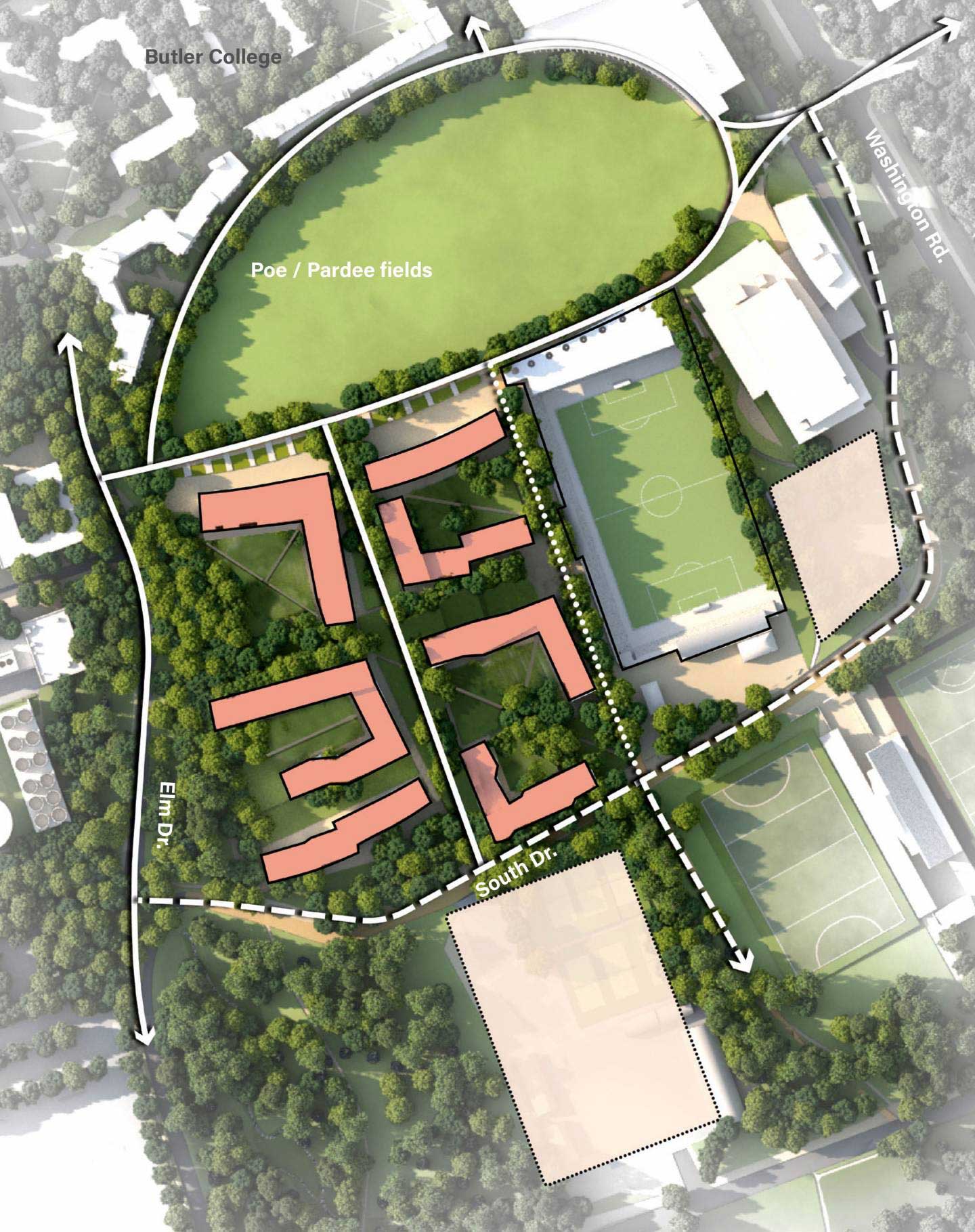

When we think of diversity and inclusion in higher education, things like curriculum, admissions criteria, and diversity officers come to mind. However, Princeton University is convinced that goal can be achieved through architecture as well. The key will be two new residential colleges — New College East and New College West — designed by Deborah Berke Partners that comprise eight buildings on the southern end of campus.

Residential colleges are an attempt to organize incoming students not by year, but by social clusters that include upperclassmen, faculty mentors, and advisers. All freshmen and sophomores are required to live in one of seven, soon to be eight, colleges. These new colleges will be a crucial part of the university’s ten-year plan to accommodate 10 percent more underclassmen and shed its blue-blood reputation.

“The purpose is not to admit 125 more alumni legacies that all went to Phillips Andover or Exeter,” said Atif Qadir, CEO of Hoboken real-estate consulting firm Redist, and host of the American Building podcast, which featured the new colleges on a recent episode. “This is particularly meant to admit first-generation, middle class, working class — all the people that can have the most transformational experience.”

Qadir, a South Asian immigrant, confessed on the episode that although he was admitted to Princeton as an undergraduate, he found the university’s staid Gothic architecture, surrounded by symbols of privilege, unwelcoming, and declined the offer. “Oftentimes it’s not the words that are important — it’s the physical objects that can count for a lot as well.”

The way Deborah Burke Partners sought to improve the first impression and experience of admitted students was to facilitate more impromptu social encounters with larger hallways, bump-outs, and open staircases. Another distinct feature of the new colleges is the use of large picture windows and transparent facades, a departure from the university’s traditional stone architecture that resembles a fortified castle.

“If you can’t see in, you can’t know what’s happening inside to know that you want to participate and be a part of that,” Arthi Krishnamoorthy, a partner at Deborah Berke Partners, said in the podcast episode. “We also designed spaces to be visible, to be interconnected, to have views out to the campus, so that you build an awareness of each other.”

College architecture has been a focus of the American Building podcast in its second season, which features Nick Falker, one of the developers behind a new residence hall near Yale University, and Paul Lewis, who designed an eight-story dorm for Carnegie Mellon. Qadir told Jersey Digs that higher-education institutions are taking advantage of low cost of capital and schools emptied out by the pandemic to undergo campus construction.

It’s a timely discussion as dormitory architecture has been under scrutiny ever since the University of California, Santa Barbara, released renderings for an 11-story residence hall, named Munger Hall after billionaire donor Charlie Munger. The memorable feature is that the rooms are windowless — a design so cruel that an architect quit in protest.

Among the issues the podcast’s feature architects have had to consider was the effect the pandemic — and the possible need for remote learning or quarantine in the future — would have on dormitory architecture. While the architects made certain adjustments to allow for the customization of rooms, Lewis didn’t think pandemic protocol was something that should factor permanently into designs.

“I’m hoping that’s not something we start designing for — I’d rather design for the more euphoric celebratory social reasons why we all exist in a society,” Lewis said. “Architecture should foster greater exchange, greater connection.”