About a century ago, a small suburban hospital in Orange, New Jersey, became a sprawling, world-class medical facility funded by the era’s most famous philanthropists. But this landmark institution, listed on the National Register of Historic Places, had a tragic, mysterious ending. In this series, Jersey Digs tells the stories of those who worked, healed, and died here.

In the late 19th century, traveling from place to place was a dangerous game. Trollies, trains, horses, bikes, and cars all scrambled on lawless roads. Newspapers ran daily stories of some hapless cadaver or amputee fighting for life in a hospital because of a traffic accident.

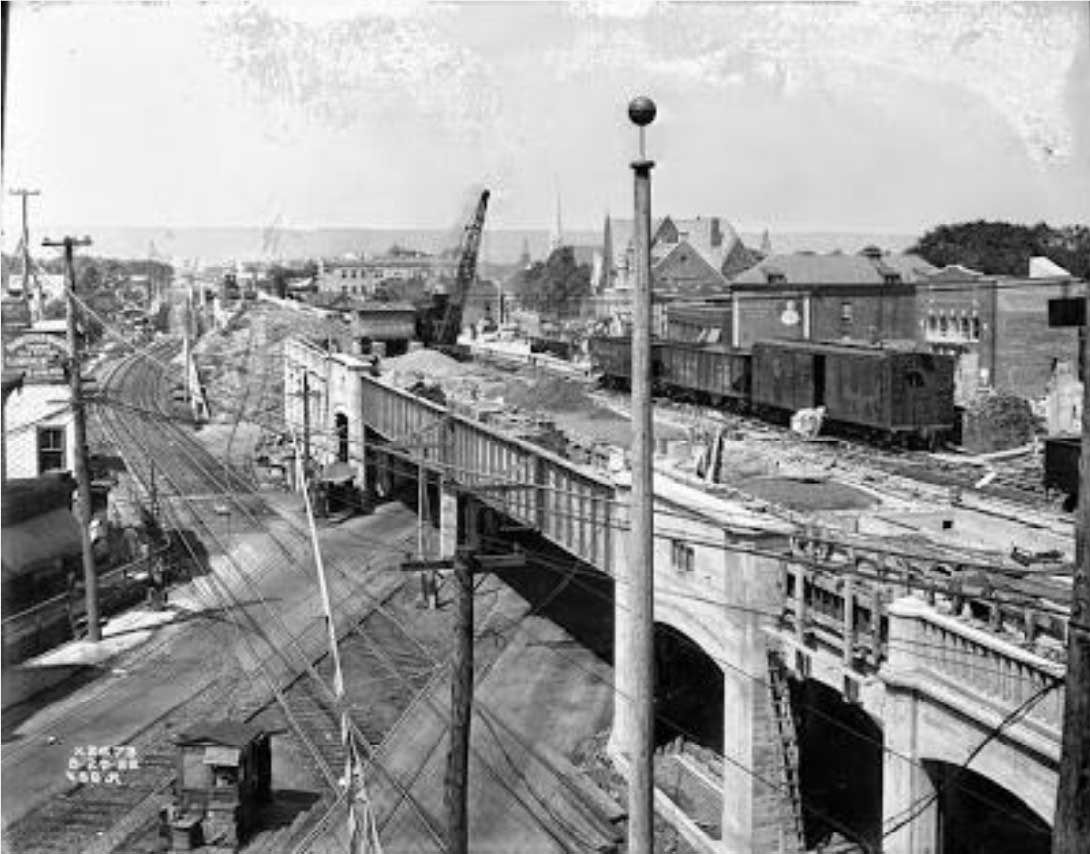

Perhaps the most important engineering feat of that era — in terms of improving public safety — was the elevation of train tracks. Over a three-mile stretch in Orange and East Orange, the Lackawanna Railroad eliminated 19 deadly grade crossings, which are places where street-level tracks cross over the roads. The yearlong project, completed in 1922, will soon mark a centennial.

It’s hard to imagine what traveling was like in the old days, given that cars these days are essentially computers on wheels that keep us not only safe, but also entertained. To get an idea, take a look at a vintage film reel of Newark’s Broad and Market Street, considered back then to be one of the busiest intersections in the world. You’ll notice without traffic lights, it was complete a free-for-all. In 1908, the city finally adopted the “one way at a time” principle at Market and Broad Street.

In 1910, East Orange introduced an elaborate system of sounds and gestures to control traffic flow: drivers would wave their hands to signal a stop and policemen blew their whistles either once to signal to a driver to slow down, or twice to stop.

Ordinances also forbade bikers from removing their hands from the handlebar or feet from the pedals. These strict rules were seen as necessary in response to news stories about slain locals that pulled at the public’s heart strings, like the one about William Mercadante. The 23-year-old Italian immigrant had left his wife and child back home in Italy so that he could get settled in the United States. Only two days before he was to be reunited with his family arriving by boat, Mercandante was struck by a vehicle while riding his bike and died at Orange Memorial Hospital.

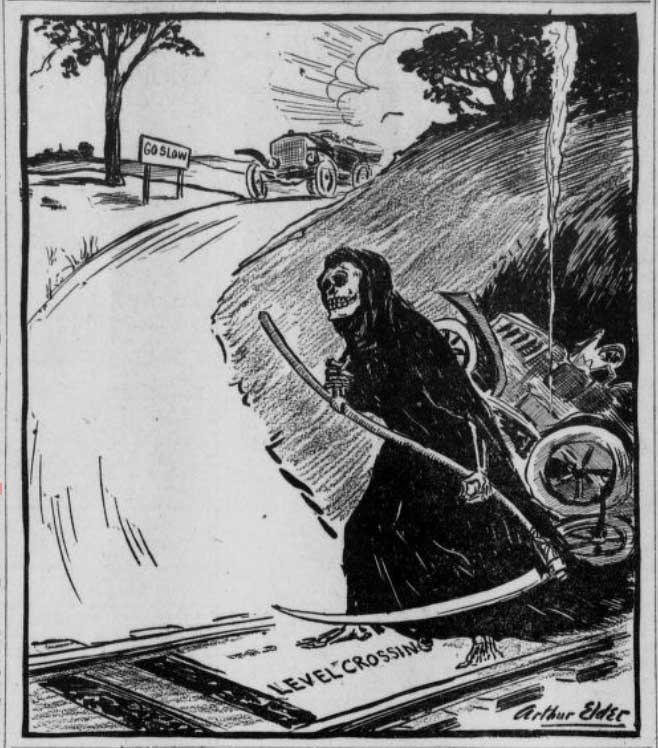

Meanwhile, deaths at grade crossings were like the school shootings of the early 1900s. Meaning that when one occurred there would inevitably be a flurry of news stories and political handwringing. But then nothing would happen.

Two news stories seemed to set the wheels in motion to finally address the problem. The public outcry came in 1912 when Newark Evening Star ran a front-page story about nine accidents happening in one day in which two died and 16 were hurt.

Then a few months later, two pedestrians died on the same day: Nellie Coleman at Hickory Street and Julius Harris at a grade crossing on Lincoln Avenue that was so dangerous, locals nicknamed it the “death curve.”

In 1913, Arthur Elder, cartoonist for the Newark Evening Star, drew a grim reaper waiting at the railroad crossing for an oncoming car. That same year, the Lackawanna Station tried to reach a deal with Orange to fix the tracks to prevent collisions, but local governments wanted the railroad company to pay for the elevation project completely.

“Orange shouldn’t be ask to pay a cent for the changes,” John Fineran, president of the Orange town council, told the Newark Evening News, “and it is a disgrace that the death crossings are allowed to remain to kill and maim our citizens because of a false notion of economy held by the wealthy railroad management.”

But the Lackawanna had already seen other townships agree to share the expense of fixing their grade crossings, like the one at Glenwood Avenue in Bloomfield, then considered the most dangerous crossing in the state.

It took nearly a decade for the project to break ground. The delay was not only caused by arguments over funding — which the Lackawanna finally agreed to foot the bill. There was also a debate among engineers over whether the railroad should cross under or over the road. Engineers eventually decided against an underground railroad because of the way groundwater flowed down from the nearby Watchung mountains that would have aggravated road and rail conditions.

At a cost of $4 million, the task of lifting three miles of tracks began. Carrying out the project without disrupting traffic and working through the winter was a considerable achievement at the time and was featured in the New York Times.

“At 5:26 o’clock this morning,” the New York Times story read, “a westbound passenger train on the Morris and Essex division of the Delaware, Lackawanna & Western Railroad will stop on the viaduct at the new Brick Church station in East Orange, thereby giving notice to the population of that city, which mostly sleeps in its peaceful precincts and toils in New York, of the practical completion of the work of elevating the railroad tracks on the Lackawanna system from Grove Street to Orange.”