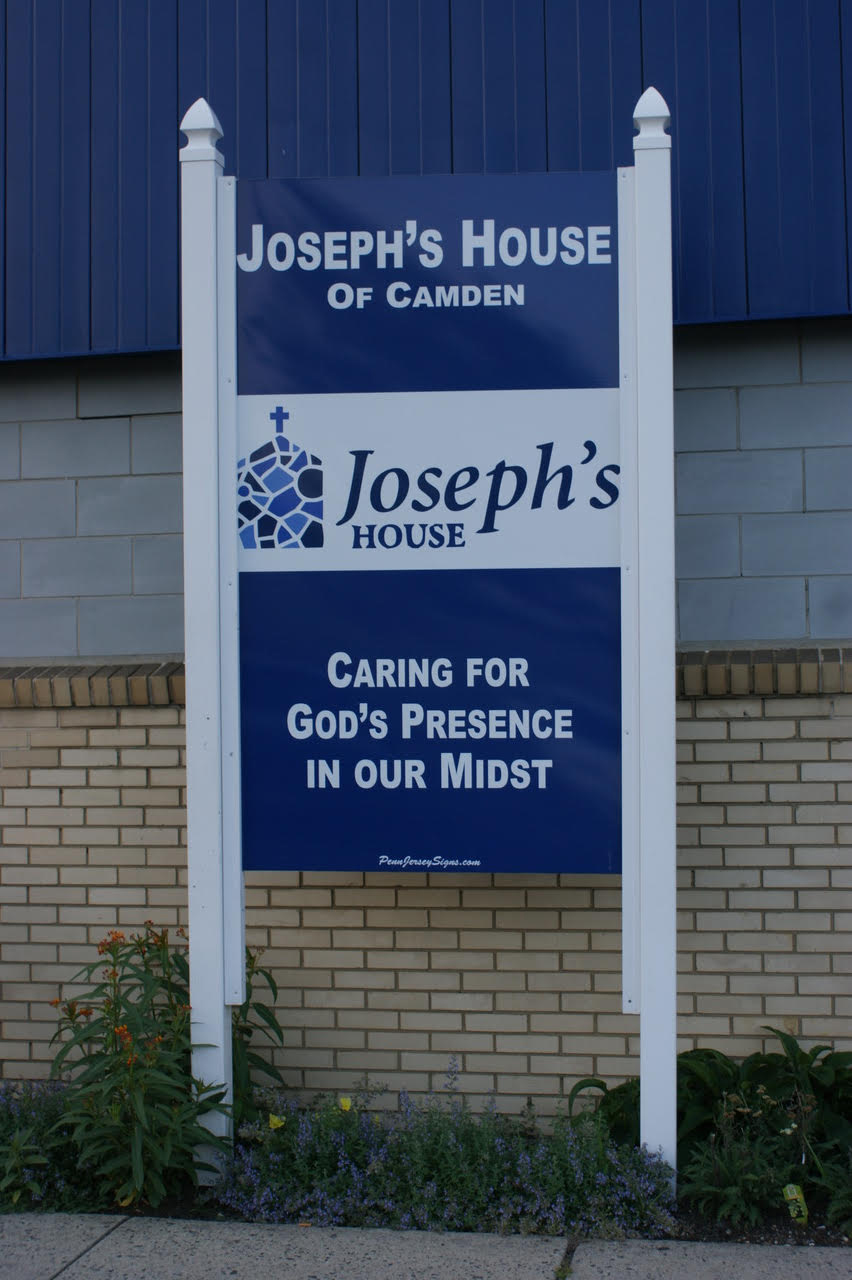

A hot shower. A load of clean laundry. A sit-down meal. At Joseph’s House, a 75-bed homeless shelter and daytime “café” founded in 2010 in Camden, residents can access the basics that most of us take for granted. But beyond these, Joseph’s House invites a closer look thanks to its unique philosophy that puts the individual and his or her specific needs at the center of the process. The opposite of one-size-fits all, it’s a layered approach that may strike some as unorthodox, but a definitive example of quality over quantity.

For starters, not all homeless folks who arrive at Joseph’s House are admitted as clients. While most shelters operate on a first-come, first-served basis, “We really do target the chronically homeless, the hardest to reach. That’s where we go,” Executive Director John Klein said in a phone interview with Jersey Digs.

“Chronic homelessness” is determined by the Department of Housing and Urban Development, but the criteria are steep and ever-evolving. Currently, an individual or family must meet a set of rules, including having resided “in a place not meant for human habitation” for “at least one year or four or more times in the last three years.” Also necessary is a diagnosis of substance abuse disorder, serious mental illness, developmental disability, or chronic physical illness or disability.

Although Klein confirmed that Joseph’s House, which receives both private and public funding, is secular, inclusive, and open to all — “We never ask about your religion, background, or sexual orientation,” he told Jersey Digs — he added that the agency “has a Catholic presence.” For the founders and staff of Joseph’s House, that’s where the focus on chronic homelessness comes in. “There is a tenet [in Catholic Scripture] that says you give preference to those most in need,” he said.

The level of need is determined by a standardized assessment tool that is the accepted gold standard in the field of homelessness services — insofar as a standardized anything can capture the full portrait of a human being’s experience. According to Klein, Camden County was an early adopter of the assessment tool, which is now widely utilized by service providers in neighboring Gloucester and Cumberland counties. Rather than a spirit of competition for funding, Klein says that nearby counties and agencies work collaboratively to assist homeless folks, particularly since there is a high rate of migration between the regions.

The majority of Joseph’s House clients meet the HUD standards for chronic homelessness. According to Klein, approximately 50% of the individuals being served have a substance abuse disorder, 73% have a serious mental illness, and 80% have a disabling physical condition. Still, Joseph’s House is not content to achieve its mission “to work collaboratively with others to aid our homeless brothers and sisters by offering a continuum of services including emergency shelter and access to supportive housing and comprehensive social services” (via the agency’s website) by waiting for people in need to walk through its café doors. The agency is working, Klein said, toward hiring talented outreach specialists who will go out into the region to bring services to people most in need.

Many of the practices Klein described — such as street outreach, and an emphasis on nonjudgmental staff who co-collaborate with clients to develop meaningful plans of action — are borrowed from “low-threshold” drug treatment programs. But low-threshold programs, which emphasize harm reduction and individual autonomy, do not provide instant gratification for funders or digestible narratives for the public. Rather, they are designed with the primary aim of honoring a person’s dignity and humanity. “We are masters of accommodation,” the website reads. “We are flexible when we can be, working to meet individual needs.” Also: “Listening, without judgment, is key. We accept individuals where they are and how they interpret their experiences in the world. It is not our job to advise people about how to live their lives.”

Refraining from “advising” may seem an improbable stance, but Klein and his staff are committed to it. It also speaks to the special blend of top-down and bottom-up approaches evident in the agency’s governing philosophy. Klein emphasized credit due to other organizations that shared best practices and lessons learned during the infancy stages of Joseph’s House — he cited Project Home as a major source of guidance — but placed equal importance on the creation process undertaken by founding members. “You jump in, you get to know people, and their needs begin to emerge,” he said.

Having successfully established itself as a trusted presence in the community, Joseph’s House is looking to expand. Klein described plans to add additional space to the existing structure in order to build in on-site mental health services and increased case management. The organization is also looking into building and acquisition projects to increase affordable housing stock in the region.

Dedicated affordable housing is sorely needed. Despite some signs that Camden’s economy is picking up, the city continues to struggle with socio-economic and racial divides. Joseph’s House fills in some of those gaps, but it can only do so much. Klein said donations of time, in-kind goods, or money are all welcome. Also, he said, “Come pay us a visit. Nothing transforms your thinking and your heart like being here. It might be a little uncomfortable, but that’s a good thing.”