Trenton is desperately trying to shed the reputation of its riverfront as a downtown dead zone.

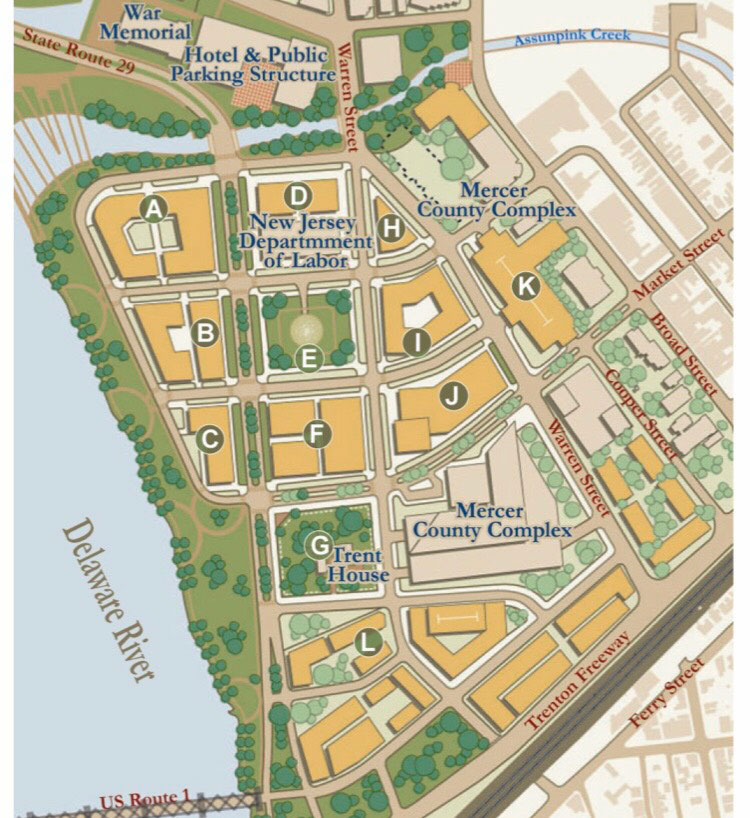

An ambitious redevelopment plan, called the Capital City Renaissance Plan, is attempting to reverse the legacy of mid-century urban renewal by reclaiming surface parking lots near Warren Street and relocating government departments elsewhere in the city. Left behind, however, are empty hulls of landmark modernist buildings that some fear are no longer part of the city’s future.

The demolition of two modernist buildings, designed by husband-and-wife duo Alfred and Jane West Clauss, have been the target of protests by city activists and historic preservationists who believe these structures mark an important evolution in International Style architecture.

“Nowhere else in Trenton do you find this late 1960’s style of office buildings which has graced the Trenton skyline for so long that few remember what preceded them,” said Karl Flesch, board member of the Trenton Historical Society.

The so-called Health & Agriculture Buildings, whose poured-concrete exteriors seem to dance in sunlight and shadow, were completed in the 1960s. These buildings, protesters argue, illustrate an important chapter of the city’s history and many would like to see an adaptive reuse project spare them.

“The most sustaining thing to do is not to destroy or build new, but to preserve these iconic looking buildings and put them to reuse,” Flesch said.

Both Alfred and Jane West Clauss were mentored by preeminent modernists of their time — German-born Alfred Clauss worked under Mies van der Rohe. Jane, an American, worked for Le Corbusier. After establishing themselves in Manhattan, they eventually opened a firm in Trenton, positioning themselves for commissions in both the capital and nearby Philadelphia, two cities that still bear the mark of their distinct architectural vision.

The mid-century era, when the Clausses were on the top of their game, was a time of unprecedented highway construction. The prevailing philosophy: create infrastructure that swiftly ushers commuters from downtown offices to their homes in the suburbs. It was in that era that Route 29 was built right along Trenton’s riverfront.

But contemporary city planners are trying to return to the city’s roots. The land where the Clauss-designed buildings stand was the former site of Stacey Park, a large green space remembered for its promenades and spiritual connection to the Delaware River.

The Renaissance Plan envisions a redesign of the highway so that the waterfront can once again belong to the public. Instead of a high-speed, elevated freeway, Route 29 would veer inland and become a tree-lined, street-level boulevard. But the New Jersey Economic Development Association admits that for an interim the demolished buildings will remain surface parking.

In 2017, the State Historic Preservation Office recommended that the Health & Agriculture Buildings be listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The designation never came to pass. Unfortunately, protesters are left with little legal recourse since losing a court battle last year. Now, protecting these landmark buildings must rely on a groundswell of opposition. Stakeholders-ACT!, a community organization, is holding a virtual event tomorrow in an effort to rally support.

“The demolition of two iconic buildings with no real plan for the vacated land,

beyond just more surface parking, will produce yet another act of racial and social injustice for the capital city’s residents,” said Shakira Abdul-Ali, a community activist and former city health director.