Two decades ago, there was a sudden rediscovery of “Doo Wop” motels in the Wildwoods. These futuristic- and island-themed accommodations were frozen in time from an era when singers like Chubby Checkers, Frankie Valli, and the Supremes crooned at local clubs.

But at the same time tourists were falling in love again with these kitschy designs, came a real estate boom that endangered them with demolition. A wave of teardowns erased about 200 of these motels, and preservationists had all but given up on establishing a historic district dedicated to this quirky decade in architecture. Now, a new generation of historians is determined to save what remains.

“We are trying to pick up the pieces and figure out a preservation strategy that works,” said Taylor Henry, chairperson of Preserving the Wildwoods.

Her plan is to establish a historic district, but this time, broaden the range of architectural styles to include older Victorian homes and Craftsman-style bungalows that can also be seen on the five-mile-long barrier island. This wouldn’t be the first attempt of its kind. In 1993, the late architect John Olivieri carried out a survey of the City of Wildwood. His report, in fact, led to the formation of three eclectic historic districts that were, for some odd reason, ignored during most — if not all — of their existence. Most puzzling, these districts existed during the condo craze of the early 2000s and could have saved a number of landmarks had local legislation been enforced.

“Before the building boom, a Wildwood Historic Preservation Commission (HPC) formed in 1997 in response to Olivieri’s study,” Taylor wrote in her book “Wildwood Houses Through Time.” “The HPC did not last, likely because of a lack of means to enforce preservation, combined with hostility from property owners toward municipal influence over the aesthetics of their properties.”

Henry said that while researching for her book, she confronted officials at City Hall about these ghost districts and why they weren’t enforced. “It really is puzzling,” Henry told Jersey Digs. “I have asked people who were around then or who were involved, but not many people seem to want to talk about it.”

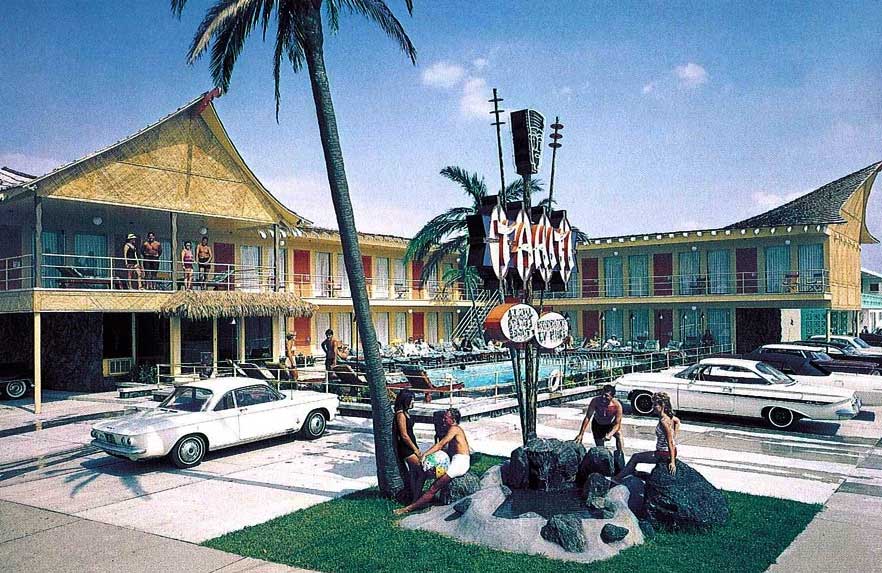

The Wildwoods, as we know them today, began after World War II, when more working-class families had cars and disposable income. The Garden State Parkway had just opened and the Doo Wop music craze was in full swing. This was the dawn of the motel — usually an L-shaped, two-story hotel that wrapped around a pool.

“Much of what made these hotels so visually stimulating were the embellishments — the superfluous decoration that gave each individual motel a sense of place on an island filled with hundreds of other motels identical in body and plan,” said Stephanie Hoagland, an architectural historian, at a recent panel hosted by Preservation New Jersey.

Hoagland, who worked for the Doo Wop Preservation League during its attempt to establish a Doo Wop Historic District, completed an architectural survey of hundreds of motels. It was a race against the clock, though. In a matter of only two years, her proposed historic district had shrunk from 43 blocks to 23 blocks due to a wave of demolitions.

“While it seemed that many hotel owners were excited about the idea of Doo Wop, when the developers showed up offering twice what their property was worth, they were still ready to sell,” Hoagland said. “Unfortunately, by this time the historic preservation office felt that the integrity of the area had fallen below the point of creating a cohesive historic district.”

The failed attempt to establish a Doo Wop district has become a cautionary tale in the preservation world. One of the takeaways is the need to offer better incentives to property owners to compete with the offers from developers. Fortunately, Downtown Wildwood was chosen this year for the statewide Neighborhood Preservation Program, which will supply the municipality with $125,000 in grant money.

In the meantime, most of the Doo Wop motels have been listed separately on the state register. A number of mid-century landmarks, like the Lollipop Motel, have also been saved by sensitive conversions into condominiums, but these scenarios rely on the good graces of owners who understand the value of preservation. Establishing local historic districts is the best means of protection, Henry said, as long as the city enforces them this time.

”I know Stephanie has said that the integrity of the district has been destroyed — and she’s probably right,” said Henry, who was honored this year with the Young Preservationist Award by Preservation New Jersey. “But I also wonder, maybe there is still a way.”