About a century ago, a small suburban hospital in Orange, New Jersey, became a sprawling, world-class medical facility funded by the era’s most famous philanthropists. But this landmark institution, listed on the National Register of Historic Places, had a tragic, mysterious ending. In this series, Jersey Digs tells the stories of those who worked, healed, and died here.

It all began as a pretty brick building in an old Italian neighborhood. Vintage photos of the original Orange Memorial Hospital show shutters and a wide wooden porch that gave it the look of a home. The hospital quickly outgrew that three-story center, blossoming into a six-acre medical facility with five of its nine buildings designed by a pre-eminent architecture firm.

The idea for a hospital and nursing school — one of the first such schools in the nation — came from Dr. William Pierson and socialite John Vose, who wanted to build it in memory of his late wife, hence the word memorial in its name.

Despite this personal dedication, this wasn’t merely a rich man’s vanity project. There was an urgent need for a hospital in the Oranges because the only ones in the county were miles away in Newark. Industry was leaving the city for suburban pastures, bringing with it a working class that found jobs at places like the F. Berg & Co. hat factory and Thomas Edison’s laboratories.

Broad avenues, railroads tracks, and trolley lines soon crisscrossed the countryside, turning tracts of dairy farms into thriving suburbs. With all this opportunity, however, came problems that plagued the 19th century: deadly epidemics and daily traffic accidents that necessitated a place to treat the poor, sick and injured.

Luckily, Vose moved in social circles with other local philanthropists, who also wanted to memorialize their loved ones. Several well-known captains of industry lived in nearby neighborhoods like Llewelyn Park and Seven Oaks, which had become fashionable addresses.

“This was an important event that families like the Edisons, Metcalfs, Sticklers, and Colgates put together money to build this hospital,” said Karen Jeffries-Wells, chair of the town’s historic preservation committee. “This is a major historic site and it’s right here in Orange.”

Even more personal dedications and historical artifacts were scattered throughout the buildings.

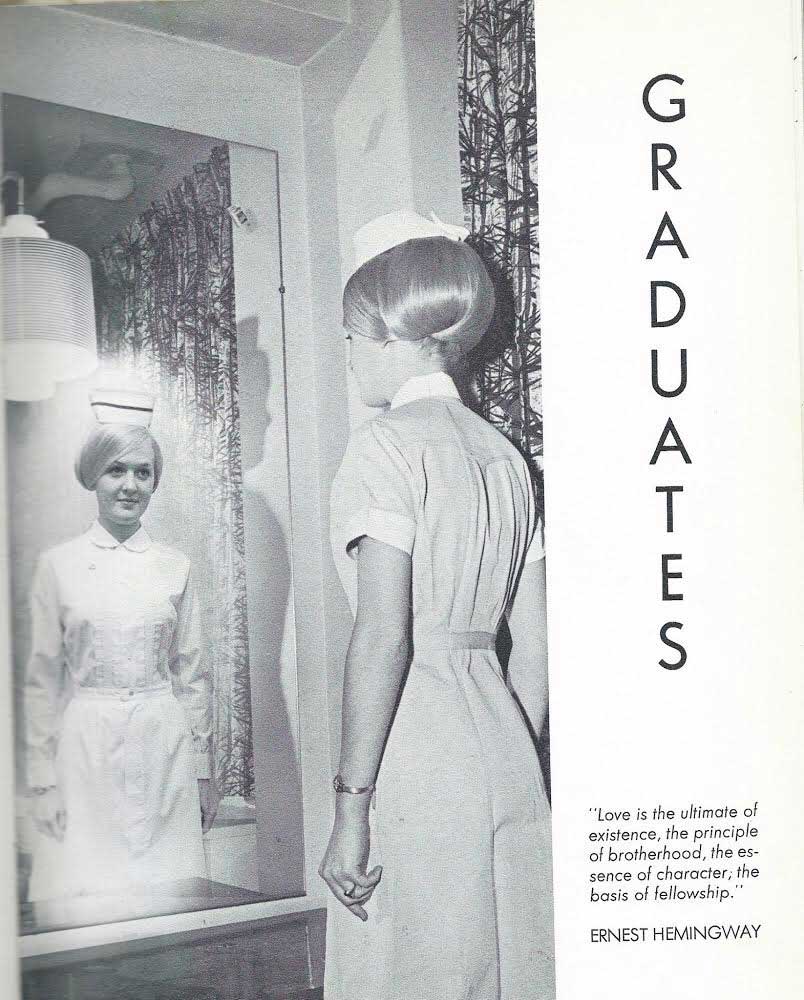

“We had an actual letter from Florence Nightingale hanging in the meeting room,” said Susan Lee, who remembers wearing blue seersuckers and regularly inspected knee-high dresses as a nursing student in the ‘70s. “It’s very sad to see the building so rundown.”

“Every door on every floor had a memoriam,” said Debbie Piserchio, who graduated from the hospital’s school of nursing in 1975, then served as head nurse until 1994.

Piserchio worked mostly in the maternity ward, but she was trained in orthopedics, a department she remembers as one of the most prestigious in the nation. “Children used to come from Europe to treat their scoliosis,” she remembers. “The patients used to be in body casts for the whole summer.”

Unfortunately, Orange Memorial Hospital suffered the fate of many hospitals in the early naughts.

“It’s an absolute tragedy,” Piserchio said, who remembers the hospital’s charitable spirit often spilled out into the streets with open-air clinics that treated the poor and uninsured, “and it’s something that never ever should have happened. It makes me heartsick.”

There are several theories why this landmark met such an unbefitting end. Health care advocates blame the debilitating cost of charity care for what was then an increasingly uninsured population. The Urban Institute, meanwhile, pointed to the repeal of so-called rate-setting laws, which were intended to limit hospital expenditures and eliminate price discrimination. Others even accuse Catholic Healthcare System, the company that saved the hospital from bankruptcy in 2002, of purposefully bleeding out Orange Memorial to benefit its other hospitals.

Whatever the case may be, the final years of this once-prestigious institution ended in sadness, anger, and shame. Talented doctors and nurses, who saw the writing in the wall, left for other hospitals, and the quality of care suffered. In 2002, the state health department shut down the hospital’s operating-room suite, citing health-code violations. The next year, hundreds of enraged workers protested outside the hospital, having been screwed out of their pensions. (The federal government eventually ensured the workers would received what they were owed.)

Over the course of these tumultuous years, the architectural integrity of these nine buildings has remained remarkably intact, which has made them a muse for historians and urban explorers. Five of the buildings were designed by famous New York architects Crow, Lewis, and Wick in the Colonial Revival style, known for its pleasing symmetry.

“The fact that the complex is still intact is unusual, especially because it’s been in relative use for so long,” said Logan Ferguson, who authored the 223-page application that won designation by the National Register of Historic Places. “A lot of the time you see major sections demolished or totally renovated so that they’re no longer recognizable.”

Even five years ago, when the landmark designation was awarded, the renovation of the complex would have been ambitious, said Ferguson, who works for Philadelphia-based firm Powers & Company.

Peeking through broken ground-floor windows, a passerby can see that the years have not been kind to the interior, where squatters now roam free through the nightmarish corridors. The ownership has since changed hands and the preservation commission admits it has not kept up to date with the property. The town said the property, which currently has a lien, is owned by Orange Flats, an LLC based in Brooklyn.

As for what the future holds, many fear that the developer may be running out the clock, letting time ravage the structure, and ultimately deem the property too dangerous to restore. Still, the preservation commission said it is “adamant” that the building not be torn down, assuring it would “unequivocally” deny any request to do so.

“No — not going to happen,” said Jeffries-Wells, who founded the commission seven years ago along with an attorney and the former chair of the local zoning board. “Over the years, I’ve seen too many historic buildings ignored or torn down, and this is not going to happen anymore.”

Related:

- Traffic Deaths Surged in the Early 20th Century, a Public Works Project to Prevent Them Will Soon Mark Its 100 Anniversary

- Preservation Commission Takes Final Stand to Save Historic Hospital in Orange

- Looking Back at Past Outbreaks as ‘Dark Winter’ Looms