Jack the Ripper, the infamous 19th-century serial killer, was in the news last month when someone claimed to know his identity. What many don’t know is that Newark had its own “Jack the Ripper” scare a century ago. Jersey Digs reopens the case files of that murder spree.

The East Village was a poor and gritty slum in 1915. But the people there looked out for their neighbors, and families felt safe enough to send a young child on a quick errand.

That’s what happened to Leonore Cohn on the night she was murdered.

It was a little past seven o’clock at night when the five-year-old girl went out for a quart of milk. A cashier remembered seeing a suspicious “foreign-looking man” outside her shop that evening. Later, she clarified the stranger was Italian.

In the early 20th century, Italians were still a curiosity. These immigrants from southern Italy arrived with little and sometimes crashed at the flophouses on 23rd Street or visited the free clinic at Bellevue Hospital.

Locals read about their “dark-age” superstitions in newspapers: love potions, witches, and charms for the evil eye. It was all in good fun until a rumor started going around that they were performing human sacrifices.

“It is well known that among certain ignorant immigrants from the south of Europe,” read a story in the New York Tribune, “there is a superstitious belief that by sacrificing a little girl, they can be cured of certain complaints.”

With a pail of milk, Leonore arrived safe and sound at her tenement. The real danger was waiting for her inside. As she climbed the stairs to her apartment, Leonore was stabbed. The only clue was a lemon-drop candy, which wasn’t sold anywhere in the East Village.

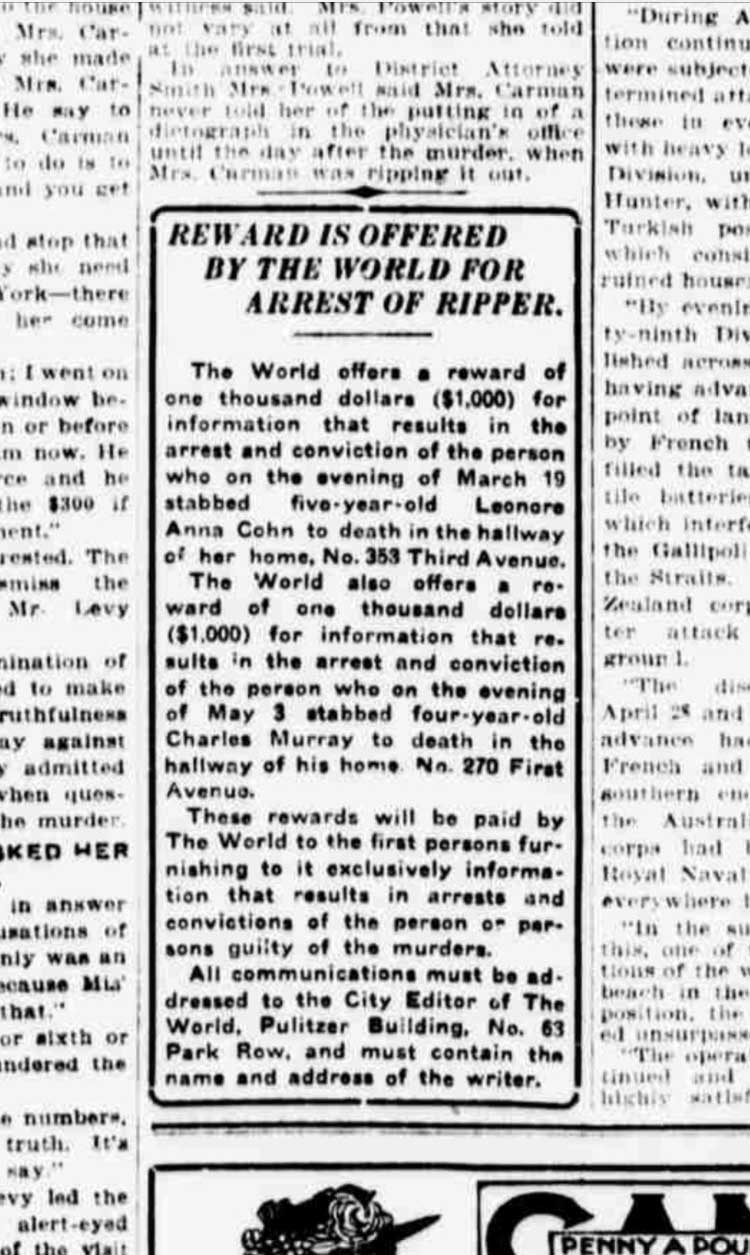

Four months later it happened again to a four-year-old boy named Charley Murray.

The newspapers nicknamed the killer Jack the Ripper after the London slayer. Publications began competing for the most egregious headline: “Police Suspect Man Who Often Masquerades in Women’s Clothing.”

Detective Joseph Faurot was assigned to the case. He was the foremost specialist in fingerprint analysis, a new forensic technique at the time.

Manhattan was put on complete lockdown. Federal agents swooped into town when the victims’ families began receiving letters in the mail from the killer.

“I sit in my room here in this neighborhood and watch the crowd of police looking for me,” read a letter sent to Charley’s mother, “but when this excitement cools off some evening after dinner I am going out to kill again.”

The initial suspects were mostly Italians, based on the description given by the cashier. Mary Murray, Charley’s eight-year-old sister, caught a glimpse of a similar stranger leaving her tenement on the night of the murder.

Many thought the killer might flee town. The entire metropolitan area was on high alert. In Newark, three suspects were detained on the same day. It was quite the spectacle when a crowd of 100 students from Lafayette Street School ran after a stranger loitering on school grounds. All three suspects were eventually cleared.

Perhaps the most promising lead was Edgar Jones. He worked near Bellevue Hospital at the time of the murder, then suddenly went south. In Baltimore, Jones (who was likely Italian as his girlfriend said his real surname was Fasco) was arrested for theft and drunkenness. Things took a wild turn when his girlfriend, also arrested, told police that Jones had confessed the ripper crimes to her. Her testimony fell apart, though, as police believed she was under the influence during her testimony. Once sober, she denied everything.

Detectives soon lost the killer’s scent and rumors went around that Faurot was going to be ousted. The New York Tribune ran a damning profile about him.

True-crime aficionados enjoy in-depth debates about Faurot’s investigation. The reason so many details exist about a century-old case is that newspapers had a habit of printing stories about suspects before they had been charged with a crime. Most of these suspects came from an underclass of dirt-poor immigrants and people with severe mental health issues who seemed to exist for the public’s entertainment.

For instance, suspect George Blumlein garnered a front-page story in the Evening Star. True, he confessed the murders to police, but at the time he was a patient at the “insane ward” at Philadelphia General Hospital. He also claimed there was an underworld plot to steal his organs. Detectives finally backed off when Charley’s mother, his former neighbor, came to his defense.

The East Village Ripper was never found and the Cohn and Murray families went to their graves without ever finding justice. The names of their slain children would sometimes appear in the news, connecting them to some gruesome crime. In time, however, they were forgotten.

As for Faurot, he remained on the force and is celebrated even today for introducing fingerprint analysis to the bureau. He retired in 1926 with a pension.