Preservation New Jersey (PNJ) announced 2018’s 10 Most Endangered Historic Places and Jersey City’s St. Lucy’s Roman Catholic Complex made the annual list.

Founded in 1978, PNJ is a nonprofit that works to preserve sites of historical significance through raising awareness and advocacy. The public nominates historic sites and each year’s 10 places are selected based on three criteria: “historic significance and architectural integrity, the critical nature of the threat identified, and the likelihood that inclusion on the list will have a positive impact on efforts to protect the resource.”

Announced May 17 on the front steps of the State House in Trenton to honor National Preservation Month, “The act of listing these resources acknowledges their importance to the heritage of New Jersey and draws attention to the predicaments that endanger their survival…and aims to attract new perspectives and ideas to sites in desperate need of creative solutions,” says PNJ.

In Jersey City, St. Lucy’s is endangered due to its dwindling usage and its location downtown in the midst of frenzied real estate development. Established in 1884 in what was known as the Horseshoe section, the parish at 619 Grove Street served the influx of poor Irish immigrants at the turn of the 20th century. The complex is comprised of a school, church, and rectory, and is architecturally significant with Italianate and Romanesque Revival elements.

The church closed in the 1980s and only the school building remains in use as an emergency homeless shelter, with plans to relocate. Jersey City and the Archdiocese of Newark are discussing building a brand new facility across the street, leaving St. Lucy’s completely empty. PNJ is urging Jersey City and the Archdiocese to protect, preserve, and envision a new future for the 19th-century parish.

Usefulness and real estate development are just some of the challenges facing New Jersey’s most endangered historic places; neglect, lack of historic preservation funding, too few creative adaptive reuse proposals, and lack of recognition and protection by the government are challenges as well. According to PNJ, “This year’s list also includes several resources of not only historic significance, but that are also cultural landscapes representing New Jersey’s agrarian and water faring past.”

The risk to these historically significant sites is imminent — PNJ raises awareness and advocates tirelessly on behalf of these cultural resources and even suggests paths to preservation, but their protection is not a foregone conclusion.

The 2018 list also includes,

The Captain William Tyson House (Rochelle Park, Bergen County)

Built about 1863-1864, the Captain William Tyson House is one of the remaining grand Italianate houses of Bergen County. The Rochelle Park Township Committee wants to sell or tear down the house.

Hogan Farm (Westhampton, Burlington County)

A farmhouse and barn built around 1830 that is a perfect example of late 19th-century agricultural architecture with late Georgian and Federal details. Virtua Health System, who owns the land, wants to tear Hogan Farm down to make way for new medical buildings.

Homestead Farm at Oak Ridge (Clark and Edison Townships, Union and Middlesex Counties)

Established in 1720-1740, the farmhouse and 208 acres of open space offer an uninterrupted view of the Watchung Mountains. Homestead Farm’s farmhouse has sat unused for some time and Union County is planning to build athletic fields on the historic acreage.

Light Ship Barnegat (Camden, Camden County)

A steamship designed and built in 1904 by the New York Shipbuilding Company, it warned ships along the New Jersey coast of obstacles and shallow water. A private investor has owned the Light Ship Barnegat since the 1980s but has yet to assemble the resources needed for restoration.

First National Bank of Woodstown (Woodstown, Salem County)

Built in 1892, the Romanesque Revival building with Perth Amboy Pompeiian brick and red sandstone is a symbol of the new banking economy of the late 19th century. First National Bank of Woodstown is not in immediate danger, but it has been vacant since 2013, and PNJ hopes to spark interest.

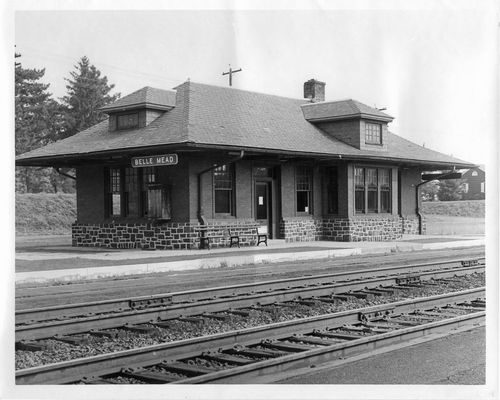

Belle Mead Station (Montgomery, Somerset County)

Built in 1913 along the West Trenton Line, buildings on both sides of the tracks are finished in red brick and detailed with chestnut trim. Service on the passenger line was canceled in 1982, but NJ Transit is studying the line with the thought of reactivating it. PNJ hopes the organizations involved will rehabilitate and find an adaptive reuse for the Belle Mead Station.

Mad Horse Creek Cabins (Lower Alloways Creek, Salem County)

It is unknown when the eight cabins, only accessible by boat, were built, but it’s assumed they date back to the 19th century. The DEP wants to demolish the Mad Horse Creek Cabins while simultaneously preserving the land, but PNJ and the surrounding counties are strongly urging otherwise.

Also on the 2018 list is a concern for patterned brickwork houses statewide and for the lack of funding for historic religious buildings specifically in Morris County and potentially statewide.

Jersey City’s own Apple Tree House, aka the Van Wagenen House, was listed on PNJ’s 10 Most Endangered Properties list in 1996 and just celebrated its grand opening last fall. It took more than 20 years, but Jersey City worked tirelessly to raise the funds necessary for a level of preservation and restoration deserving of a Historic Preservation Award, awarded by PNJ in 2017. The landmark is now a beautiful home for Jersey City’s cultural affairs and economic development offices.

“Although [the] list is published once per year, the fight for the preservation of our historic and cultural resources is daily, and the news of the Apple Tree House is evidence that bringing awareness of such threats can bring about creative solutions,” says Preservation New Jersey.