As the former state capital, and a major manufacturing center in the last century, Elizabeth, New Jersey, might be one of the most important cities in the nation without a commission to protect its historic landmarks.

“Anything could come down at any moment if a developer has an eye for it,” said Paula Borenstein, founder and vice president of the Elizabeth Arts Council.

A walk down Broad Street reveals graveyards of Revolutionary War soldiers, Gothic spires, and Art Deco masterpieces. The city is a special place, but painfully unaware of its own potential. With all the popularity of the musical “Hamilton,” shouldn’t the city where the founding father lived at least have a gift shop?

“There’s a lack of vision,” Borenstein said.

A decade ago, the Arts Council founded a committee to protect the city’s landmarks. The members, however, don’t have any official oversight to prevent demolition.

“Our power is in our activism,” said Borenstein, who wrote the nomination that eventually landed Elizabeth on the Preservation New Jersey’s infamous list of most-endangered places in the state.

But even the most tireless activism is hand-tied without the law on its side. For instance, Borenstein also wrote the nomination for the Whyman Parish House, which made the endangered list in 2016. But the 19th-century Italianate home was demolished last year despite its designation on the National Register of Historic Places, Jersey Digs reported.

Different schools of thought have their own ways of trying to persuade communities that preservation is worthwhile. “Don’t argue aesthetics,” an architectural historian from Newark once said. “It’s better to make an economic argument.”

“The advice I once got was,” Borenstein said, “‘Don’t say that historic preservation will bring tourists. Instead, do it for the locals.’”

Nowadays, Elizabeth is a city of immigrants — about half of its residents are foreign-born. A question historic preservation often wrestles with is, how do you engage a community with a history that isn’t theirs?

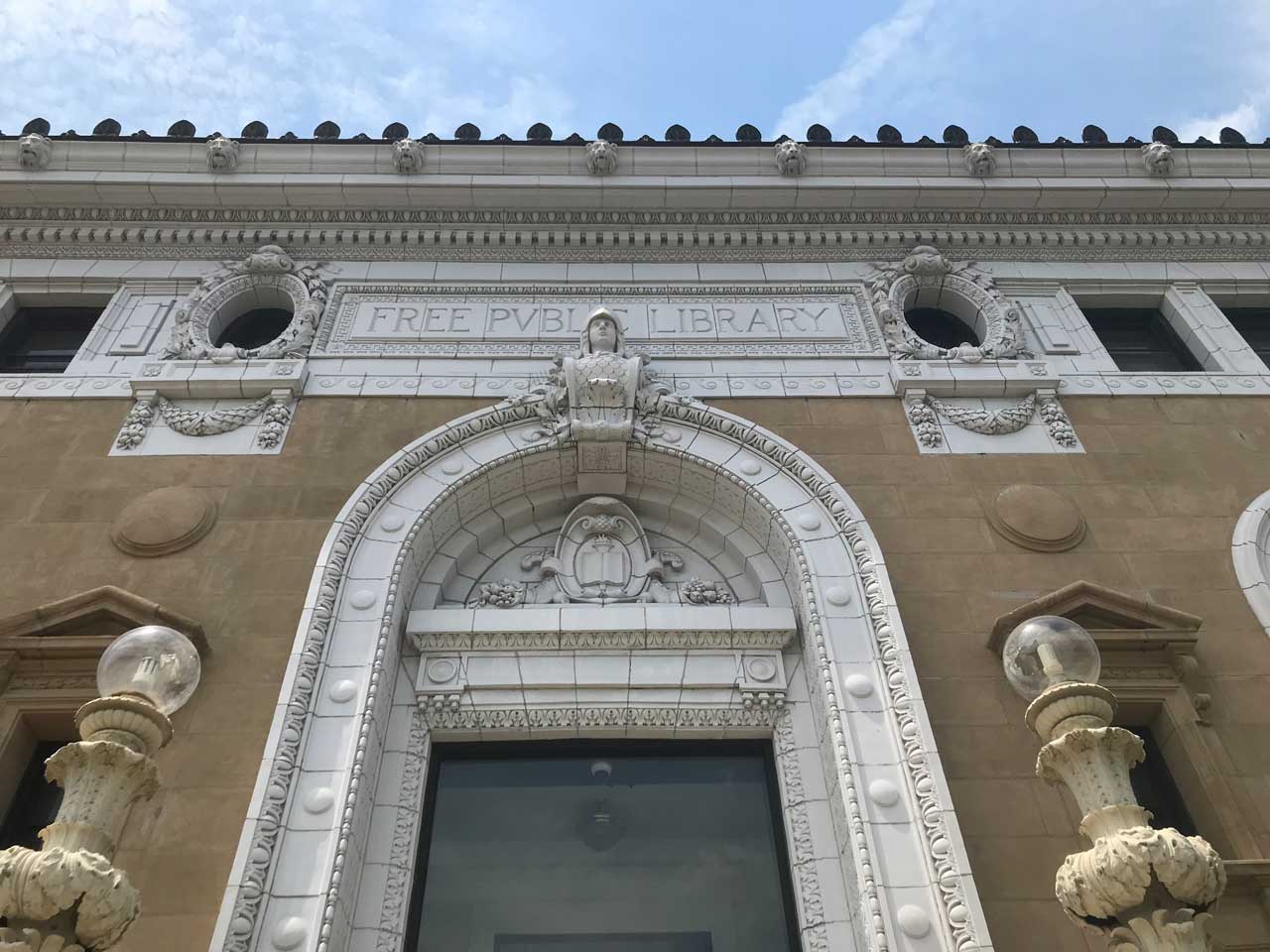

“Right where we’re standing, George Washington came here during the Revolutionary War,” said Elizabeth-based artist Daphnie Manzione, standing at the Elizabeth Public Library, where she has an art exhibition that explores issues of social justice and history, such as the demolition last year of the Third Presbyterian Church. “But people don’t get excited because they have their own history. There hasn’t been room for their history to be told.”

The public library, formerly the site of a Colonial-era tavern called the Red Lion Inn, also happens to be the first stop on the city’s official downtown walking tour, published in 2010.

“You’re going to see that a lot of places aren’t there anymore,” Manzione lamented.

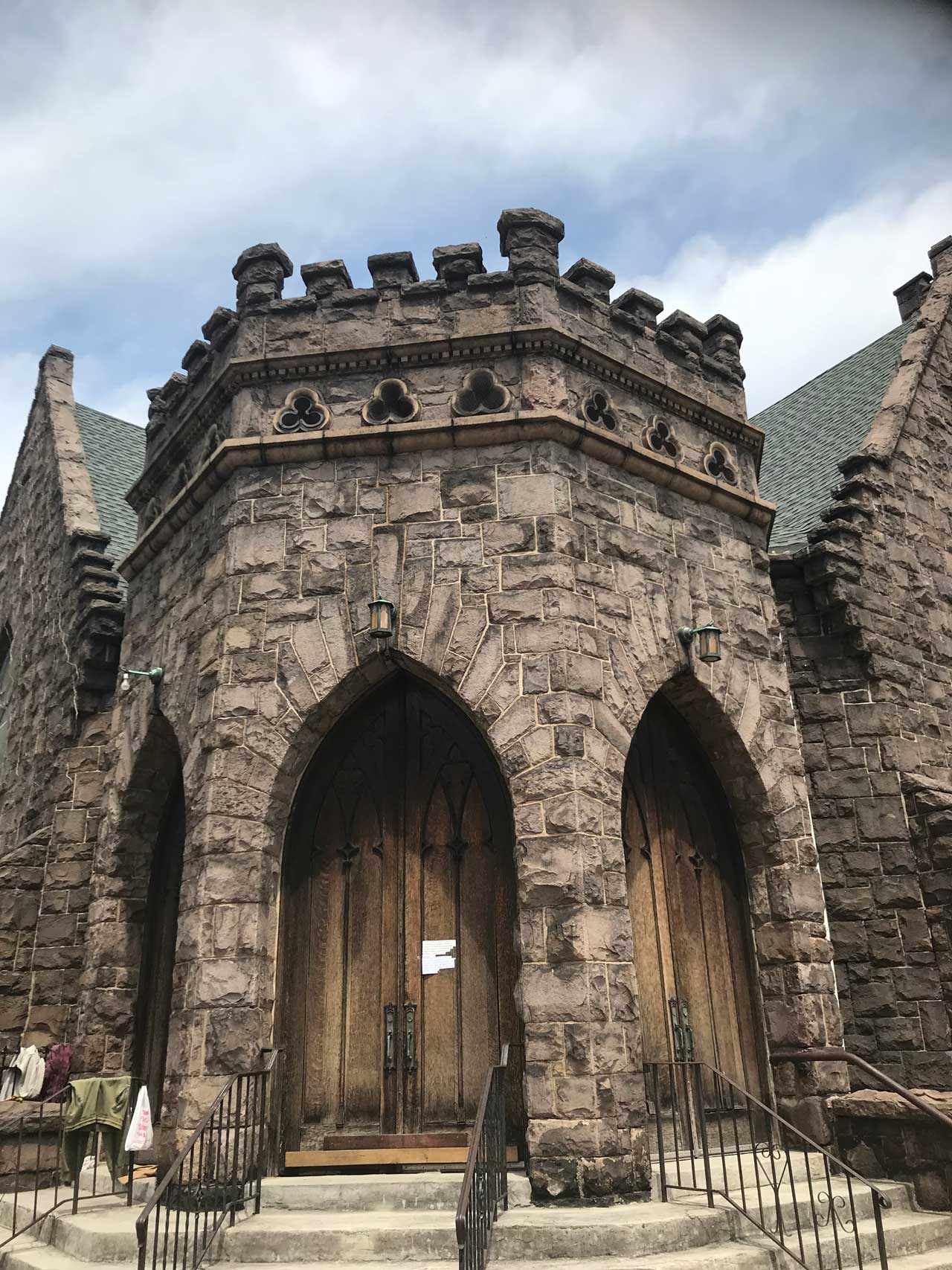

It is an unofficial measure of the city’s vanishing history that several of the sites on the tour have been demolished in the past few years alone, most notably the Third Presbyterian Church, built in 1855.

“That was the straw that broke the camel’s back,” said Borenstein, who decided to do something unprecedented in the history of the most-endangered list. “I said, ‘You know what? Let’s nominate the whole city.’”

Borenstein acknowledges that the state of the church at the time of demolition left little hope for restoration. But the real issue, in her eyes, is how could long-standing elected officials, namely four-term Mayor Christian Bollwage, allow a historic building beside City Hall to deteriorate to a point of no return?

“How could you go to work every day and not notice that a 19th-century church is falling apart?” Borenstein said. “The mayor is dead-set against a commission. He said it impedes development.”

Attempts to reach Mayor Bollwage and Sixth Ward Councilman Paul Mazza were unsuccessful.

Neglect, though, is not always caused by indifference, according to Katherine Craig, the curator at Boxwood Hall, a local museum on the National Register. Elizabeth, much like nearby Newark, used to have a well-known shopping district that featured department stores like R.J. Goerke Co. and Levy Brothers. Broad Street began to lose its cachet in the mid-century era during the rise of the suburban shopping malls, Craig said.

“I remember being in Newark as a kid during Christmas. It was so crowded we thought we were in Manhattan,” said Craig, who authored the downtown walking tour.

In order to sell the community on the importance of preserving its history, preservationists must demonstrate how local businesses will reap the benefits of landmark designations, Craig said.

“People hear the word historic preservation and they think people are going to tell them what color to paint their house,” Craig said. “Maybe we need another term.”