Fifteen years ago, Tom Mutascio, an electrician, was running wires through a crawl space in West Orange Town Hall, when he discovered a lost artifact. It was a box of old black-and-white photos of places in town. Hundreds of them. And they all had one thing in common — a strange serial number.

“Nobody knew at first what they were or why they were taken — but they were a treasure,” said Carol Selman, then a member of the local Historic Preservation Commission (HPC). “I’m good at looking at old photographs and teasing out information.”

The condition of the photos, their contents, along with a stroke of luck, made Selman realize that these were a rare set of “tax photos” funded by the Works Progress Administration (WPA).

Those who follow the news, like Selman, might have heard of WPA tax photos by now. Three years ago, New York City finished digitizing its collection — all 720,000 photos. Local historians dream of doing the same with the West Orange photos. But the collection remains in limbo, held by a former chair of the HPC. Jersey Digs reached out to this ex-commissioner for comment but never received a reply.

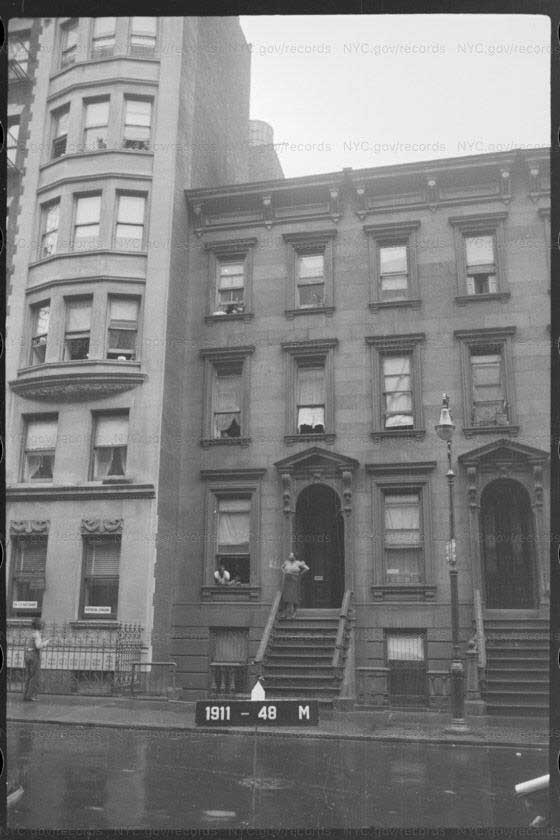

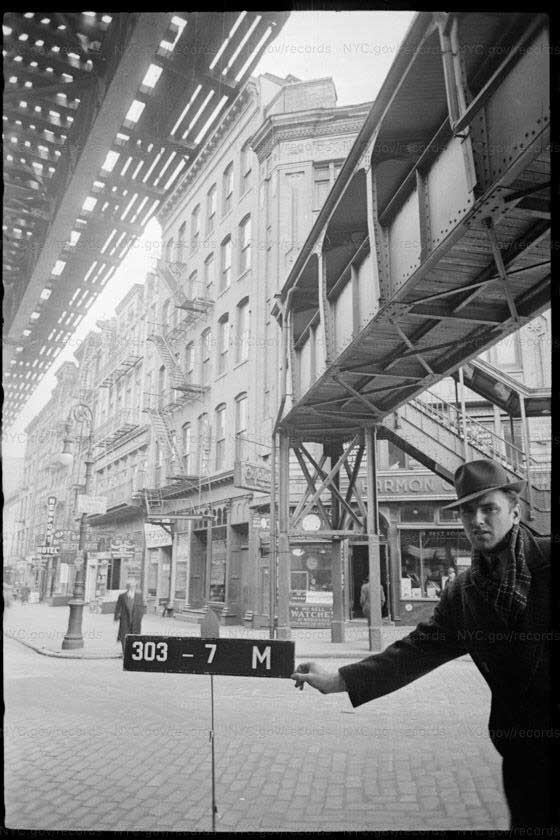

Before the 1980s, no one even knew tax photos existed, even in New York City, where the project originated. In 1939, the WPA — a federal program to create jobs during the Great Depression — sponsored a three-year survey for the city’s tax department. Two-person teams, comprised of a photographer and an assistant, snapped a photo of every property in all five boroughs for tax assessment purposes.

There were, it turns out, a handful of cities and towns across the United States that also participated. Similar surveys in places like Park City, Kansas City, and Seattle began to surface. The discovery of a collection in West Orange has kindled hope that other tax photos might be out there, somewhere, undiscovered in the basement of a municipal building.

The West Orange collection would be invaluable to the work of historic preservationists. After 1940, the country began a process of urban renewal in which many historic buildings were demolished or stripped of ornamentation. These WPA photos represent access to a lost world, which is crucial to restoration work and landmark designation.

“Anyone connected with the preservation of a historical structure or location would be happy to have whatever resources, written or graphic, to evaluate a property being considered as a local landmark,” said Marty Feitlowitz, vice chair of the HPC.

Aesthetically, many tax photos are boring or blemished and have little value beyond someone researching a home or family history. But some are poignant, capturing wisps of street life and candid portraits of people long-gone. One of the enduring mysteries is that these artworks were unsigned.

“Did these photographers go on to be famous? Or were they people randomly hired during the Depression?” said Ken Cobb, assistant commissioner at the NYC Department of Records & Information Services. “That’s a question we’ve been trying to answer for the past 40 years.”

Even though the photographers and their assistants sometimes made cameos in the tax photos, Cobb hasn’t been able to track down their identities, noting that the photos were discovered in the mid-1980s. “We started the research too late — by then, none of the photographers were left.”

Selman, who has since stepped down from the commission, used the New York tax photos to research her late aunt’s Victorian home. The former high school history teacher hopes that someday digitizing the West Orange tax photos will help others retrace their history and motivate residents to protect historic architecture with landmark designations. Llewellyn Park, listed on the National Register of Historic Places, is the town’s only historic district.

“We all die,” Selman said. “But buildings, if you care for them, have a life and a soul and stories to tell.”