An urban planner has an idea to create a massive circular rail track connecting New Jersey’s three largest cities —Newark, Jersey City, and Paterson. Christopher Kok’s plan relies on using the existing Hudson-Bergen Light Rail and the Newark City Subway while cobbling together underutilized and abandoned freight lines.

“It’s just a matter of piecing together the pieces that are already there,” Kok told Jersey Digs.

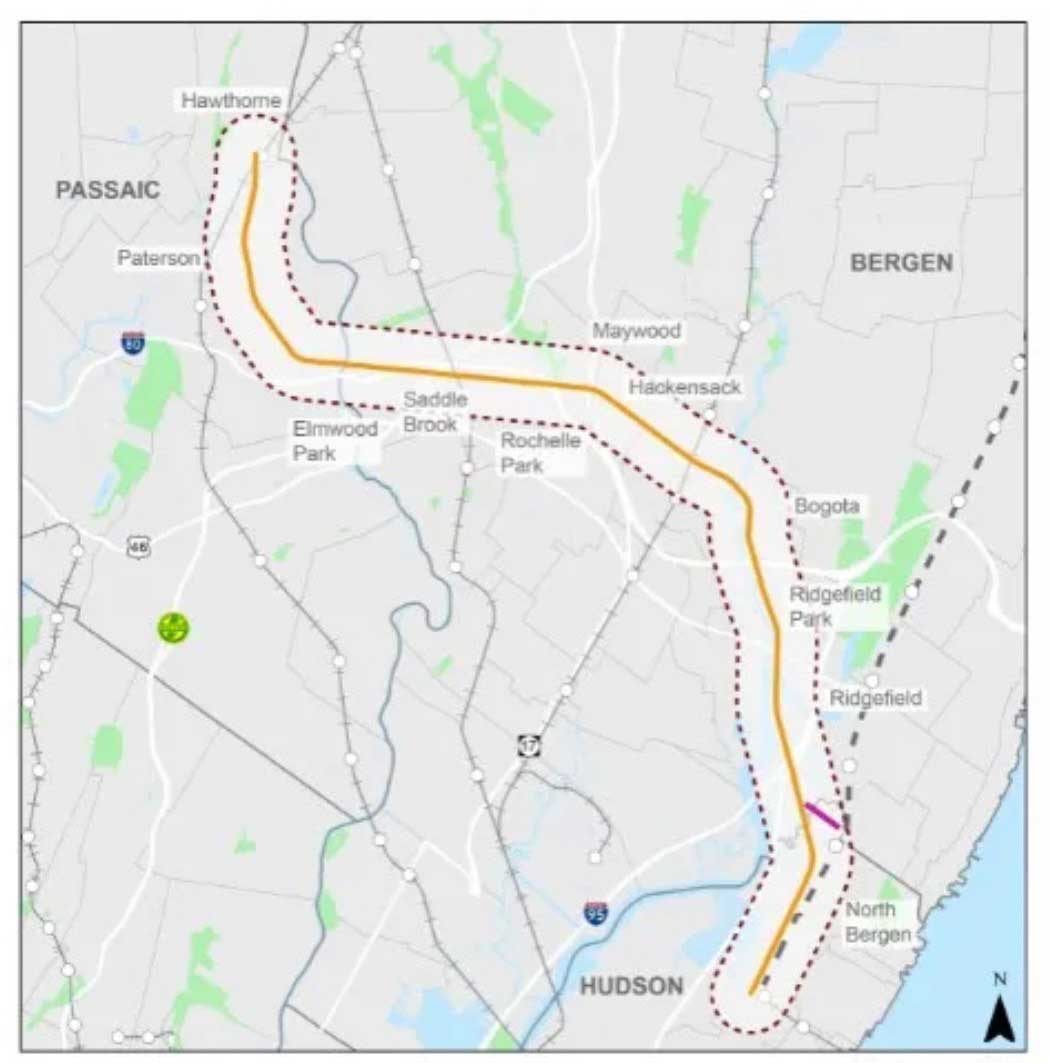

Today, the northernmost stop on the Hudson-Bergen Light Rail is in North Bergen. Kok wants to extend that line to Paterson using a lightly used freight track called the New York, Susquehanna and Western Railway (NYS&W) corridor. In 2021, NJ Transit gave a presentation on the possibility of extending the line into Passaic County. “They’ve been trying to push that for a few decades but it hasn’t gotten anywhere yet,” Kok said.

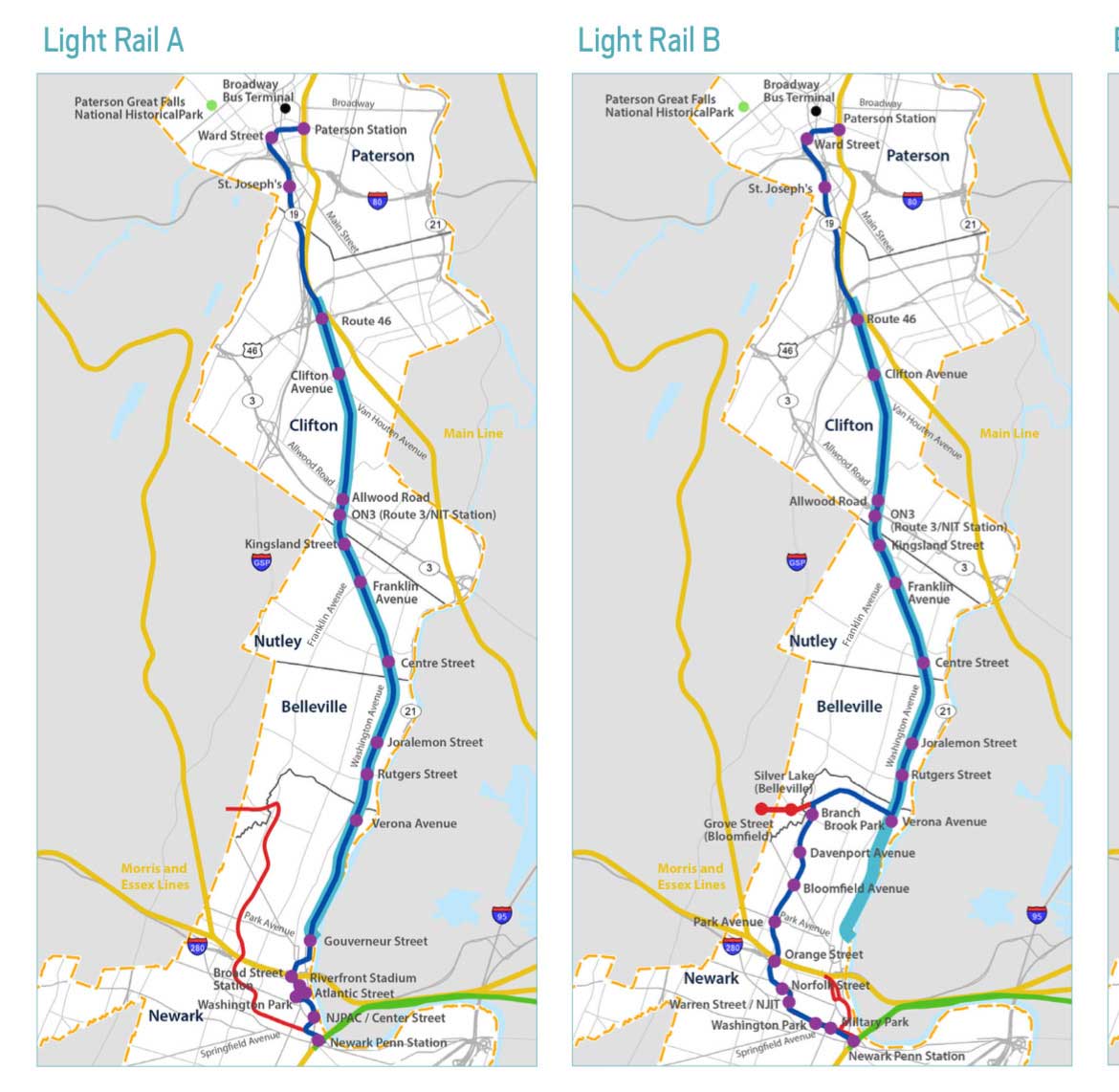

From there, Paterson could be hooked up to the Newark City Subway using the abandoned Boonton Line. Paterson Mayor Andre Sayegh has thrown his support behind the plan. “With President Biden emphasizing infrastructure improvements, I feel like the time is right,” Sayegh told NorthJersey.com. “The stars are aligned.”

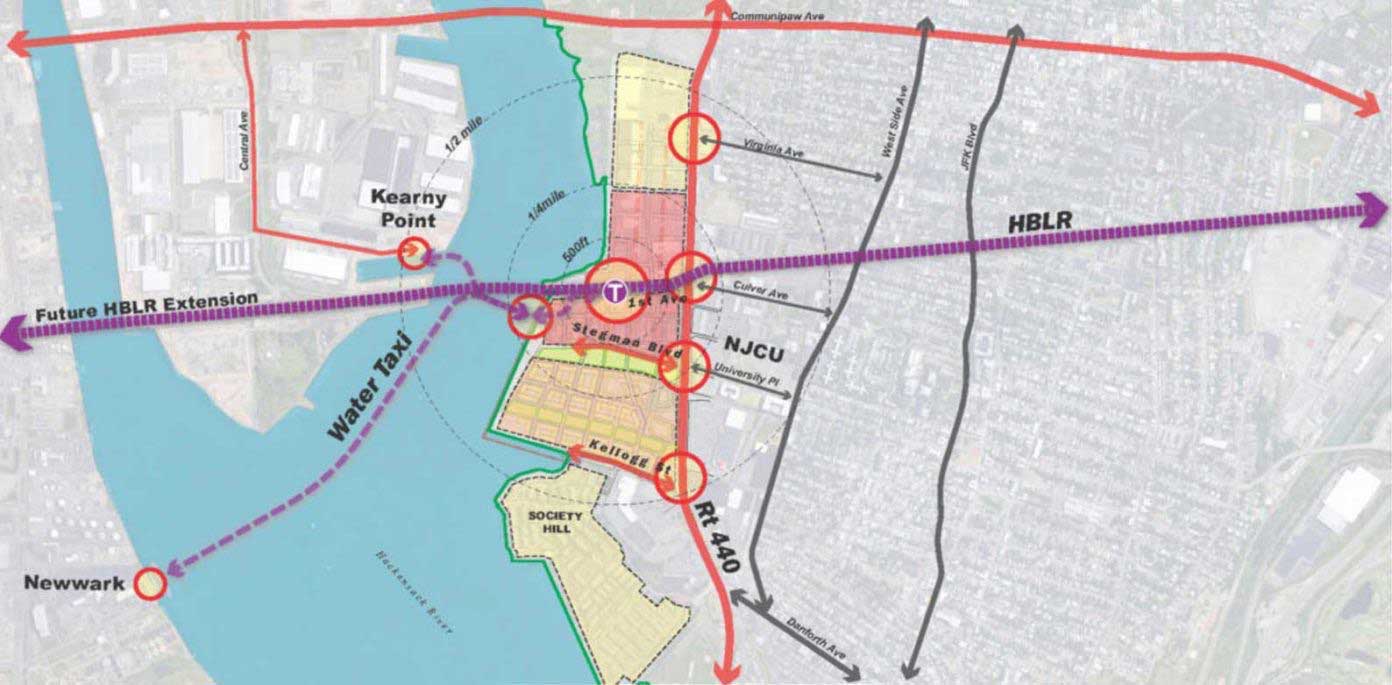

The last leg of the 30-mile circular track would connect Newark to Jersey City by restoring the old Central Railroad track. This passenger line used to travel from Broad Street to the Communipaw Terminal in Jersey City from 1869 to 1946. The old terminus on Broad Street still exists. Part of the right-of-way was lost to development, but a sliver still exists between Newark’s Ironbound neighborhood and Jersey City.

In fact, when Jersey City announced its long-term plan to redevelop the bayfront along the Hackensack River, it also mentioned the possibility of extending the light rail into Kearny Point, then perhaps further to Newark’s East Ward.

The end of the 19th century gave rise to a street car boom that allowed cities to develop into the surrounding farmland and forests. In a matter of two decades, Newark, a city that hugged the bend of the Passaic River for most of its history, developed suburbs like Roseville, Clinton Hill, and Weequahic, according to Steve Elliott, a history professor at Rutgers University-Newark, who have gave a presentation last week at Newark History Society called “Building Newark’s Streetcar Suburbs.”

The demise of that extensive street car network began in the 1930s largely because of the automobile, which allowed Newarkers to build new homes in suburbs like Maplewood. “Technology conspired against the streetcar suburbs,” Elliott said.

Kok believes city planning based around the automobile has reached a breaking point, and the growth of the state’s largest cities depends on reclaiming the region’s abandoned rail lines for light rail. “Any further development based around cars doesn’t make sense,” Kok said. “The geometry doesn’t work.”