This is a guest post by R. Ballantine.

It was the jolt of the announcement that made the earth shake beneath my feet. Published on Jersey Digs a few months ago, it read like the most scandalous of headlines. The New Jersey Symphony Orchestra, a cultural institution whose Newark roots stretch back to the 1840s, was moving to Jersey City?

What indecency was this!? I almost spattered my beer onto the monitor at the sight of the headline. But after regaining my composure, and my urge to scream, I began to contemplate how something of this magnitude could have happened.

I turned my attention to that city that also bestrides the Hudson River, facing the direct line of fire of our most-pompous neighbor. I began to investigate the history of Jersey City, and what I saw was the most impressive of turnarounds.

Perhaps the ultimate tale of an urban underdog rising above the competition when no one was looking. Jersey City is having its moment in the sun… so how is it I’m only realizing this now?

‘One day, a great city shall rise on the western banks of the Hudson River.’ So said Alexander Hamilton when he spoke of the little towns that dotted this Garden State riverbank in the early 19th Century.

He was fastidious in this conviction, dedicating a considerable amount of his efforts to transforming New Jersey from a staid agrarian society into a model of industry and manufacturing long before the steam engine began to make waves across the world.

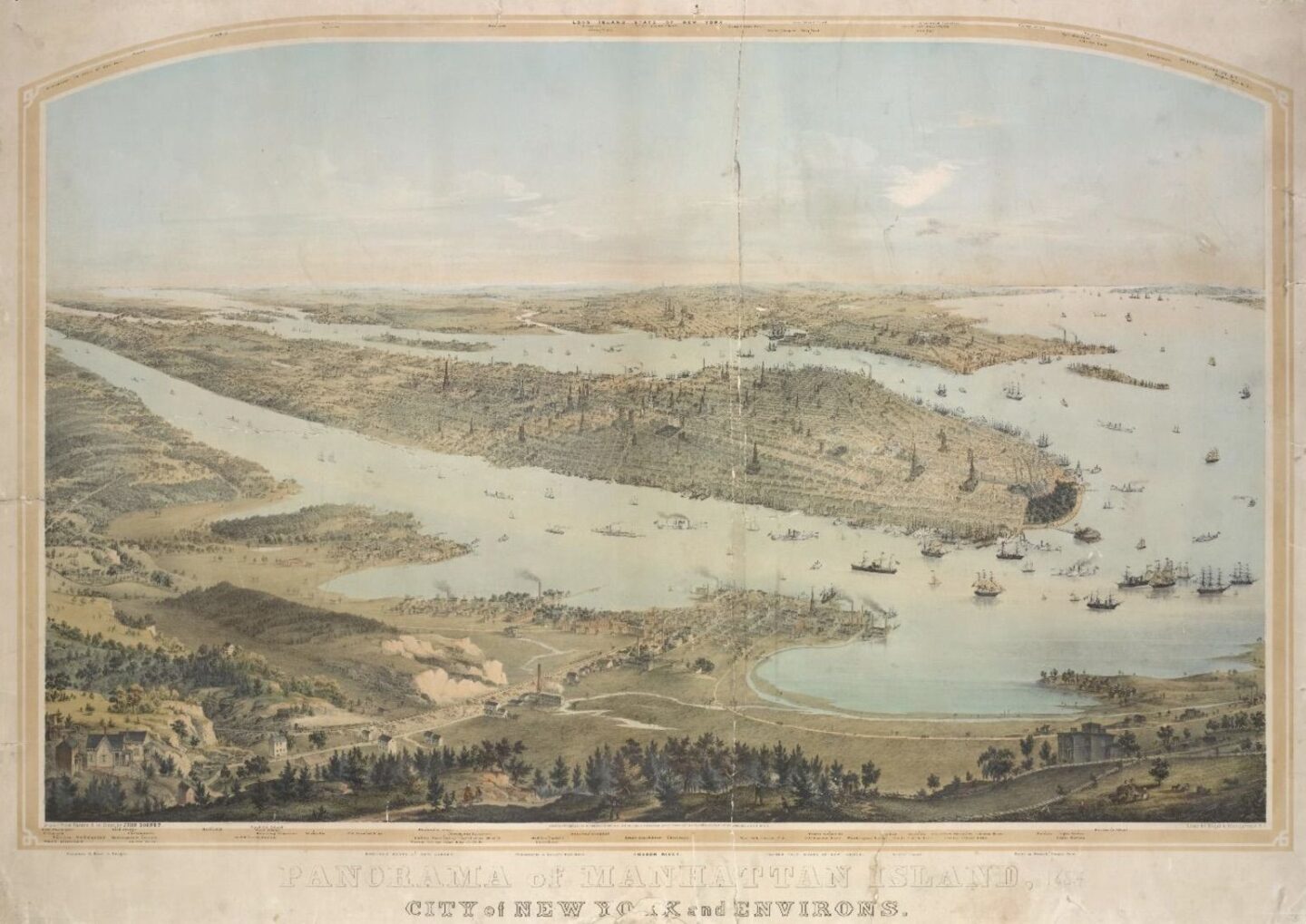

He most famously established Paterson as the prototype for an industrial center. Still, in his mind, he envisioned that this cluster of towns sandwiched between the Hudson River and Newark Bay would give birth to a metropolis whose might would rival that of NYC.

And from a geographic standpoint Hamilton appeared right, finished goods could flow downstream from the factory mills of Paterson down the Passaic River, where they could be transferred around and across the Bergen Neck (the peninsula Hudson County resides in), through the mouth of the Hudson River, out into the world beyond.

But Hamilton was naïve to think that the Empire State was ever going to let their civic crown jewel be usurped by some competitor at its doorstep.

The State of New York began to use the ambiguous and incorrect language of the original colonial charters of both states to claim that the mouth of Hudson River did not flow out to sea through the Narrows (of Verrazzano Narrows Bridge fame), but through the Arthur Kill at the bottom end of Staten Island.

The Empire State was not so much taking control of the Hudson River as it was taking the river hostage, going so far as to seize control of all docks on the New Jersey side of the Hudson for itself.

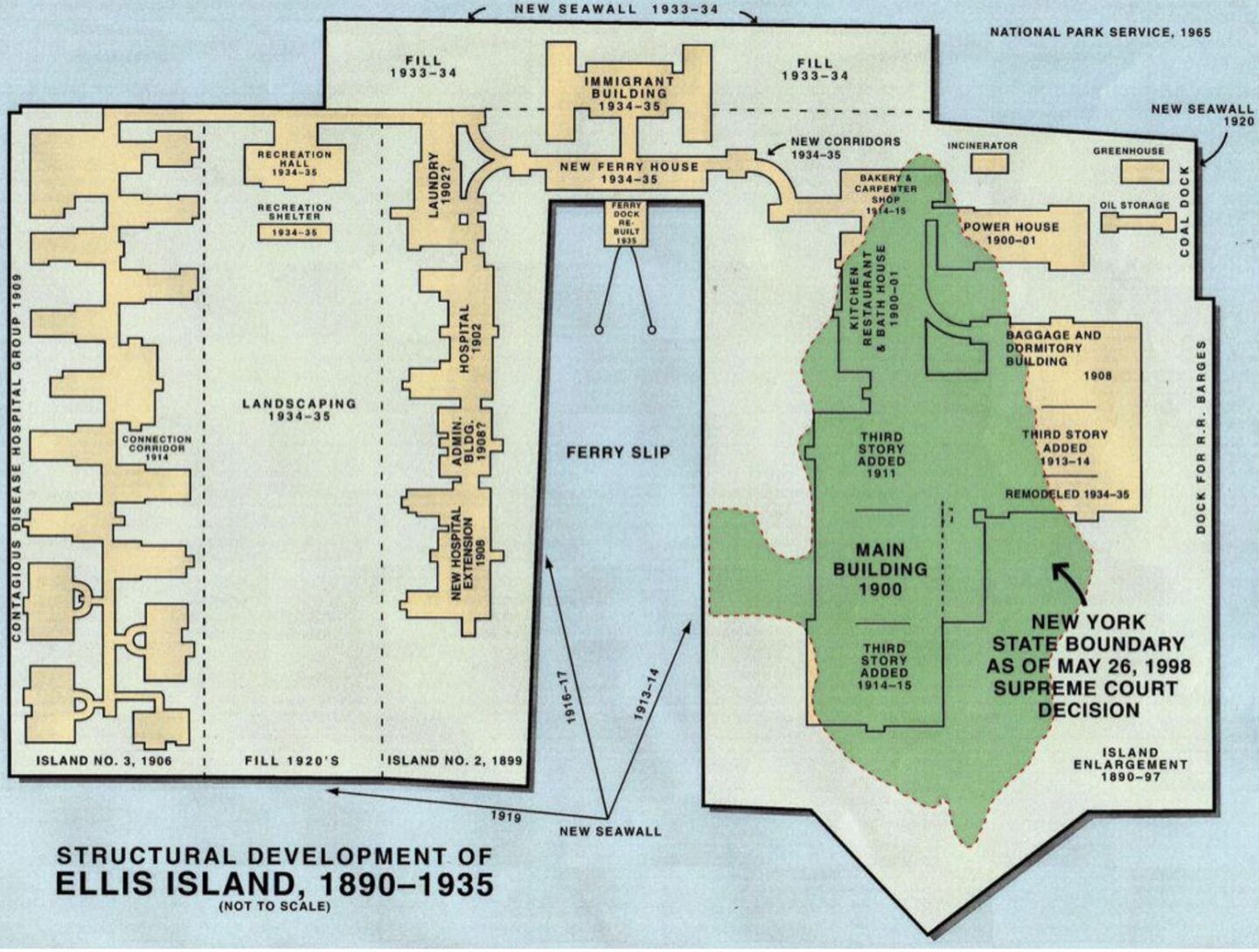

The dispute over river access and by extension ocean access dragged on for decades between New Jersey and New York. Only after several islands belonging to New Jersey (including Staten Island) were ceded to New York in 1834, our docks were returned along with access to the Atlantic Ocean via the Narrows. The towns that would later make up Jersey City languished because of this cross-state sabotage, developing slowly up until the second half of the 19th Century.

This inter-state squabbling indirectly helped Newark by extension, because industrial goods would still descend from Paterson into Newark docks and flow out to sea through the Arthur Kill. It is not that we lost all access to the Atlantic, we just lost easy access, and to add insult to injury the eastern banks of Newark Bay were too marshy and our technology too primitive to terraform the peninsula to make it possible for ships to dock.

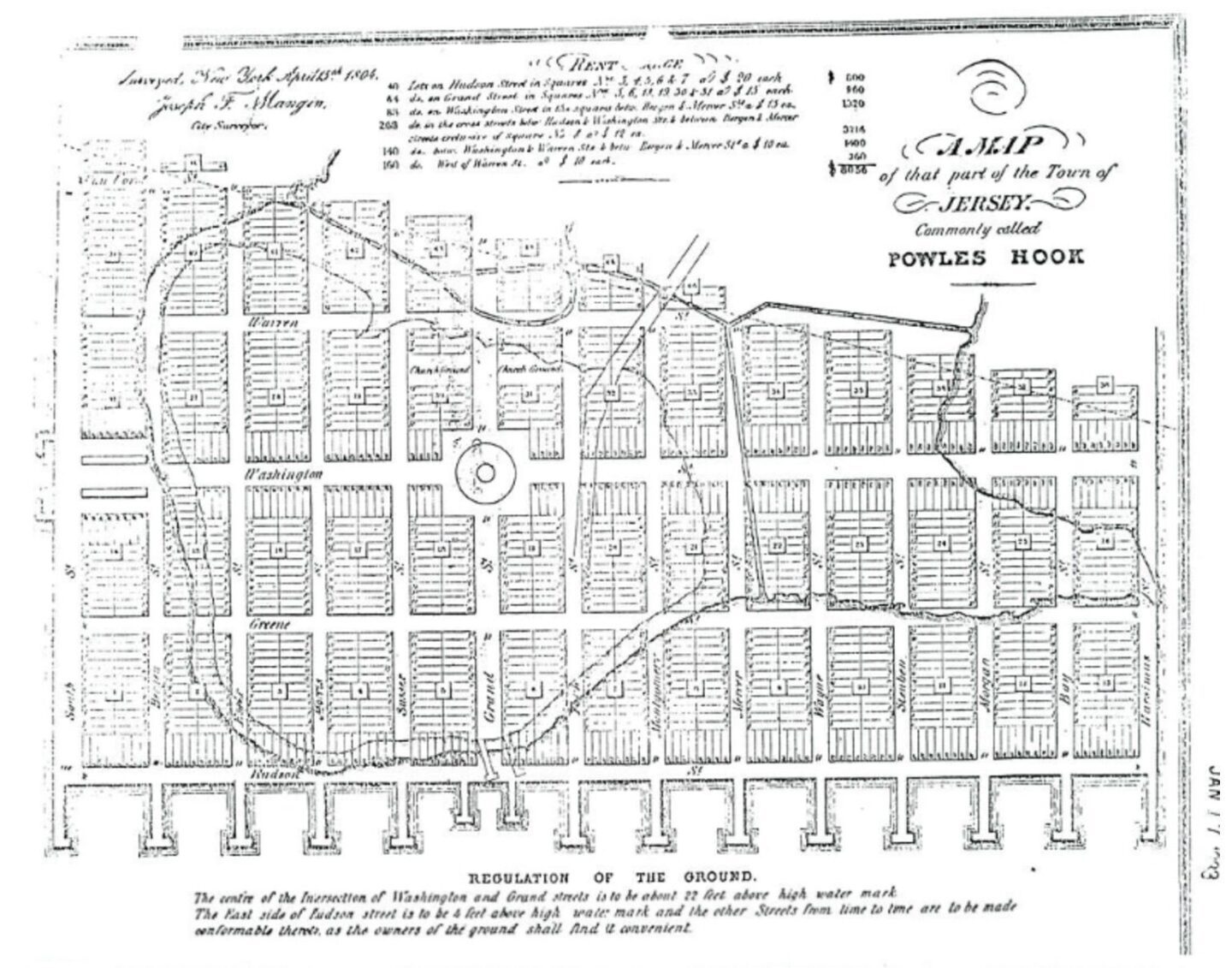

Although a city by the name of ‘Town of Jersey’ and later Jersey City existed by 1829, it was after the Civil War that the idea of consolidating these disparate villages began to coalesce. The towns of Hudson and Bergen merged with Jersey in 1869 and in 1870 the town of Greenville also merged with Jersey City creating its modern borders.

By contrast, Newark was trying to re-incorporate the various fragments that it sold off from its original colonial limits (i.e. ALL of Essex County) but was met by increasingly ravenous opposition from townships that did not want to merge with what they viewed as the large, polluted, industrial city and wanted to preserve their ‘natural’ environments and small town feel… where have I heard that before? But I digress.

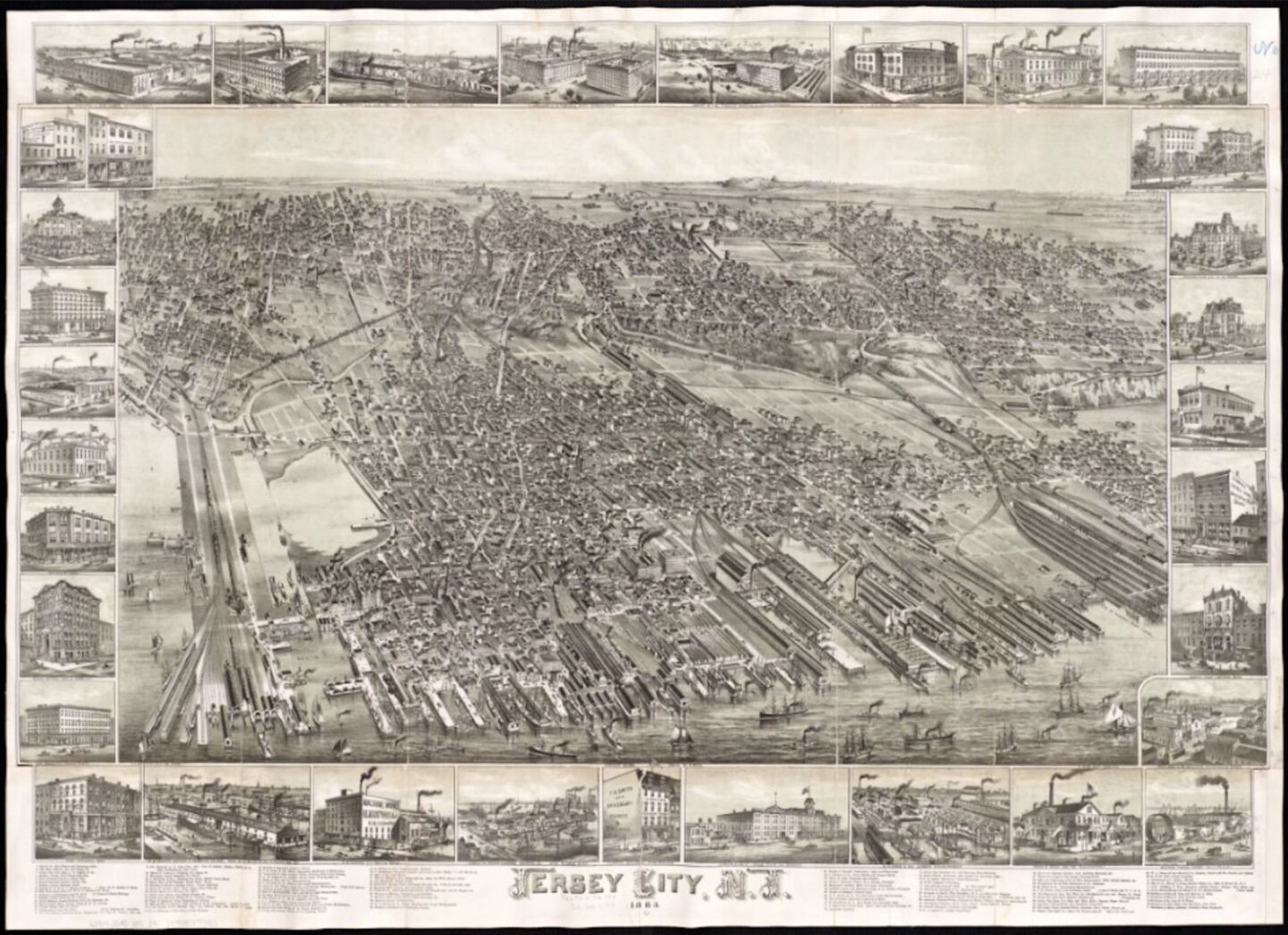

With access to the Hudson River restored, and benefiting from a greater pool of residents and municipal resources, Jersey City began to grow rapidly with the advent of the Industrial Revolution.

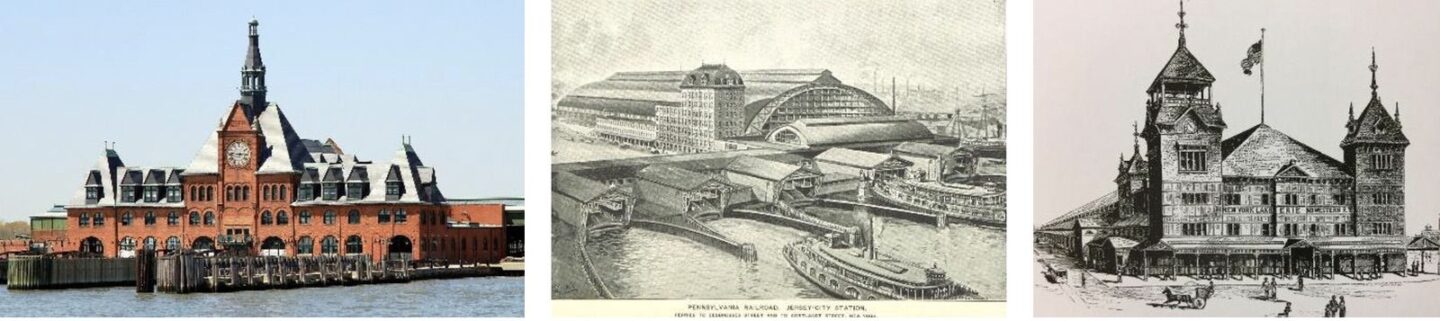

Jersey City became the final terminus for some of the largest railroads in the United States at a time when the idea of trains being able to cross the Hudson was seen as a mere pipe dream.

Dozens of piers lined along the riverfront carrying goods conveyed by rail from across the country into ships ready to send American goods around the world. Jersey City stood as the logistical middleman between two great cities (Newark and you know who…) battling it out to see who could best the other with Jersey City profiting from both. The city became an industrial center of its own, being the home of Colgate-Palmolive, Dixon Mills, American Can Company, and many other manufacturing juggernauts now lost to time.

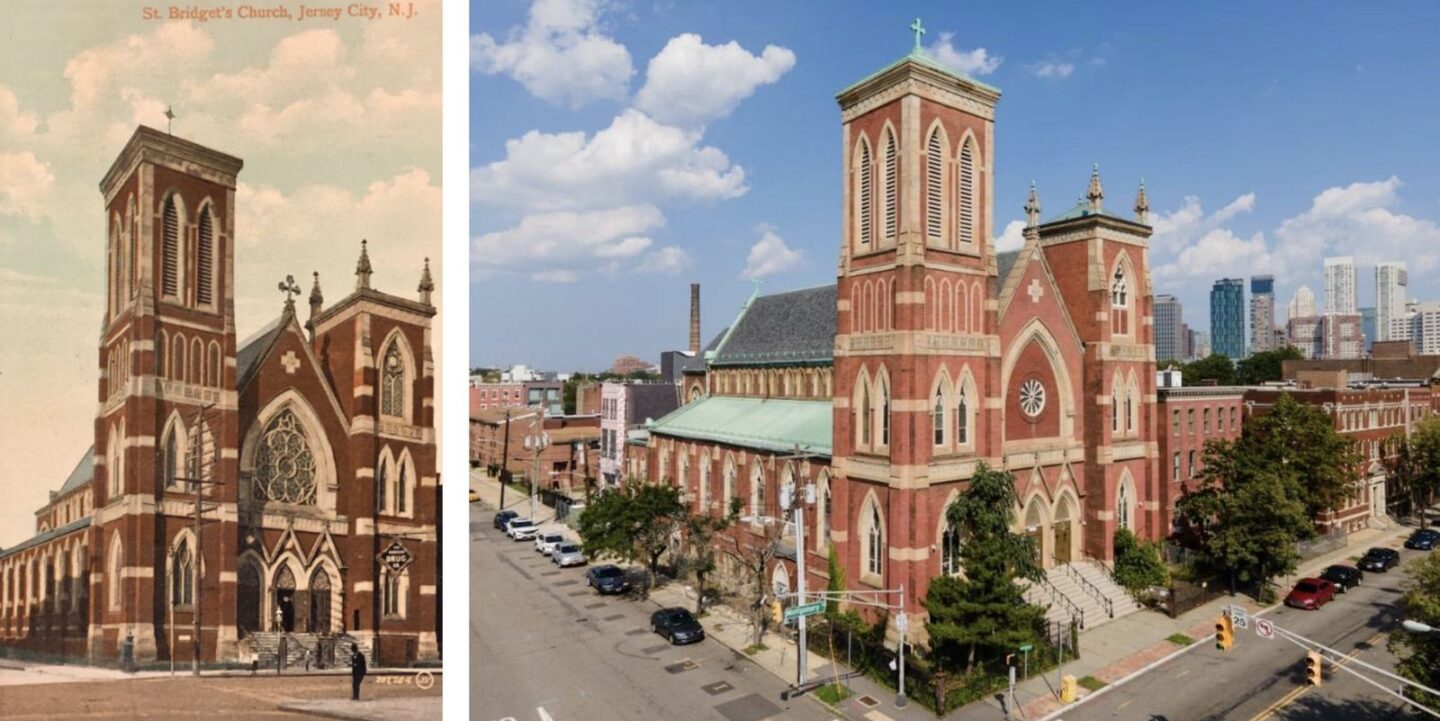

Urban pride began to swell with Jersey City’s economic achievements, The City Beautiful Movement began to leave its mark on the city with the construction of new cultural and civic institutions such as Lincoln Park and its glistening City Hall and Court House.

Fine and elegant mansions rose on the western side of the city as the upper classes left their brownstones in Paulus Hook and Hamilton Park, displaced by the swell of European immigrants choosing to live closer to their workplaces near the docks and railyards along the river. But cracks in the city’s prosperity began to form at the dawn of the 20th Century, and it started with a pipe dream that did come true.

The whirlwind of having tens of thousands of rail passengers interrupting their journeys at Jersey City terminals to board river-crossing ferries ended when the Hudson River Tunnels were constructed by the Pennsylvania Railroad in 1911. Jersey City’s importance was beginning to diminish as a direct connection between Newark and our cross Hudson Neighbor was prioritized.

The Hudson and Manhattan Railroad (now known as the PATH) would later build tunnels and connections to maintain commuter links between all three cities, but the priority remained to fuel the economies of the much larger cities and not the needs of some municipal middle child.

Jersey City would become a victim of destruction during this time. While the United States remained neutral during the first years of World War One, that did not stop German saboteurs from engaging in terrorism to frighten the American public into remaining out of the European conflict. On July 30, 1916, spies working for the German Empire set a series of small fires in a munition’s depot located in Black Tom’s Island just off the shores of the city.

This resulted in a massive explosion that shattered widows across the entire New York Harbor, killed several locals, and caused millions of dollars in damages. This event along with the torpedoing of the SS Lusitania (killing 136 Americans) the year prior is what helped drive the United States into entering the War in 1917.

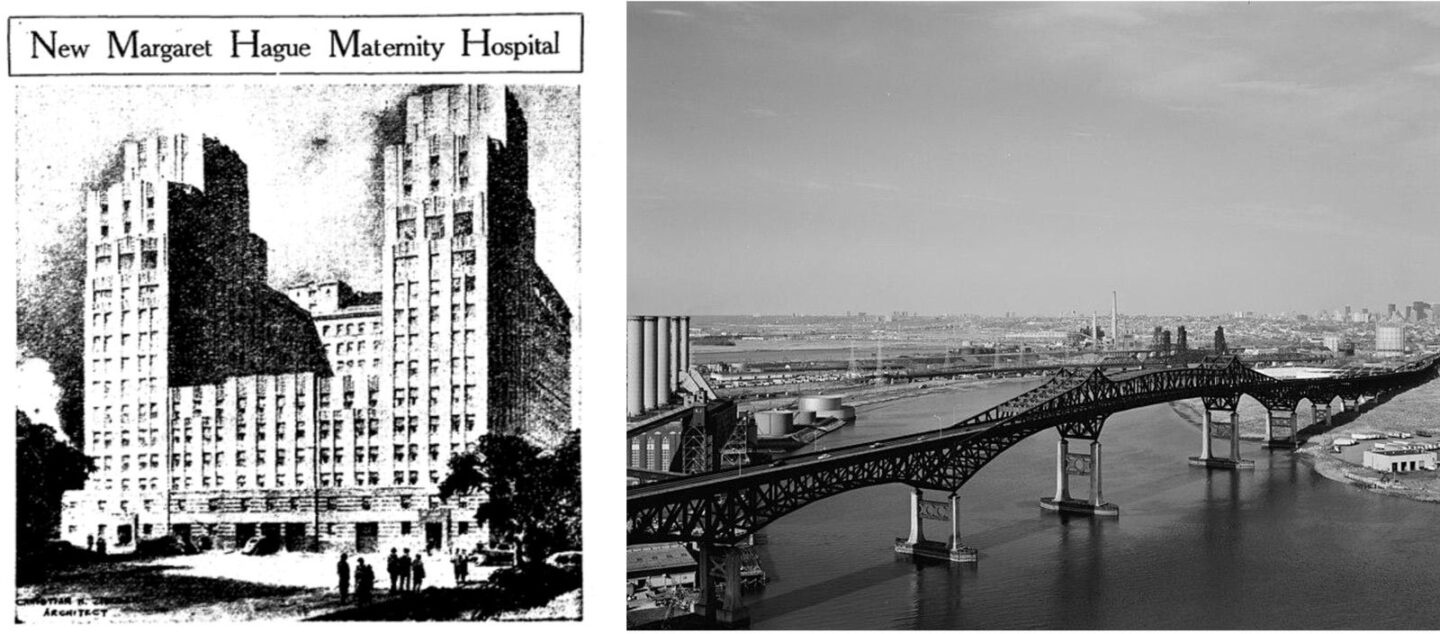

The city would also see the rise of its most famous, or most infamous elected public official; Mayor Frank ‘Boss’ Hague. Mayor Hague’s influence was second to none when it came to his city’s growth in the 1920s and its struggles in the ensuing Great Depression. He wielded immense power, to the point that it affected the highest level of government in both Trenton and Washington DC. His influence was significant enough to make waves in Newark’s municipal governance, but this man of the people was also entrenched in sweet scent of corruption.

Hague wore two masks; of a charismatic and magnanimous leader with a humble background, and of a ruthless political operator who dabbled in extortion and other criminal activities during his 32-year stint as mayor. He managed Jersey City, if not ruled it, like a benevolent despot from his suite at the Plaza Hotel across the Hudson River. Other writers have done better justice to write of Frank Hague’s legacy, which controversial or not, still casts a long shadow on his successors to this day.

The Port of Jersey City had remained the engine of growth for the city after World War Two and into the 1950s, but like Newark and other industrial cities, Jersey City was facing the same headwinds of demographic shift and middle-class flight.

Passenger traffic from its riverfront terminals had steeply worsened, but heavy freight was still crucial to economic output. Industry was outsourcing labor and production facilities into the suburbs, but proximity to the docks still weighed heavily to the bottom line of companies wishing to export.

Jersey City’s fate lay upon the success of its docks and its riverfront warehouses, without them, the city would return to the same economic stagnation it endured in the early 19th Century. However, as if coming out of nowhere, a fatal blow was dealt to Jersey City’s prosperity.

Another act of economic sabotage by an opponent was committed. It came from across the river, but not the Hudson River as expected but from across the Passaic… it was Newark. The Brick City inadvertently killed its neighbors’ fortunes in a desperate attempt to save its own.

Malcom Purcell Maclean was a businessman with a plan. For centuries, freight had to be manually loaded from factories and workshops to ships and freight trains only to be transferred into warehouses for distribution to local markets or be re-shipped by other conveyances long distance.

When it came to perishables such as produce and frozen foods, this process had to be done quickly and required a lot of manpower, making shipping across the country and the world an expensive and time-consuming endeavor. Mr. Maclean saw this inefficiency and made a bet on the future, he invented what is now known as the intermodal shipping container.

On April 26, 1956, the ocean-going cargo ship ‘S.S. Ideal X’ was modified to transport Maclean’s standardized containers. The ship left the Port of Newark bound for Houston, Texas, and in one fell swoop the price of shipping goods around the world collapsed, making way for the interconnected globalized economy we now enjoy. Mr. Maclean changed the fate of history, and Newark successfully secured its place as one of the great cargo ports of the nation.

This pioneering step towards tomorrow, however, rendered the docklands and Victorian warehouses of Jersey City obsolete. Some argued it was the dock-worker’s resistance to change that made Port Newark the better candidate for containerization.

While others believed that Newark’s economic fate was more important to protect than that of some ‘podunk’ town in Hudson County; it all proved to be a moot point, after 1956, it was game over for the waterfront’s prospects. Jersey City would begin to rapidly decline from the 1960s into the 1970s. The booming docklands were reduced to rotting piers stretching out onto a polluted river, and hundreds of miles of railyards were left to rust in a toxic wasteland.

Jersey City’s economic fate and civic standing had reached rock-bottom. The city did not implode the same way Newark did during the Riots of 1967, but Jersey City in the 1980s had stoically accepted that it would never live up to the dreams and aspirations of Alexander Hamilton… that was until a real-estate tycoon from across the Hudson set foot on that forgotten waterfront, looked around and out onto the island of Manhattan and said; ‘Wow, what a view! A great city shall rise on the western bank of the Hudson River… and I will be the one to build it.’

Join us for Part II as we narrate the rebirth of Jersey City and its (supposed) rivalry with the Brick City. A battle to the death for the title of largest City in New Jersey, and whether it will be all worth it in the end.