Guest Post by R. Ballantine

Newarkers walk through the streets of a city whose buildings wish to be somewhere else. These buildings may not be apparent in the skyline, but they are obvious in their street presence. They shout to the sidewalk they don’t wish to be here. Bare walls of granite, concrete, and opaque glass shout “nothing to see”. These buildings insult our city’s inhabitants but are a comfort to commuters. These buildings are fortresses to suburbia’s denial that the route of their wealth was built on sidewalks that are now lifeless.

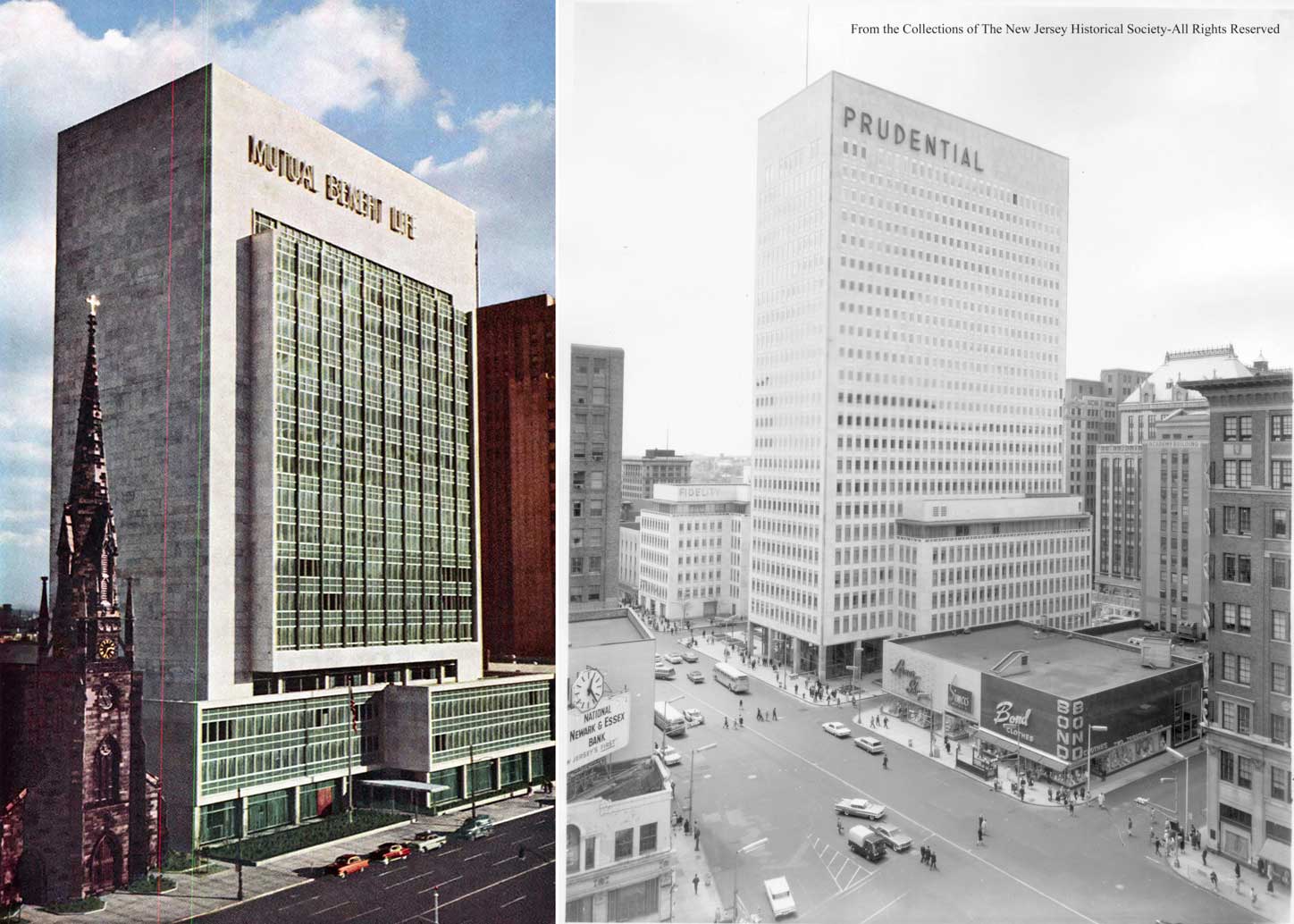

These buildings are the legacy of Newark after 1967, they stand in opposition to the modernist buildings of a decade earlier. When glass and steel represented a city breaking away from the shackles of tradition. Urban-Renewal brought great crimes to the treatment of the underprivileged of our city. But we cannot throw out the efforts of the many great designers and thinkers who believed that we could shape this city to be more egalitarian and technocratic. Walk around downtown and you see these mid-century icons: the original Prudential Tower, the IDT building, Colonnade Park… these were beacons of a city that wished to be up-to-date and with it. They hymned their rationalism, their adherence to technology, and the belief that light and air were tools of a society striving in the age of the push-button.

These buildings are striking but respecting of the pedestrian. Their mode of operation was that this new tomorrow was accessible and welcoming. Broad Street was the interface of a city electric with commerce and entertainment, and urban life did not end at 5:00 PM. One could escape the urban churn to the shining aluminum monoliths of the Pavilion and Colonnade. these buildings are not shy of their scale and bravura. They were seen as monuments of upward mobility, and in an act of forward-thinking, blessed with monumental trees that in summer cast gentle shades on sprawling lawns (no fences included).

And lastly, Rutgers Newark. Its Brutalist architecture cannot be accused of being offensive. Its butch forms are the antithesis of the architecture we see at Princeton and Harvard. Most college campuses, particularly the Ivy League ones, are sycophants of a notion that their buildings must evoke the styles of ancient academia found only in the old world. There is a rough nobility to the campus and its buildings, you move about its squares and quads, intermingling with the remnants of an older urban fabric. There is no clear separation of campus and city from the urbanist view. You can move from Halsey Street and up to MLK and the buildings are of a scale that doesn’t overwhelm you.

These buildings are lumped together with the post-riot era and are viewed by activists and preservationists with contempt. Urban renewal, they tell you, was a product of a society deeply rifted along class and racial lines. They fail to see that the city is under threat of the same stigmas that brought it to its decline. Residential towers built on podiums reserved for cars, retail spaces that will remain empty until the “right” tenant appears, office towers set back from the street with spiked gates and asphalt driveways.

We as citizens need to re-examine the legacy of our modernist and brutalist buildings before 1967, because they were built for a city and a mindset that looked forward. They spoke of an urbanity that was moving towards tomorrow, they were no match to the bigotry and backwardness of a populace moving to the suburbs and taking the city’s prosperity with it.