits was a bragging right. Newark today still holds these houses in high regard, and stand ensured that they are protected from the ravages of time and development’s bad actors. These houses are held up on a pedestal… much to the detriment of the rest of Newark’s Residential Heritage.

Newark was not a city just for the rich and powerful… It was a city of proud clerks, doctors, butchers, bakers, union laborers, and market speculators. They each contributed to creating houses that were eclectic and brimming with architectural flourish. When you are proud of where you live, you tend to put more effort to curb appeal than any curmudgeon landlord. You look at your modest budget and tell your builder “Make my house pop!”. You look through photographs from a century ago and you see charming Victorian and Queen Anne houses, with neo-classical porches and tall turrets, topped with copper finials. Elaborate brickwork when a carved stone was too expensive, and colored stucco just to match the brownstones up the street. These houses competed with charm, form, and color. You might not have the means to compete with the Clark’s or Krueger’s, but you sure as hell could show off your house to your coworkers as the streetcar passed by on your way to work.

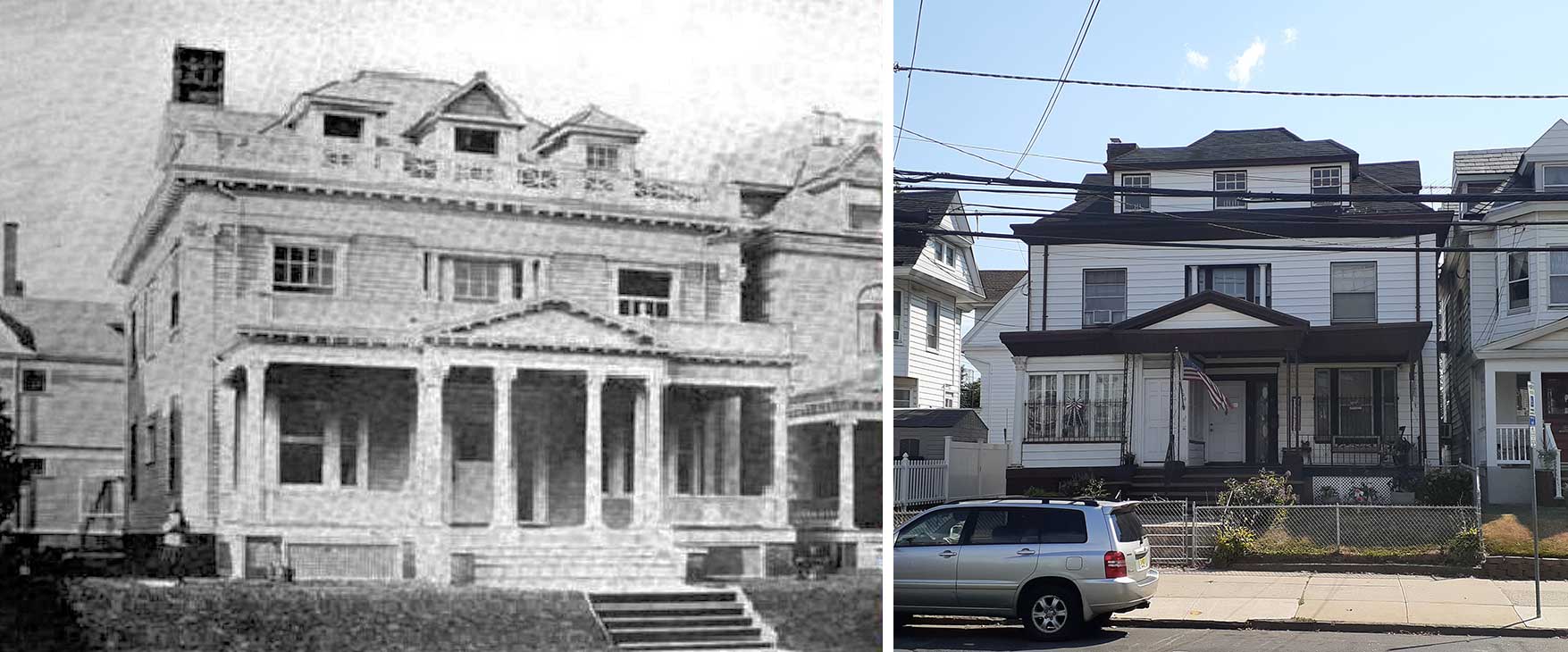

This beauty is now hidden by layers of vinyl and asphalt shingles. Newark became a victim of a mid-century push for concealing and removing what was seen as frivolous embellishments. Newarkers chose to cover up this charm and individuality behind mass-produced facades. Beautiful Victorian homes became clad in the ill-fitting garb of the suburbs, making the residential neighborhoods of our city far uglier places to call one’s own. This only gives license to outsiders to view these houses clad in petrochemicals as eyesores to be replaced by cheaply built, fake modern developments, or worst of all, Bayonne Boxes. Social Media is littered with images of people finding gems behind the vinyl and returning old houses to the jewel boxes they once were. San Francisco leads the nation in obsessively reproducing neighborhoods ravaged by the aesthetic crimes of past generations.

Sadly, those with the means to restore these neighborhoods are the ones who don’t live in these houses. Forest Hill and Weequahic have the luxury of communities that can afford the expense of preserving their neighborhood’s charms and legislate for their protection. Where are the people advocating to restore Roseville and Mount Pleasant?

Newark could have the prettiest neighborhoods in America… but only if we gave the humble rowhouses on Summer Avenue the same dignity to be saved as the greatest mansions on Ballantine Parkway.