In 1933, Newark’s population was at its historical peak and the school district was bursting at the seams. The opening of Weequahic High School in September of that year was intended to relieve the terrible overcrowding. But the $1 million Art Deco schoolhouse designed by Guilbert & Betelle would come to signify much more than that. Last November, its importance to the entire state was recognized when it was named to New Jersey’s Register of Historic Places through the efforts of Newark Landmarks.

The school’s inclusion on the state register, which now makes it eligible for listing on the National Register, helps further cement the legacy of its designer Guilbert & Betelle, a Newark-based firm that was well known in its day but whose memory has faded over the years.

“Guilbert & Betelle are major architects and kind of forgotten in a way,” said John Gomez, founder of Jersey City Landmarks Conservancy and member of the state review board that approved the listing.

“They get confused sometimes with Cass Gilbert,” said Michael Mills, principal at Mills + Schnoering Architects, also a state review board member.

Confounding the issue more, James Betelle, cofounder of his namesake firm, did work for the famed Gilded Age architect Cass Gilbert at the turn of the last century. In 1910, however, he and Ernest Guilbert, who was not related to Cass Gilbert (note the different spelling of the surname), eventually broke out on their own, a gutsy move as they didn’t have proper funding. To support their daily operations the partners went without a wage for a time, and to save on overhead, they opened a humble office in the attic of an art shop in Newark.

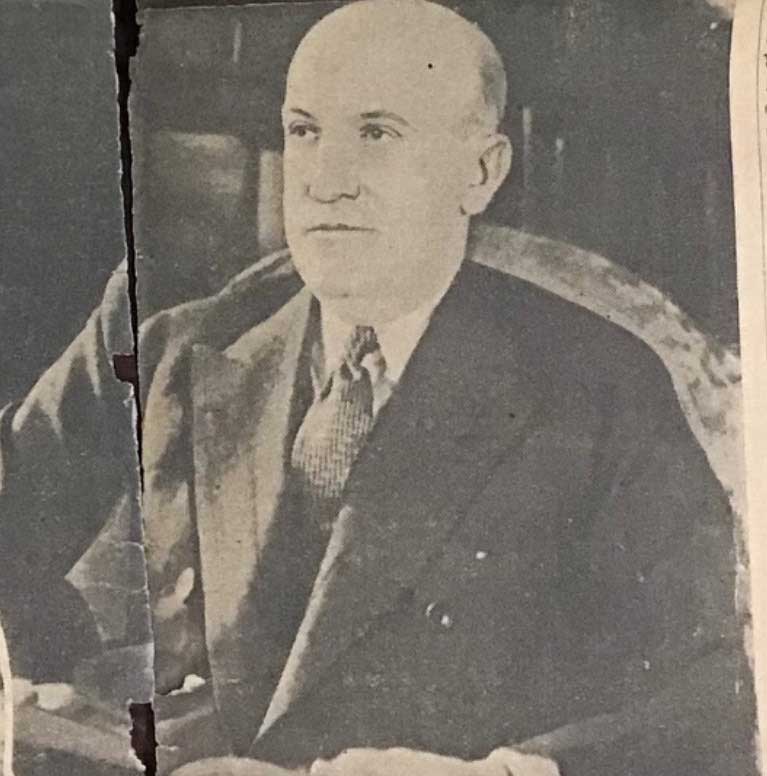

Despite two major setbacks — the outbreak of the Great War and the death of his partner Guilbert in 1916 — Betelle persevered. By the 1930s, when Weequahic opened, his firm occupied an entire floor of a building he designed, Newark’s Chamber of Commerce Building, which still stands today at 22 Branford Place. On the 20th anniversary of his firm’s opening, a Newark News reporter called him “one of the greatest authorities on school building design,” having designed more than $70 million worth of schools.

While other architects dabbled in school architecture, for Betelle, it was a lifelong passion, authoring essays on the topic. One thing Betelle tried to convey in his writings was that schools should not only be functional, but beautiful as well. “Good tastes dictate that we should conform in dress and deportment with the habits of the community, and this applies to our buildings as well as our general behavior,” Betelle wrote in an essay called “Architectural Styles as Applied to School Buildings.”

Beautiful schools cost more to build, but Betelle argued the money was well spent because they improved society, created productive citizens, and could double as community centers.

“It has been well said that the larger the school, the smaller the prison,” Betelle told the Newark News.

Betelle was fortunate to live in an era marked by the large-scale building of schools. The reason for this surge was to make up for the halting of domestic construction during World War I, which was immediately followed by a booming post-war economy.

Throughout his career, Betelle favored the Collegiate Gothic style because it was “scholastic in nature.” It was also more functional as it allowed the architect more freedom in the placement of large windows that allowed natural light to flood classrooms. Other styles, such as the Colonial or Classic style, came with prescriptions on where windows should be placed that resulted in dimmer interiors. The many schools he designed in the Collegiate Gothic style include Columbia High School in South Orange, South Side High School in Newark, and the Central King Building on NJIT’s campus.

However, in the 1930s, Betelle became enamored with Art Deco, constructing Arts High School, Weequahic High School, and the Essex County Vocational School on North 13th Street, all in Newark, before closing his firm for good in 1939. Today, with Betelle’s contributions, Newark has more Art Deco schoolhouses than any other place in New Jersey, according to Rachel Craft, a historian at Hunter Research, the firm that authored the state register nomination.

The reasons why Betelle walked away at his prime are the subject of much conjecture. He was only 60 years old at the time. But his writings suggest he believed he had left a sufficient mark on his trade. American art and architecture, for much of the nation’s history, had suffered from an inferiority complex. Inspiration for the design of new buildings was taken from the Italian Renaissance, Greek antiquity, the French and English medieval era, even Egypt. Whatever the case, the source material always came from a faraway time and place. But Betelle believed the 1930s marked a shift when modern American architecture had come into its own.

“European school buildings have very little to offer us so far as new designs are concerned,” Betelle wrote in a 1932 essay called “Trend in School Building Design.” “Very few schools have been erected in Europe since the war, so that America has the best school buildings in the world. Europe must come to us for new ideas in schools as she has had to do in other lines.”