The airline industry took a major nosedive last year when the coronavirus pandemic began. Experts warn that now is not the time to scale back on funding, but to go all-in on stimulus dollars for Newark Liberty International Airport.

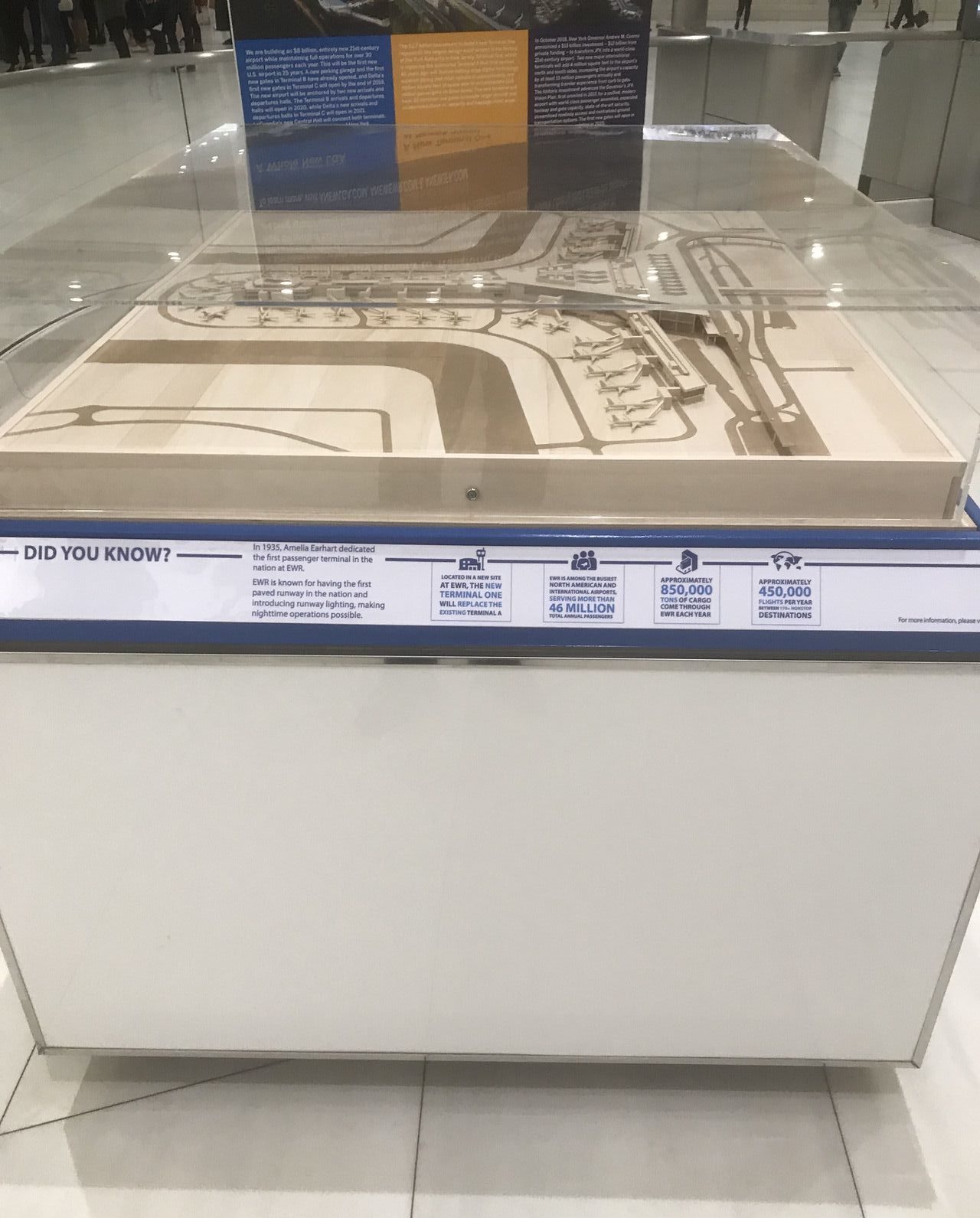

Major investments — nearly $3 billion — have already gone into building a new terminal at Newark Liberty. The 33-gate Terminal One, which opens later this year, is expected to ease congestion and usher the region’s busiest airport into the modern age.

The Grimshaw-designed terminal also gives the city a chance to move past an antiquated model of airports as a place where travelers merely arrive and depart, according to industry experts at a recent NJIT panel.

The idea for a so-called airport city — sometimes called an aerotropolis — is a 20th-century urban model that sees airports as a destination in their own right. A number of cities across the globe have seen a major boon to the economy by creating a secondary business center based around an international airport. Many of these airport cities, notably the one in Amsterdam, were born out of economic recessions similar to the one the world is experiencing today.

The concept for Netherlands’ airport city began in the 1980s when the nation was facing massive unemployment. The Dutch government decided to gamble on Amsterdam’s airport someday becoming an economic driver.

“That’s when they recognized the airport might help in an internationalized world in getting the economy going and increasing employment,” said Maurits Schaafsma, an urban planner at the Schiphol Group, who participated in the panel.

The initial investment paid off. In the 1990s, the neighborhood around Amsterdam Schiphol Airport began developing into 15 acres of prime real estate, where rent levels are now competitive with Amsterdam’s central business district, Schaafsma said.

Industry experts are hopeful that the U.S. government will make a similar timely investment in Newark’s airport. There is a chance that President Joe Biden’s American Jobs Plan — which proposes a $600 billion investment in infrastructure, including $80 billion in Amtrak alone — could find its way to Newark and serve as a down payment on an airport city.

A diverse South Ward — with hotels, restaurants, commercial ventures, and rail connections, all centered around the airport — would make the neighborhood less beholden to air travel alone, stabilizing Newark’s economy in the case of another pandemic or economic downturn.

“Compared to our competitors in Europe, we’ve been hit less hard,” said Kjell Kloosterziel, director at the Royal Schiphol Group. “One of the main reasons for that is that we have developed an extensive portfolio of real estate, which we call the airport city.”

The success of Newark’s airport city, however, hinges on it becoming a state-of-the-art transportation hub that would rival Newark Penn Station. A new head house could connect airlines to local and regional rail lines, such as Amtrak, NJ Transit, AirTrain, as well as the PATH train. High-speed rail connections, such as Amtrak’s Acela, would also be crucial in relieving air travel congestion.

This year, the Amsterdam Metro is building another extension to connect the airport to Hoofddorp and Haarlemmermeer. The Schiphol Station is now a busier train station than the one in The Hague and has helped lure corporations and government agencies away from bigger cities. Last year, the European Medicines Agency moved from London to Amsterdam.

Urban planners believe that Newark has to be similarly forward-thinking with transportation investment. The idea for a PATH train extension has been kicked around for the past few years. A new stop on this four-city commuter line would be a shot in the arm for Newark’s South Ward in the same way the Orange Line extension was to Chicago and the way the AirTrain was to Jamaica, Queens.

“When that was extended all the way to the Chicago Midway airport that began such a big community revitalization and economic development tool,” said panelist Vonu Thakuriah, dean of Rutgers’ Bloustein School of Planning and Public Policy.

According to Thakuriah, the extension not only gave travelers better access to downtown Chicago but also gave the outer neighborhoods better connections to the Chicago Loop, the nation’s densest job market.

Fortunately, the infrastructure for a PATH extension already exists. But the Port Authority, which estimates a $1 billion price tag, still believes a new stop at the airport is “still a ways away” due to funding and land acquisition issues, according to Peter Simon, chief of staff to the Port Authority chairman.

In the meantime, Schaafsma believes it’s important to create an “attractive environment” at the airport where people want to spend time.

“The situation in Newark is quite comparable to the Schiphol situation, because we are also close to a very attractive city and people really want to be there,” Schaafsma said. “But on the other hand, not everybody wants to spend time. Sometimes you want to be efficient. You want to just fly in or come in by train, and come out. For that market, you want to make an attractive environment.”

With smart planning, Newark’s South Ward could open up to the 4.3 million people that landed at the airport in 2019, according to Chris Watson, the city’s planner, who attended the panel. “If a million people had a 12-hour layover, where did they spend that time? Let them spend it in Dayton,” Watson said. “I could play 12 rounds of golf at Weequahic Park.”