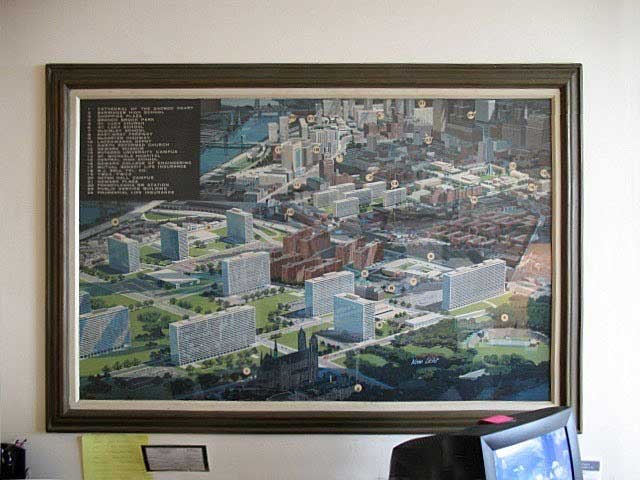

It’s been fifty years since Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s death and the details of his international career have been carefully archived. But a mysterious painting has surfaced that reveals what may be an early version of his master plan in Newark.

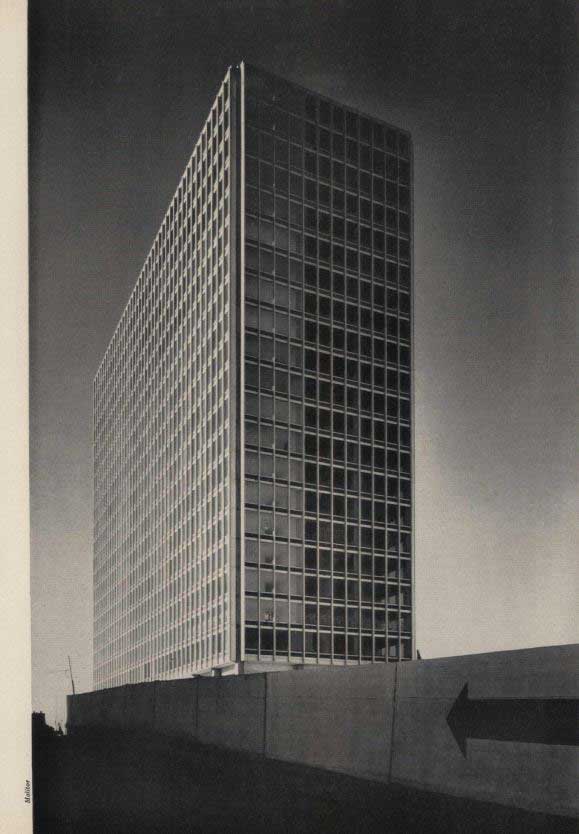

In 1957, the famous Modernist architect designed three glass towers in Newark that were the height of style and technology. The Colonnade, Pavilion North, and Pavilion South were supposed to lure back middle-class residents who were leaving the city and its aging infrastructure for the suburbs.

The artwork, which appears briefly in a somewhat obscure documentary by Austrian filmmaker Heidrun Holzfeind, depicts a far more ambitious vision where seven towers — instead of three — rise out of parkland that stretches from Branch Brook Park to the edge of the Passaic River, then north beyond 6th Avenue.

“Mies wanted to bring his vision of a minimalist city, a modernist city, to Newark just like he was doing in Detroit,” said Gabriel Dal’Maso, a Newark-based architect, who spotted the painting in the documentary. “It gives credence to the painting I found. Could it be a master plan that tried to replicate Lafayette Park?”

Dal’Maso’s attempt to decrypt the painting began a few years ago when a developer proposed a building on a long-abandoned plot of land between the Pavilion towers. In protest of the new development, Dal’Maso, who was living in the Pavilion at the time, gave a public comment at a city council meeting. Preparing for his testimony, he pored through research materials and amassed a trove of historical documents about the glass-and-aluminum towers.

“Modernists had a quasi-utopian belief that by creating a city that was friendlier to its citizens, we could create a better society,” Dal’Maso said. “I wanted to protect the integrity of that vision.”

Modernist architecture has always struggled for acceptance. In the 1960s, when brash new designs challenged Gilded Age aesthetics, critics were appalled. George Wilson, a journalist for The Evening Star, wrote that the Modernist buildings were like “putting a mustache on the Mona Lisa.” The fight to protect these mid-century structures never ends. In April, Jersey Digs reported on the battle to save Trenton’s Health & Agriculture Buildings, which were demolished after publication.

Despite the importance of the Modernists and the role these buildings play in the history of urban renewal, Colonnade Park, the collective name for the three towers, isn’t protected by a landmark designation, despite an attempt by a local preservationist, Zemin Zhang, to nominate it. The owner wouldn’t consent to the designation, so his effort was in vain.

As for the painting, Zhang agrees it is an early rendering of Colonnade Park. The developer, Herbert Greenwald, originally wanted eight acres of land, which the county refused to grant him, Zhang noted.

“With all the restrictions, including the timing, they settled on four towers which later became three,” said Zhang, executive director of Newark Landmarks.

Greenwald, who was Mies’ longtime collaborator, was killed in a plane crash before the Colonnade opened in 1960. The reins were taken over by a new developer, Bernard Weissbourd, who seemed to briefly rekindle hope of expanding the development. A Newark Evening News article from 1964 mentions a proposal by Metropolitan Structures, Weissbourd’s firm, for a nine-block addition to Colonnade Park. But then the trail goes cold.

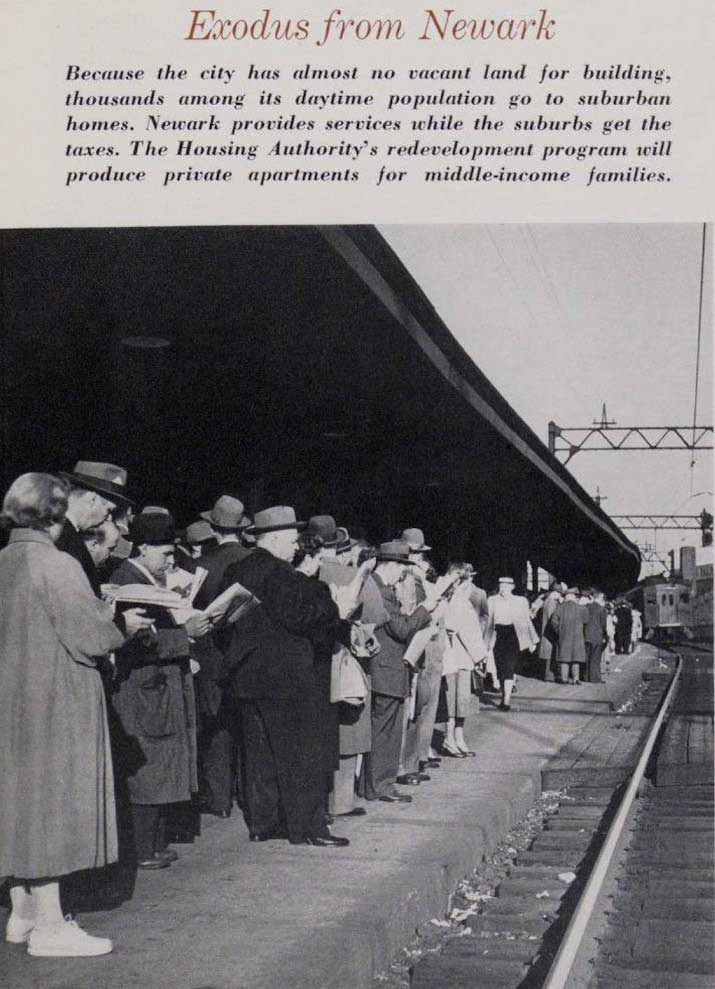

A possible explanation why the other towers were never built was because Mies’ city-within-a-city never delivered on its promise to keep the middle class in Newark. At first, the solution was to dazzle residents of the Colonnade and Pavilion with the sort of white-glove service reserved for fine hotels. Babysitters, dog-walkers, barbers, and masseuses were all services offered there. If a tenant had an overnight guest, a bellhop would wheel a cot up to their apartment.

But no matter what length the staff went to, nothing could stop the social forces of suburbanization. People often say the riots in 1968 caused Newark’s decline, but the riots only hastened what was probably inevitable. Louis Danzig, then the director of the Newark Housing Authority, became a scapegoat for the failure of urban renewal.

“After the Newark Rebellion, the urban renewal process collapsed,” Zhang said. “Danzig became like a criminal.”

Meanwhile, a new proposal for a five-story residential development in the abandoned lot between the two Pavilion towers could soon come before the city council. The developers will surely clash with the guardians of Mies’ vision.

“If Mies were still alive he would think, ‘My goodness, you put this next to my building?’” Zhang said.

As for the painting in the documentary, which debuted ten years ago, no one seems to know what became of it. The management at both the Colonnade and Pavilion buildings told Jersey Digs that they’ve never seen it.