The battle to save Newark’s James Street Historic District, after decades of encroachment, has reached a moment of truth.

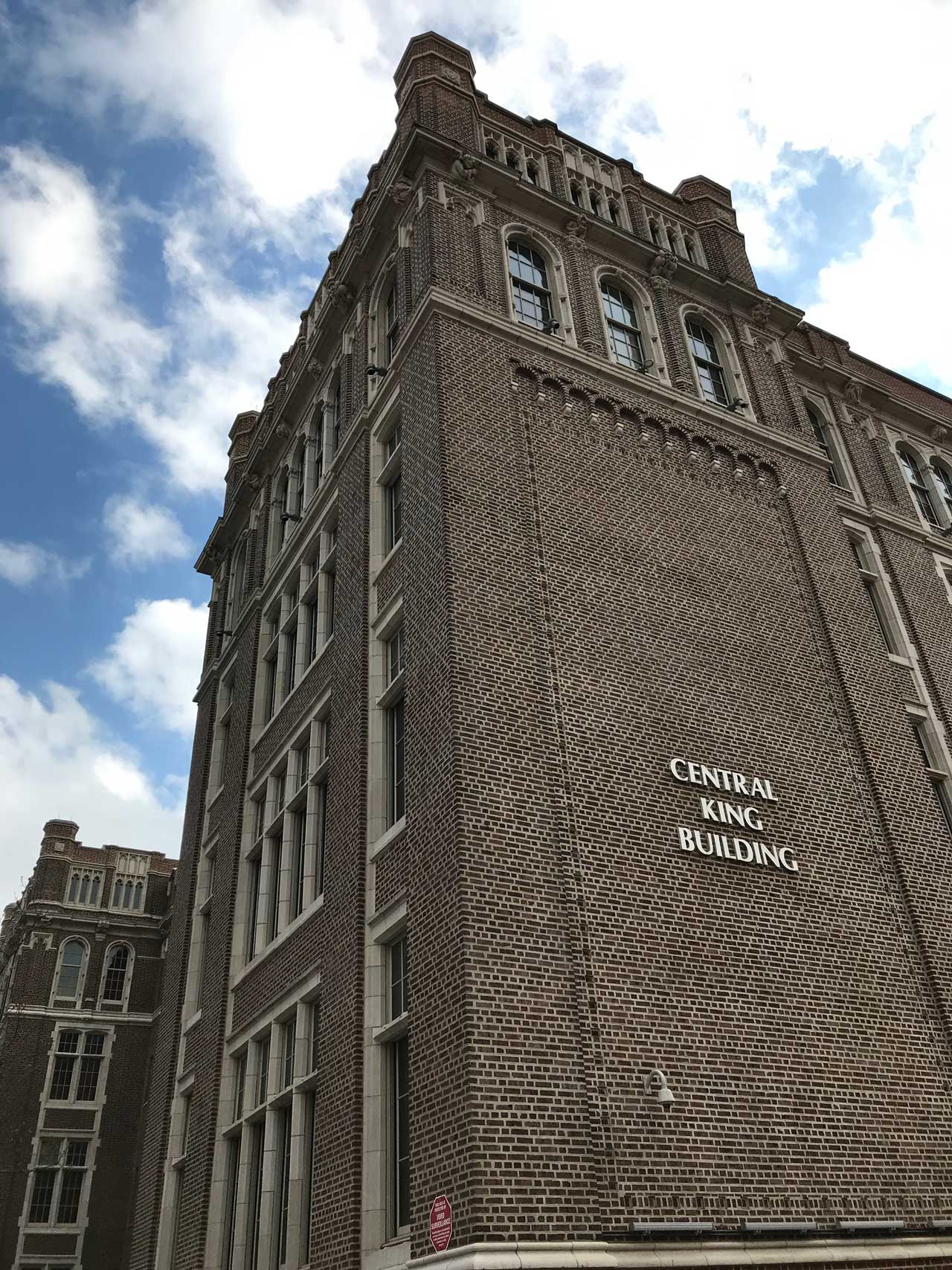

In a series of rulings delivered last month, the State Historic Preservation Office denied New Jersey Institute of Technology’s application to demolish four buildings within the city’s first and oldest historic district.

The denial, however, is only conditional, meaning the university must come before the review board again to share details of its redevelopment plan, called the NJIT Campus Gateway MLK Project.

“I understand that to move forward the university has to develop,” said Zemin Zhang, a James Street resident and executive director of Newark Landmarks. “But my purpose is to press NJIT to adopt a different attitude.”

Zhang believes that a motivating force behind NJIT’s redevelopment plans is an effort to forestall a looming crisis in higher education that experts are calling a “demographic cliff,” in which enrollment is expected to drop.

Unfortunately, the university has demonstrated a pattern of behavior that predates this recent hearing, as Jersey Digs reported, and seems to treat historic buildings as an impediment to its own progress.

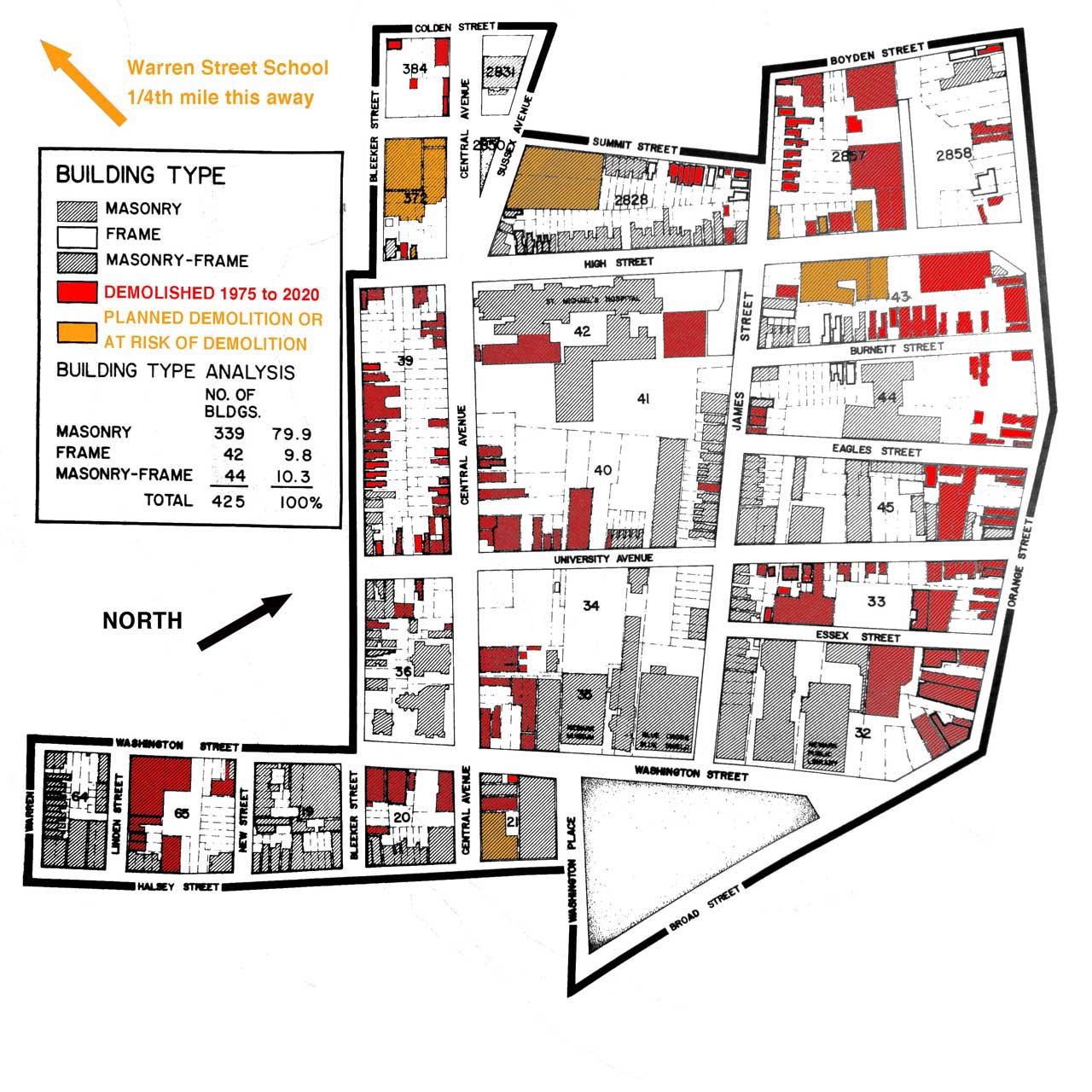

In the past application alone, the university sought to raze six buildings in the historic district: 238, 240, 250, 317 MLK Boulevard were all spared temporarily, while two buildings that comprise the Mueller Brothers Florist factory were authorized for demolition.

Despite the loss of the factory, which some thought was worth saving, leaders in the preservation community believe the ruling gives an opportunity for NJIT to align its goals with the rest of the neighborhood.

“The district is under pressure and so much of it intersects with NJIT,” said Emily Manz, executive director of Preservation New Jersey. “We need to see their plans in a more holistic sense, so that it can be planned out in partnership with the community.”

Manz — who confirmed that the James Street Historic District has been nominated for her organization’s annual Most Endangered Places list — notes that the SHPO hearing is a chance to find common ground.

“Preservation advocates are walking in lockstep with the goals of NJIT and they need to be included in the future,” Manz said.

Not everyone, though, shared in this spirit of optimism.

“If we don’t do something, there aren’t going to be any buildings left in the historic district to call it a historic district,” said Guy Sterling, a James Street resident since 1986.

Understanding Sterling’s weariness requires some knowledge of Newark’s past. The local historic preservation movement began with the James Street Historic District in the late 1970s. For such an old city that lost many landmarks to urban renewal, that was a late beginning.

Newark didn’t have a so-called Penn Station moment like New York City had. It wasn’t the loss of a particular landmark that galvanized the preservation community to lobby for legislative guardrails. It was a death by a thousand cuts that inspired Donald Dust, founder of Newark Landmarks, to push for a place on the National Register of Historic Places.

“There was no singular moment, but there was a singular person,” Sterling said.

The recognition of the James Street Commons was meant as a defense against demolition, but far too many developers have been able to storm these legal ramparts. Since 1975, about 190 buildings — or about 45 percent of the neighborhood — have been lost. Among the buildings gone forever were homes with rare architectural features like the Lloyd Houses, which Sterling calls the last and best example of Federal-style architecture in Newark.

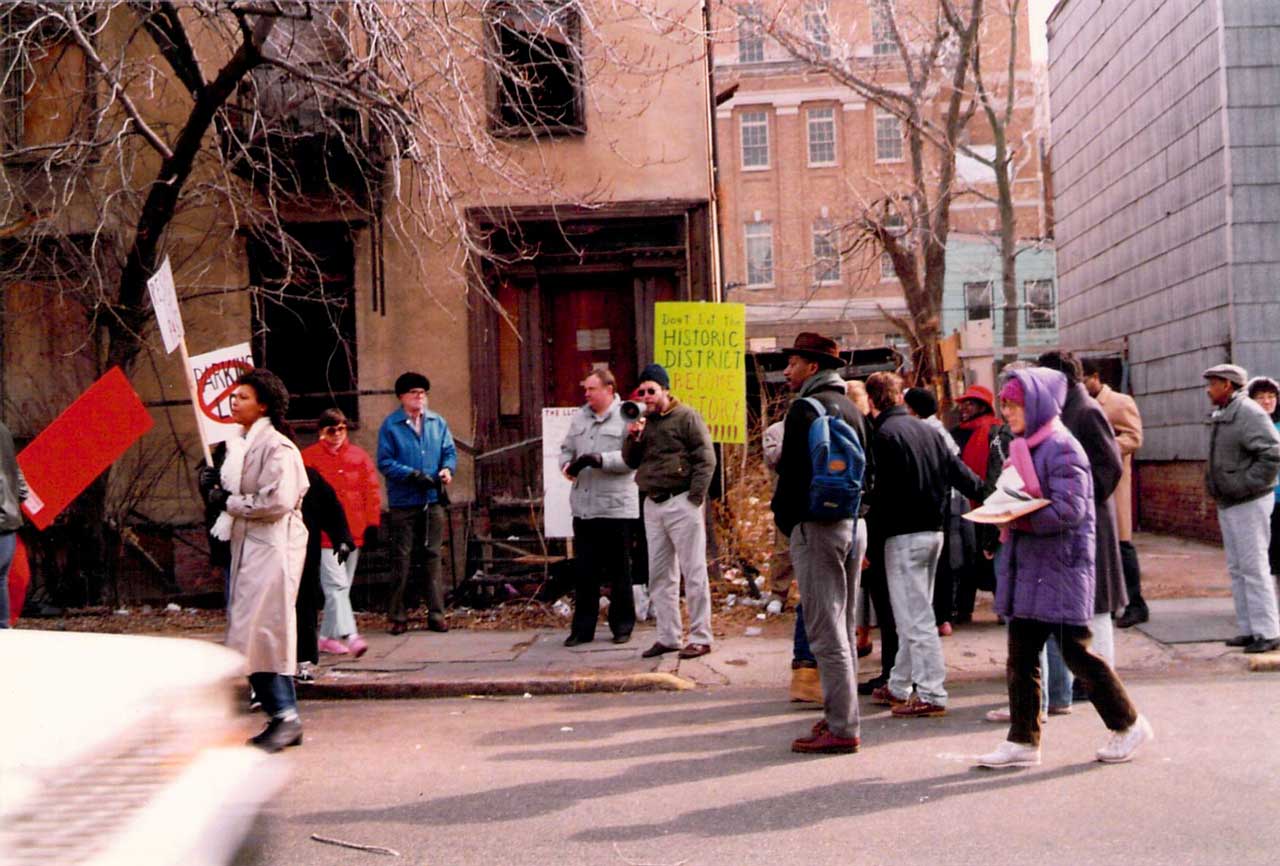

In fact, Sterling organized a protest in the late 1980s against the developer who had promised to restore the Lloyd Houses, only to neglect them, then ask the city for permission to bulldoze them. Today, they are a parking lot.

“That was an eye-opener to me,” said Sterling, a former reporter for the Star-Ledger, “that developers weren’t interested in following through on any promise to keep historic buildings standing.”