A senior-citizens facility that was a decade in the making, broke ground in East Orange last month and will provide 60 residents, facing ever more uncertain housing situations, a safety net of supportive services.

The timing of this development, located at 160 Halsted Street, couldn’t have been better. Cities like East Orange were already dealing with a critical shortage in senior housing. Applicants can languish for years on a waiting list of 908 residents for one of the city’s 244 units to become available

Meanwhile, even as Governor Phil Murphy’s moratorium on evictions extends to January, advocates are worried the pandemic could push aging residents to a dangerous precipice of housing instability.

“I hate to think of what’s happening to them,” said Elizabeth Davis, executive director of The Brookdale, a 62-unit senior living facility in Teaneck that has a waiting list of 700 applicants. “I’ve encountered older adults living in cars and couch surfing. It’s heartbreaking.”

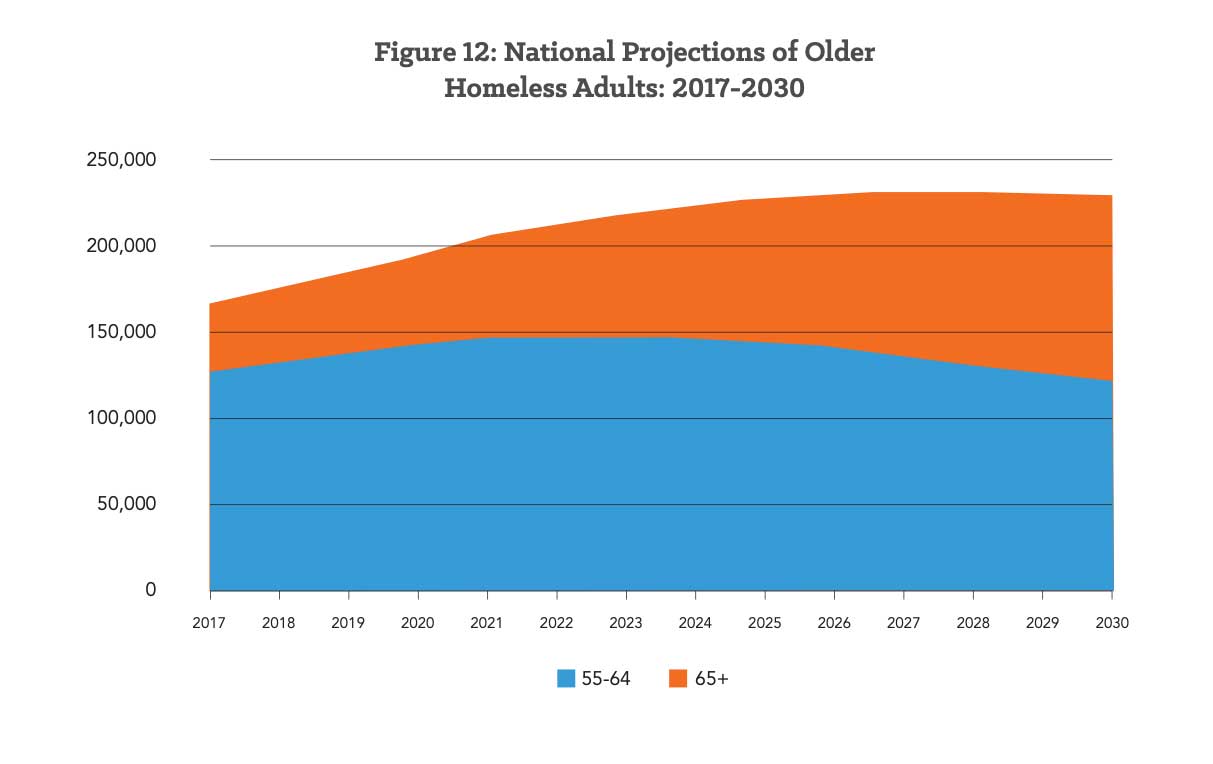

For decades, experts have been warning about a potential crisis sometimes called the “2030 problem,” which is the year when the number of Baby Boomers will reach 61 million. The combination of longer life expectancies, more chronic health problems, and rising costs of housing, pharmaceuticals, and medical care, has long fueled grave predictions.

The pandemic is only making the situation more imminent. A report commissioned last year by the National Council of State Housing Agencies revealed that 33 percent of individuals didn’t make enough to cover rent over a four-month period. And reports have emerged of landlords beginning to sue tenants for back payments.

These statistics tell a starker tale in places like East Orange, where three out of four residents are renters, according to census data, and nearly 20 percent of residents live below the poverty line.

“There is a big demand for affordable housing,” said Wilbert Gill, executive director of the East Orange Housing Authority (EOHA), “and an even higher demand for senior housing with supportive service.”

Financing, however, is notoriously difficult to stitch together and relies primarily on a state tax credit issued by the New Jersey Housing and Mortgage Finance Agency.

“The hard thing about the tax-credit program is that it’s very competitive,” said Gill, who said the idea for the Halsted facility preceded his nine-year tenure at the helm of the agency.

Hundreds of housing authorities and non-profits statewide vie for the same limited funds, which aren’t available each calendar year. The housing authority in East Orange was denied twice before finally winning an appeal, Gill said.

The rest of the funding for the $19.4 million senior residence came from sources like a $5 million HUD loan, as well as grants, including a $630,000 award from the Federal Home Loan Bank of New York.

Even though the EOHA already owned part of the lot where the Halsted facility is being built — it was formerly the agency’s administrative offices — the project still took a decade to realize. In the rare instances when funding for a senior facility is already secured — as in the case of The Brookdale — locals often protest senior housing, delaying projects or derailing them altogether.

“A lot of the towns don’t want senior housing — they feel it would cause too many problems, like unsavory people,” said Chris Hasselkus, a 70-year-old retiree who spent two harrowing years on the waiting list in Bergen County before finding a place at The Brookdale. “But it’s just a bunch of old people who don’t have the money to make ends meet.”

For seniors like Hasselkus, losing a job of nine years can lead to a snowball of misfortune: defaulting on his mortgage, declaring bankruptcy, and relying on the alms of family members. In desperation, he retired at the age of 62 to collect social security. But social security essentially penalizes the poor — seniors who retire before the age of 70, which many are forced to do, receive less each month.

“I wish these towns would wake up,” Hasselkus said. “This place saved me from disaster. I was really scared about what could happen.”

While the EOHA hopes to add 64 more units of senior housing after converting an existing public-housing building next year, at the rate senior housing is getting built, advocates are concerned how cities and towns can keep up with runaway demand. The number of elderly in the nation is expected to swell to 80 million in 2050, according to a study in Health Services Research.

“There is never a time when those units go unused,” said Nicole Lockett, managing director at Genesis Companies, the firm chosen to develop both the new Halsted residence, as well as Vista Villa, a nearby senior facility recently completed.

As market-rate rentals in East Orange continue to drive up prices, especially with glossy redevelopment projects in the pipeline, such as the Crossings at Brick Church, Lockett worries that the cost for seniors living on a fixed income is growing increasingly out of reach.

“And a lot of those market-rate rentals are substandard,” Lockett said. “It’s not going to be decent housing where people can lay their heads down peacefully.”