A century ago, a small suburban hospital in Orange, New Jersey, became a sprawling, world-class medical facility funded by the era’s most famous philanthropists. But this landmark institution had a tragic, mysterious ending. In this series, Jersey Digs explores those who worked, healed, and died there.

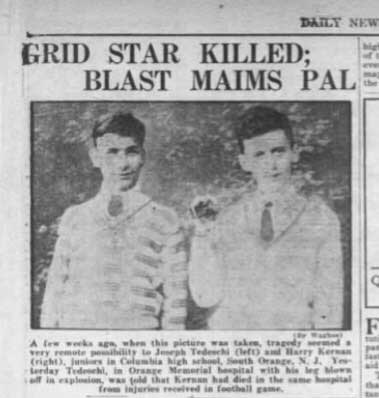

It was no small feat that Harry Kernan made the football team for the first time in his junior year. Coaches don’t usually give upperclassmen a chance like that. Now, it was up to the 17-year-old Columbia High School student to prove himself.

In a game against Irvington High School, Kernan made a spectacular thirty-yard carry. But he needed to show it wasn’t a fluke. He tried to recapture the glory in the second quarter. Instead, he was thrown back by a hard hit. The pile cleared. The teen was unresponsive. He was rushed to Orange Memorial Hospital, where he died two days later of a broken neck.

Kernan’s death happened a century ago, when football was truly a live-or-die gladiator sport. In fact, his death wasn’t even the first in the Oranges. In 1909, one of the sport’s deadliest years, a West Orange High School student named Albert Wibiralske died in a game at Watsessing Park.

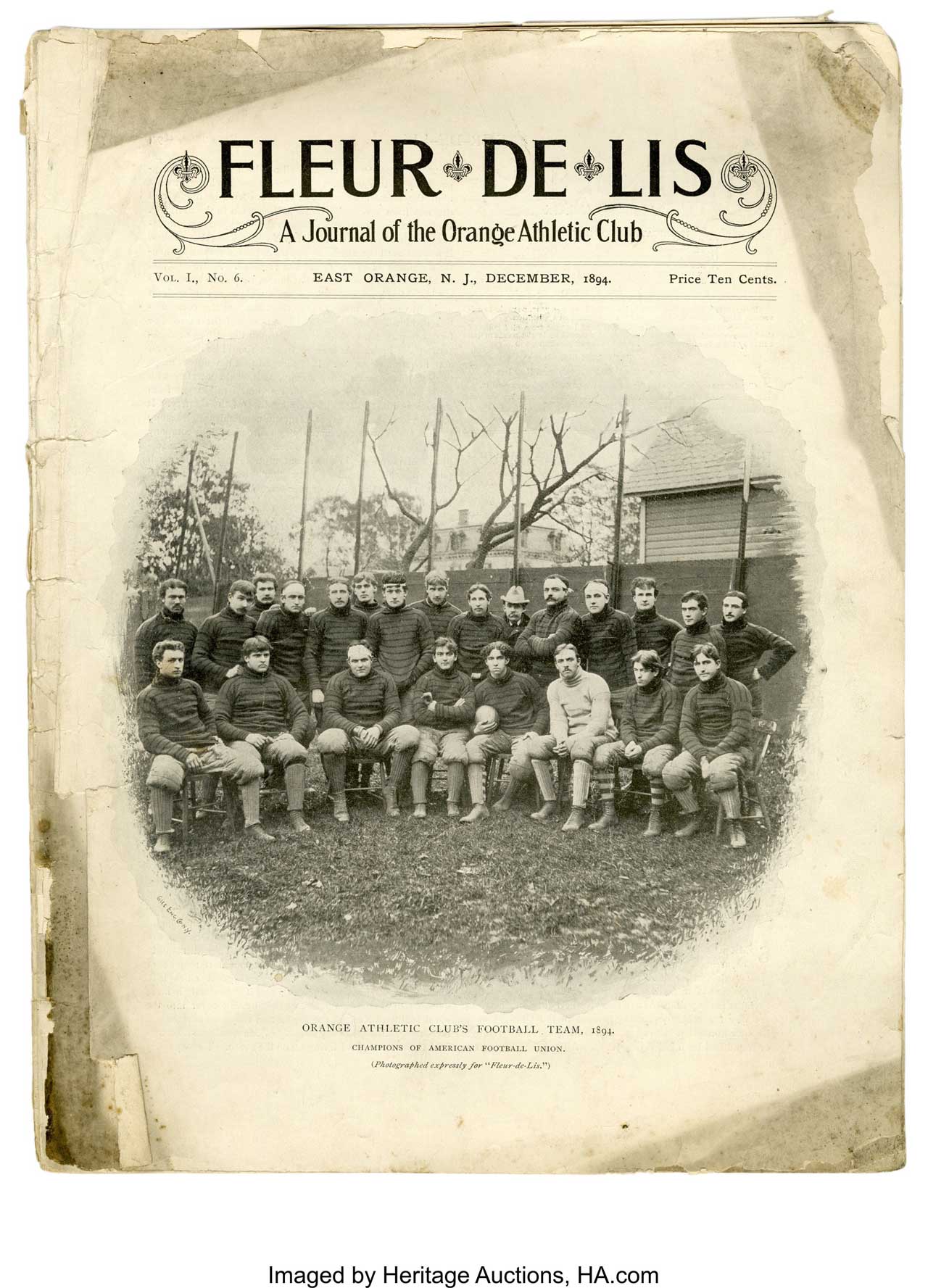

The sport back then was the bastard child of rugby and soccer. The field was mobbed with two 20-player teams who sported little more than turtlenecks. Moleskin headgear was introduced in 1896, but not required, and it took about a half-century longer for a coach to figure out that by attaching a face guard to the headgear, he could get more mileage out of an already injured player.

The game was high-impact, bloody, and fatal. Sportswriter Reid Forgrave, in his new biography Love, Zac about the late high school football player Zac Easter, traces the early years of the game, calling it: “A savage and unorganized game that was really little more than hazing for college freshmen.”

Scientists and researchers have spent the last half-century trying to prove that football deaths can be prevented. With better rules. With better equipment. With better practice standards. Computer programs like ImPACT can now detect concussions in kids as young as 12. But can technology ever advance to a point where risk is eliminated?

“In a high-contact sport, you’re never going to eliminate that risk completely,” said Jessica Springstead, the president-elect of the Athletics Trainers’ Society of New Jersey. “The basic mechanism of a concussion is the brain moving inside the skull. Understanding that can improve the manufacturer’s attempts, but you can’t eliminate the acceleration or deceleration.”

Springstead, who worked for seven years at a concussion center, says that rule changes are also necessary to prevent traumatic brain injuries. Among the proposed changes is to shorten the distance on kick returns to reduce the force of tackles.

Despite adjustments to the game, cutting-edge research, and two documentaries about chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) this year alone — one about Aaron Hernandez, another about Jim Tyrer — students continue to die for a multitude of reasons. Scotch Plain’s Evan Murray of a spleen injury. Neptune’s Braedon Bradforth of heatstroke. Two years ago, Dylan Thomas, a 16-year-old from Georgia, after an in-game hit, died of cardiac arrest. He was wearing all the latest equipment and both a county-certified trainer and orthopedic surgeon were on the sideline to assess his symptoms.

According to the National Center for Catastrophic Sport Injury Research, 42 football players died between 2015 and 2017. Of that total, 30 involved high school players. Perhaps what we must acknowledge is not the dangers of the sport, which we know to be true, but that it is a part of human nature to face these kinds of dangers. If there is something noble about playing through pain, maybe football is unfairly criticized. Why do we celebrate Curt Schilling’s bloody sock, Michael Jordan’s “flu game,” and Kerri Strug’s vault, but we say the death of young people like Zac Easter, who lied to trainers about his symptoms so that he could play, is evidence of football’s toxic culture?

Fortunately for football fans, the issue of whether the sport is brutal or toxic isn’t the concern of most critics.

“Adults can play whatever sports they want as long as they know the risks,” said Dr. Robert Cantu, medical director of the National Center for Catastrophic Sport Injury Research. “What I’m trying to do is to make sports safer — not to eliminate them.”

The real issue is consent. Can a child really understand the risks of developing a neurodegenerative disorder like CTE later in life? According to Cantu, who wrote the seminal book on youth concussions, the risk significantly increases the longer a person plays collision sports.

Playing less than four and a half years of tackle football, drastically reduces the risk of developing CTE, according to Cantu. “That’s why we don’t like people playing tackle football at an early age and starting that clock.”

Nevertheless, one national youth league, Pop Warner, is bucking the trend by introducing tackle football at an even younger age than before. Pop Warner’s website for its new pilot program called Rookie Tackle, touts risk reduction, but it doesn’t explain the logic behind that claim. In 2012, Pop Warner football was revived in Orange, but it’s not clear whether Rookie Tackle will continue past the pilot stage. Pop Warner acknowledged receiving a request from Jersey Digs for an interview but didn’t comment further.

Football isn’t just a game in the United States. It’s part of our culture. Getting parents and coaches to open up about the risks young people face is touchy. Forgrave, whose book challenges both fans and critics of football, said that the reason Easter’s parents were so forthcoming to him about the death of their son — who killed himself after suffering for years with CTE — is because Easter had given them a “charge.”

”This was his legacy,” Forgrave said. “This was his dying wish.”