As the nation braces for a “dark winter” of coronavirus, remember that our predecessors survived much worse.

Life in the early 1900s was full of hardship. Mrs. Barrett, a South Orange resident, nearly lost her entire family to disease. First, her husband died of pneumonia in 1907. Then four years later, three of her children caught diphtheria while swimming in a New Haven lake. Her seven-year-old daughter would end up dying of the infection.

Pneumonia, diphtheria, scarlet fever, the measles — these were only some of the ways you could die of sickness in the old days. There was also typhoid fever, tuberculosis, smallpox, spinal meningitis, cholera, the Spanish flu, and polio.

“Rates of infectious disease were astronomically higher just a hundred years ago. This was just something that was priced into people’s daily routine,” said Brian Daniels, biology professor at Rutgers University. “But now with coronavirus, we’re getting a taste of what it used to be like.”

The first epidemic in the United States was yellow fever in the 19th century. This was before scientists understood how diseases spread. It seemed like a terrible coincidence that dockworkers kept getting sick until we figured out that mosquitos, which lay eggs at the water’s edge, can carry the disease. In fact, the best doctor of that era, Alexander Anderson from Bellevue Hospital, couldn’t save his own wife, son, mother or brother — they all died from yellow fever.

Early health officials compensated for limited know-how with strict quarantines that many today would find objectionable. Alfred Schmock from South Orange was diagnosed with scarlet fever, but decided to leave his house to get a second opinion. He was arrested. Mrs. Mendel from Maplewood was taken to court for failing to notify the health department that three of her children had the measles. Police held up a train at South Orange station to apprehend passenger Rubino Lubiano, who had broken quarantine after being diagnosed with scarlet fever.

And Thomas Hudson, a student at Park Avenue Elementary School in Orange, was diagnosed with scarlet fever by a school nurse. He was rushed off in an ambulance before his parents were notified and was brought to the infamous Isolation Hospital in Belleville.

In the late 19th century, germ theory was discovered. But this knowledge was limited to academic circles and really didn’t affect public-health policies for decades to come, Daniels explained.

It was much harder in the old days to inform the public how to stay safe. Today, health information comes to us instantly through the screens of our phones. In 1911, the Anti-Tuberculosis League held exhibitions on Main Street in Orange to spread awareness and even named Oct. 27 Tuberculosis Day.

The reason for so much sickness was because most people were living in a sanitation nightmare. Tenement houses lacked ventilation. Industrial workers labored in crowded warehouses. Garbage collection by “scavengers” was spotty, so vermin had a buffet.

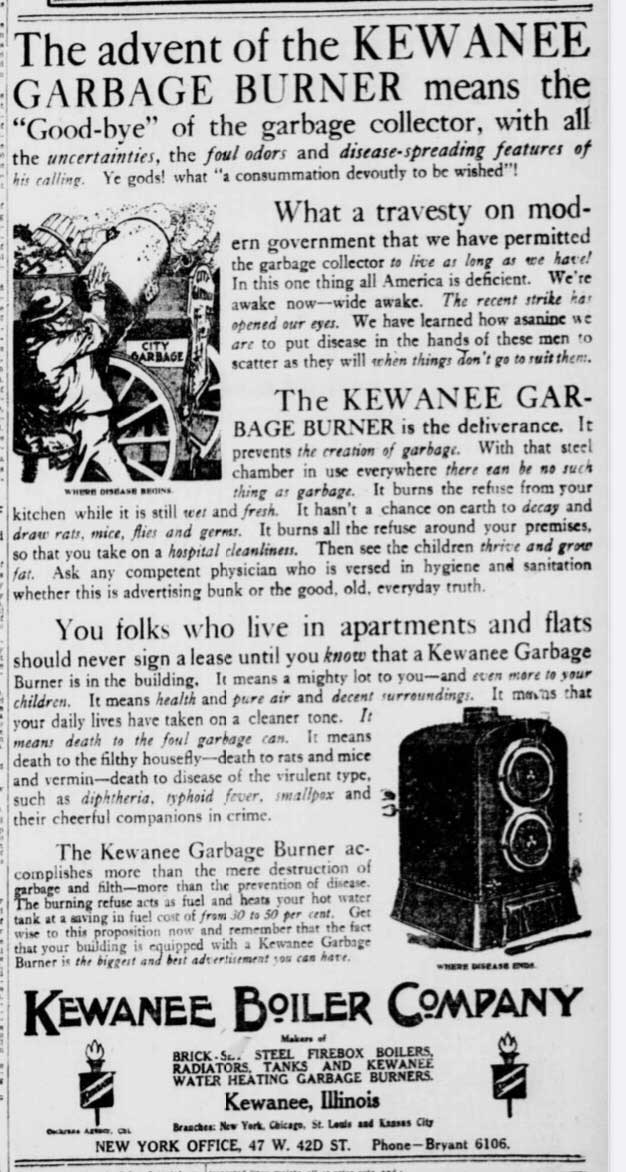

In the New York Tribune from 1911 the Kewanee Boiler Company advertised a metal receptacle to burn garbage in, which had the dual function, it claimed, of saving people from diseases and heating water. At the end of a long day, who doesn’t enjoy a warm bath heated by a pile of burning trash?

Water, as the Barrett family found out, was a major breeding ground for pests and diseases. Fatal typhoid outbreaks ravaged 50 people in Montclair in 1894, then 73 more in 1914 at St. Anthony’s Orphan Asylum in Newark because of dirty wells. In the Oranges, the reservoir at Campbell’s Pond was finally filtrated in 1908. That same year, the Orange Board of Health began pouring petroleum into sewers to kill mosquitos, which made its way into the rivers along with other raw sewage.

Perhaps the infection most similar to the coronavirus, in terms of who it affected and how severely, was tuberculosis. Also called phthisis, consumption, and the white plague, it attacks the respiratory system and is somewhat unpredictable: some people recover quickly, others die from gruesome complications. And just as we see that the coronavirus disproportionately affects certain demographics, the spread of tuberculosis is largely determined by social and environmental factors. It is still a health concern in Africa and Asia.

Tuberculosis is particularly dangerous because it can taint the food supply, including through the dairy industry. The Newark Evening Star reported that in 1913, East Orange alone drank 15,000 quarts of milk each day, so there was huge risk for outbreaks. Things got ugly at the Fairfield Dairy Company in Montclair, where the Tuberculosis Cattle Commission found 126 positive cows.

In the mid-20th century, widespread vaccination, improved housing, decreased urbanization, and wastewater management drastically reduced the rates of infection in the United States, according to Daniels. But there was a tradeoff: pandemics are fewer now but they spread far more quickly than before. In the Middle Ages it took decades for the Bubonic Plague to spread from Asia to Europe. The coronavirus went global in a matter of months.

“Our increasing connectedness has made control harder,” said Daniels, who has co-authored several papers on West Nile virus. “We tend to think that modernity has increased our safety, but there are ways that it increases our risk as well.”

Still, there is something worthwhile to learn from studying the past. At the current exhibition on epidemics at the Museum of Early Trades & Crafts in Madison, you can find newspapers articles, personal letters, and diary entries by people witnessing outbreaks in the 18th and 19th century. Despite the many years between us and the people who wrote them, the sentiments are oddly familiar.

“Everyone’s saying pretty much the same thing about how these outbreaks were affecting them,” said Shelley Cathcart, the museum curator. “We’ve been through epidemics before — we’ll make it through this one, too.”

Related:

- Beloved Newark Chorus Finds New Home in Historic Schoolhouse

- As Construction Boom Continues, Social Media Influencers are Becoming Preservationists

- Kastner Descendant Dreams of New Life for Historic Newark Mansion